Qahr-e Melli

Post-revolutionary dereliction on stage

By Soma

March 9 2000

The Iranian

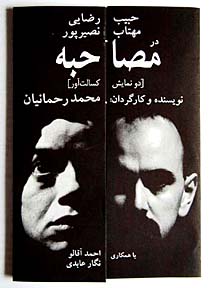

Mohammad Rahmanian has two plays currently on stage. The two appear

on intermittent nights in the same house -- Salon-e Chahar-su. Their subject

mater and mood are widely disparate, even though they share the same actress

(Mahtab Nassirpour) and actor (Habib Rezaii) on the lead.

According to the author, THE INTERVIEW was first conceived in 1985,

part of a television program. It was a history program intended on introducing

the audience to the Algerian revolution. Rahmanian had to research extensively

for the production. That included books by the renowned psychologist and

theoretician of the Algerian revolution, Franz Fanon. The studies led to

an interest in the fate of revolutions in general.

"It doesn't matter whether it is the French or Algerian revolution,"

Rahmanian says in an interview. "For me, as an Iranian who has had

the experience a revolution, the subject of a National Hero is a fascinating

one. As a writer, I am affected by the conditions of daily life and I must

bring these experiences in my works. It was as such that I wrote THE INTERVIEW."

He is, of course, too modest. THE INTERVIEW is not only the result of

his daily experiences with the revolution many people have been effected

by the revolution, even those with books to read -- but have hardly gone

on to produce scripts.

The made-for-TV program was never aired, and the director still doesn't

know why. It was first in the long line projects that was never to materialize

on stage or before the camera. Rahmanian did produce some plays for the

state television but they were all by foreign authors. For eleven years

he was not permitted to bring his own work before the public.

In 1993 he was permitted to stage one of his plays, TANBOUR NAVAZ, with

the single reservation that his name not be mentioned as the author. That

play was subsequently performed in the City Theater under the direction

of Hadi Marzban. But Rahmanian's name had to wait until late January 1997

when THE INTERVIEW was first staged as part of the annual Fajr Theater

Festival.

THE INTERVIEW: The Stage

On a circular, rotating platform, we first see a man (then a woman)

being asked questions by an intense streak of light coming from the director's

booth. There is no face behind the light, only a voice a man for

the man, a woman for the woman. The spectator immediately senses that this

is no ordinary interview, that it in fact borders on interrogation with

elements of a psychological investigation.

The setting is intentionally unobtrusive. No stage props, trappings,

or adornments to direct attention. A gray cloth hangs behind the interviewee,

separating each actor from the other and the audience. Costumes are plain:

white for the man, black for the woman. The actors are seated on a stool.

As such, their movements are contracted.

Rahmanian explains that when he was a student of the well-known theater

director, Hamid Samandarian, during one of the experimental performances

in his class, the teacher advised him not to hide as much behind the mise-en-scène.

It was then that the apprentice decided to confine himself to a play with

minimal movement.

The Story

The story is unclear its temporal progression erratic. The only

Time is that of the spectator, who, as the play progresses, comes to a

slow but a skeletal understanding of the unfolding plot. The plot is heavily

political, the subject matter one that was prevalent in the post-colonial

world of the mid-twentieth century.

Having seen and read Third World liberation movies and books of the

sixties and seventies, the audience may find familiar ground. Psychology

is an intrinsic part of the story's basic structure. The two characters

can only be understood via their profile: who they were, how society regarded

them, what they did, and where they end up.

Rahmanian maintains that THE INTERVIEW is the actor's play (and not

the director's). That the play was written without any recourse to stage

directions certainly bear's this fact. It also points to its modernist

heritage: the actors must put themselves in similar psychological states

of mind before they can inhabit the world of the characters.

Besides the stage that they share, there are only two circumstances

that draw a similarity between the protagonists: the crime that they commit,

and the derangement that they find themselves in. But a mechanism is at

work here: evasion. Any "interview" immediately gives way to

a state in which the interviewee evades a straightforward answer. "Every

interrogation is also an 'interview'," proclaims the author. "Anyone

who tries to uncover a concealment, in fact enters into this game."

