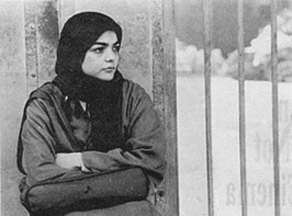

Scene from The Circle, winner of the top prize at the

Venice film festival, 2000. News here

No more kids stuff

"The Circle" tackles women's issues without pseudo-poetic

symbolism

By Roya Hakakian

September 29, 2000

The Iranian

At long last a film we can be unequivocally proud of. No more prefacing our apologetic

reviews by, "well given the circumstances under which the director had to work."

Gone are the days of kids, vague Sufi messages or innocuous village people. Time

for some serious hardy subjects. Time for The Circle.

The Circle is the boldest film to come out of the Iran of the Ayatollahs.

With no pretense or resort to the quintessential Iranian hide and seek techniques,

pseudo-poetic symbolism and metaphors, The Circle really says what is on its

mind.

It takes on one of the most hard-to-handle issues of our time: women. Over the

past twenty years, so many Iranian directors have tried to tackle this subject. Some

filmmakers have have created virtually "women free" screenplays. Well-intentioned

others, too overpowered by the charged nature of their subject, have produced pictures

that amount to no more than weak and predictable propaganda. If they have won over

the audiences, it is probably more by way of guilt than through the viewer's surrender

to a cinematic experience.

But all that belongs to the pre-Circle era.

Now comes a landmark film that sets out to simply tell a good story. In executing

its creative agenda, The Circle effortlessly and elegantly delves into one

of the most taboo subjects of contemporary Iranian society. Jafar Panahi's latest

film follows a very focused and clear vision that is evident the moment it starts.

The opening credits roll over the sound of a painful child delivery. The howling

of the mother ends on the director's name and the appearance of the film's most important

image.

Contrary to its name, the film opens on a rectangular portal and the battle lines

are drawn right there and then: an angelic white figure announces the birth of a

child. A shrouded black figure mourns the delivery of something other than a boy.

Logically, the viewer prepares for the tale of the mother who has just delivered

the wrong baby and the fate of her unfortunate child. But instead, Panahi's probing

lens finds three girls just outside of the hospital who are on the brink of getting

arrested. The next few minutes take the viewer on the quest of the two girls to buy

tickets to a paradise that one claims to be even more perfect than Van Gogh's paintings.

Along with the portrayal of the girl's dark and desperate mission, there is life

with all its lures. The film is lush with melancholic music, the hustle and bustle

of the bazaars and handsome flirtatious boys whom the girls do not let pass unnoticed

in spite of their troubles. And all this is told without wielding the pedantic preachings

customary in Iranian films. Most of the film is conveyed in images with a very few

lines of easy dialogue.

Soon, the film leaves the two girls behind and shifts to yet another girl who

flees the wrath of a violent brother and bursts out of her father's home onto the

screen. For a few moments, it is unsettling to abandon the two previous characters

who manage to be highly real. But the broader story is larger and more unified than

the sum of the smaller individual tales.

One character leads to the next until they all come together in a poignant fruition

in the last character: the first unapologetic and sympathetically portrayed prostitute

in Iranian post-revolutionary cinema. She is voluptuous and "cool" with

an unyielding tongue and a passion for cigarettes whose bright red lipstick alone

lights the screen with a long overdue and welcome fire. And yes, beware of a devastatingly

tragic ending.

Though even the quality of this tragedy is uniquely different from its other Iranian

counterparts. It is in keeping with the film's no-nonsense attitude.

Uncharacteristic of its own tradition, there is little vagueness and great clarity

in how the picture ends and what becomes of all the women caught in the vicious cycle

of The Circle. While the film is unmistakably Iranian, the tale of these women

is undoubtedly the universal story of women's plight for an equal share in an unequal

society.

![]()