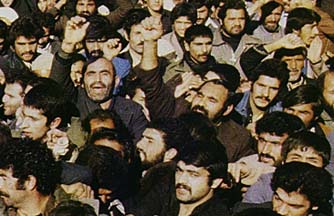

Photo by Hatami

Fiction

In front of the Embassy

By Massud Alemi

May 14, 1998

The Iranian

In the middle of a crowd, unusually thick for a Tuesday, Mike and I are walking toward the embassy. We want to know what's really happening. It's bright and chilly. The schools are closed, the bazaar shut down. The sidewalk is so crowded the swarm of people spills into the street, stopping traffic for three blocks in each direction. Pedestrians can walk without fearing the obnoxious cab drivers who drive their orange Paykans as if they own the streets. Big showoffs, Tehrani cabbies.

The crowd becomes thicker as we advance; it grows into a solid mass of flesh in front of the gate of the now occupied embassy. A small mob, there to hype the event by shouting slogans and cheering people on, is being filmed by the fascinated crew of an international broadcasting company. Street vendors have set up their decorated stands everywhere. One stand carries a mountain of steaming red beets. Farther on, a kebab vendor enthusiastically fans glowing charcoal.

Mike is American. We met at an anti-Shah demonstration in Washington DC, where it took me by surprise to hear him speak Farsi. We soon became roommates, renting an apartment in Falls Church, Virginia. Like all couples, we have our share of incompatibilities. For one thing, he is a public person, where I am more private. He doesn't understand why I don't want him to be open about our relationship; I don't understand his constant need for approval.

When I decided to visit my parents in Tehran, I thought I'd go alone, so as not to have to make up stories, to lie. But Mike wanted to know my family, see the town where I grew up, all that romantic stuff. He also said he wanted to see the revolution firsthand. "How often does one get a chance like this?" So here we are in Tehran, staying with my parents. They like talking with him in Farsi. But I wasn't wrong -- the whole thing is a headache. Apart from our first day here, I've had no peace. Mike doesn't understand where my parents come from. If his carelessness gives us away, if they find out about the nature of our relationship, they will be more than heartbroken. So far, they don't have a clue. But the tension is too much; Mike and I fight. I blame it on him, he blames it on the dry weather. We fought last night. Now we hardly speak.

Being here in front of the embassy isn't such a great idea. It wasn't mine. I tell him so. "Cool it," he says, and looks up and down, "I can't see shit from here." He insists we go closer. I follow, not wanting to leave him alone the way he is, all wired up, chain-smoking. Back in the States, it would have taken us days, maybe a whole week, before either one of us spoke. Now, we have to. Children of all ages are running around with their coats open even though it's freezing cold. People silently walk along the cement blocks that protect "our beloved students." Men talk to each other, but not for long. Their short, lethargic whispers convey more emotions than a regular conversation.

In the meantime, the cameras are rolling. They make sweeping moves from one end of the crowd to the other. By now the mob has inched its way to the gate. The voices of the observers-turned-demonstrators become louder. There are two cameras. A shoulder-held one carried by a bulky guy who keeps combing his long, red hair with his free hand, securing it behind his ear, and a larger one fixed on a roller-tripod. Because of its size, this one is taken more seriously by the demonstrators. Whenever it faces them, they raise their fists and shout angry slogans. The moment it turns the other way, they drop their fists, and light a cigarette or continue their conversation. As soon as the camera swings back, the fists go up again.

An old woman in a chador comes toward us, and pulls at Mike's sleeve.

"Where are you from, Blue Eyes?" She asks with an inquisitive smile, showing her brown, toothless gums. Mike is taken aback. I can see his chest heave. But I have to hand it to him, he's in control of his voice when he answers her. "Let's see if you can guess, Nanjoun," he says. The old woman, who sports a graying mustache, takes up the challenge. "Germany?" she says. Mike's head moves slowly to the left, then to the right.

"Until the death of the traitor Shah," the demonstrators chant, "the struggle will continue." The old woman is persistent. "France?" she asks again, and again Mike's head moves left and right. I feel a strong pinch in my chest. The voices in the background shout slogans more vigorously. "England? Russia?" She pauses, but I can tell from her stern, witless gaze that she will not give up. I imagine she's run out of names; her world contains only a handful of countries. There's one that she hasn't mentioned yet. I pray she won't remember it.

"Come on, man," I say to Mike, "let's get the hell out of here." He's crazy, and I am too if I think he will listen to me. For there's a certain look of amusement in his face that scares me. "Crazy American," I say to myself, and turn to the woman. Her eyes sparkle. She has remembered another country. "A. . . America?" she asks. Mike stands still. I expect the world to break loose at once, the whole universe to come tumbling down. But nothing happens.

A handful of teenage boys gather around us. There must be six or seven of them. One is eating beets from a crumpled newspaper, another is picking his nose intently and staring at Mike. Mike smiles at them, and lights a Camel. Only I can detect the slight tremor of his hand. "Don't be afraid of us," the old woman comes again, shaking her head, "we don't mean harm." The boy with the beets holds out his hand. Mike takes a couple of slices and eats them while the old chadori woman lectures him. "We don't hate you," she says, "we hate your government." She goes on about the "American people" and how they should know what she's angry at. Every now and then, her tongue crawls out of her toothless mouth and wets her lips. She talks with the self-assurance of a public official talking to her American counterpart. I feel like laughing, but Mike is listening intently. The exchange attracts quite an audience. The scene is much bigger than I'm prepared for, but I stand there and take it all in. A man reaches out and shakes Mike's hand. The shouting and chanting, reserved for international broadcasting, has ceased. An old villager touches Mike's clothes as if to make sure that he's real. A real American. What a sight!

Related links

* Also by Massud Alemi

* Reflections

about my hero

* Arts & Literature

* Cover stories

* Who's

who

* Bookstore

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved. May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.