The minimalist staging, the concentration on text, the singular beam

of light, and the one-dimensionality of characters has allowed Rahmanian

to masterfully bring out this facet of the play. The spectator is riveted

by the dementia that commands the gestures of the actors, the intensity

with which they are escaping their act. But the act that they are fleeing

is one that is conditioned by an infinite number of elements. The characters

are there to represent not the glory of the revolution, which produces

National Heroes, but its downfall once the feast is over.

"For me the subject of national dereliction (qahr-e melli) is a

fascinating one," says Rahmanian. "The two characters are leftovers

of national dereliction, residues of a society that doesn't need them anymore,

even while they fought for that society at some point." A post-revolutionary

society that strives to regain normalcy, that tries to establish itself

not as an ever-changing nation but one that can perpetuate stability, produces

such fallen heroes.

But THE INTERVIEW is more than a political statement. The author/director

has been able to find a dramatic language and tempo that can bolt the spectator

to her seat, despite the fact that her ears are already replete with the

subject matter (revolution, war, terror, and mania). The author maintains

that the language of the play is not dramatic - "as we expect"

it to be - but journalistic; that he has tried to bring an everyday

language to stage. But he goes on to point out that the drama lies in the

unfolding plot.

Hamid Amjad, another promising playwright who over the past two years

has succeeded in staging three of his plays (ZARVAN, NILOOFAR ABI, and

PASTOO KHANEH) to wide acclaim, comments on Rahmanian's play:

"In a proper dramatic dialogue, the character doesn't reveal her

internal propensities. No character can mouth her desires completely, because

the structure of the play inheres an obstacle along her path. A character

that has no desire; or does have a stumbling block before her, is not a

dramatic personage, and has no visual appeal Every dramatic dialogue, in

one way or another, is a camouflage to hide the internal desires of the

character, and not a mouthpiece for their exposure."

Amjad considers THE INTERVIEW an exquisite example of dramatic dialogue,

because it is able not necessarily to shine light on the inner thoughts

of the bruised mind of two young Algerians, but to establish a relationship

between the dramatic personage and the spectator: "The characters

try to evade and hide themselves, and our mind goes into gear to bring

an order into the scattered world that has befallen them."

Eventually, Amjad believes, the spectator succeeds and order is brought

into the theater. The spectator becomes accessory to the investigation

taking place on the stage. The spectator helps the beaming light to string

together the scattered mental elocutions emanating from the deranged minds

of the character, and reveal the hidden circumstances that led to the crime.

But it is precisely this order that is the death knell of the characters.

Once their secret is revealed, they become condemned personas in a world

where there is no room left for them. The spectator who has outlived the

perils of revolution and war soon discovers that his very existence is

a threat to the lives of the stage characters.

***

Despite its passé subject matter and the fact that it has been

written more than fifteen years ago, THE INTERVIEW is an testament to the

country's current predicaments. Iranian movie directors have tried to shed

light on the situation of those who, having given their youth and passions

to the cause of revolution and war, are left out in the cold by the new

generation and circumstances that have emerged. But THE INTERVIEW has succeeded

to bring the spectator into the equation, not as one who sympathizes with

the characters, but as one who can sense the providential situation that

they find themselves in.

As the modernizing drive of the new administration pushes forth, and

as a new generation speedily occupies the centers of power in the Islamic

Republic, it is important to realize that many of those left behind in

the race to normalcy will not be as readily identifiable as Safieh (the

lead character) and Na'im. Many will try to derail the process that has

already been set into motion by appealing to extreme measures that may

be characterized as terroristic. But the fact remains that the mechanism

of evasion that the play attempts to bring out will be outstanding not

only under the beaming gaze of the spectator in the theater but in the

world that is occupied by the downtrodden.

![]()