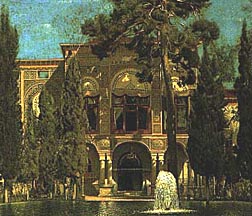

Golestan Palace by Kamal

ol Molk

Commotion

Novel

February 22, 2001

The Iranian

From The

Persian Bride (Houghton Mifflin, 2000) by James Buchan. Hailed as

a masterpiece in Britain, where it was first published under the title

A Good Place to Die, the novel is the story of a young Englishman,

John Pitt, who comes to Isfahan in the early 1970s and falls helplessly

in love with one of his pupils, Shirin Farameh. The lovers run away to

a deserted house in Bushehr on the Persian Gulf coast, but in the chaos

of the last years of the Shah, they are separated. This is the second extract

to appear in The Iranian. See first extract

From The

Persian Bride (Houghton Mifflin, 2000) by James Buchan. Hailed as

a masterpiece in Britain, where it was first published under the title

A Good Place to Die, the novel is the story of a young Englishman,

John Pitt, who comes to Isfahan in the early 1970s and falls helplessly

in love with one of his pupils, Shirin Farameh. The lovers run away to

a deserted house in Bushehr on the Persian Gulf coast, but in the chaos

of the last years of the Shah, they are separated. This is the second extract

to appear in The Iranian. See first extract

For years now, I have sought to feel again the sensation I felt, if

only for a moment, one day during the Iranian Revolution. It was 5 November,

1978, the day they burned the banks in Tehran and paper money fluttered

here and there in the hot draughts above Ferdowsi Square. The sun was dissolving

in dirt and smoke as I set off, going nowhere in particular, except downhill,

under the force of my own gravity. I knew I must be off the street because

of the curfew. I came into Lalehzar and the reek of alcohol made me swoon.

Beneath a scorched movie poster, under the colossal bare pink legs of

a trunkless woman, the beer bars had been sacked, their window grilles

twisted as if by giants and tossed into the street. I crept down the hot

tarmac, through drifts of broken bottles and window glass, and aluminum

beer cans fused into sheets by the fire, where the chance sight of a bottle

still upright with a mouthful of vodka in it set me to maudlin reminiscence:

Drunk beyond all reason once

Nasser Khosrow took a walk outside town

And passed a dung heap and a cemetery...

There was nobody about, because of the curfew, except sometimes I glanced

through a sidestreet and saw a troop carrier plunge northward between the

dark cliffs of office buildings.

I walked on downhill. In beautiful Tehran, to walk downhill is to descend

into past times. The streets were warm and dusty and quiet and smelled

of horses, and after a while I knew I'd reached the nineteenth century.

I thought if I walked on I'd see Amin ul Mulk prance by on his grey and

the flash of the cannons he'd brought back from Moscow to call the hours

in Ramadan and the ladies passing in curtained second-hand kalashkehs and

tulips and patched dervishes and heretics hanging from the gibbet in Artillery

Square.

I found that I could not walk straight and that I was drunk on air.

Before me were iron gates. I pushed and they opened on a breeze that

cooled my cheeks. The moonlight flashed and sparkled in little canals that

criss-crossed the garden, lulling and soothing. A soldier with a rose in

his teeth and a breast-pocket bursting with banknotes appeared, smiling,

before me.

He scampered over the canals in plastic sandals, his rifle butt catching

in the box hedges. We were moving towards a rickety building that scattered

the moonlight from a million stalactite mirrors. Before it was a stone

staircase guarded by stone lions and an alabaster frieze of soldiers with

embroidered skirts and European muskets and stiff moustaches. I turned

to thank the boy, but he wasn't there. The moon rattled in the branches

of a weeping mulberry.

I lay down on the cut grass, and as I lay down, I felt I'd fallen out

of my century; and falling, left behind the blazing liquor stores and swirling

banknotes, the heat on my face and the clatter of helicopters and the women

shrieking in black georgette and the shield round my neck that read I AM

IN SEARCH OF NEWS OF MY FAMILY; left cities behind and events and certainties;

and in my solitude and shame found my way out of the world:

Sweet mamzil moon

Hiding in branches

Or bathing in a far-away canal.

Too late!

Sleep scatters me with this year's leaves.

***

I staggered up. The sun scalded my face. On the pavement before the

mirrored porch of the palace, in a space made by tended rose bushes, three

well-dressed men were walking away from me. A fourth stood at a distance

of about fifty paces, holding a clipboard and an open fountain pen. Further

away still, a high military officer stood rigidly to attention.

The three turned; or rather the man in the centre turned, and the men

on each side skipped a step to turn with him. All were tall, but I was

surprised that the men on the outside were foreigners, Europeans or Americans.

The man on the left as I looked at the group, whom I recognised as Burchill,

the British Ambassador, was speaking softly, rapidly, with his head down,

not just out of respect but perhaps for fear of a reaction to his words.

The man on the right, who was no doubt the United States Ambassador, Freeling,

looked straight ahead as if not fully a part of what his colleague had

to say; as if, indeed, his mind were in America.

Between them, the Light of the Aryans looked baffled. His handsome face,

his gleaming hair, his well-cut suit, his patience and courtesy seemed

to have been abandoned by his troubled spirit. I saw that he was wrestling

with what Mr Burchill was saying so quickly and quietly or rather with

a conception that was new to him which was this: that he did not trust

the man, or the other, or their governments, which meant he did not trust

anybody. A pair of hooded crows flapped and fought on the pitched roof,

plebeianly.

We stagger up.

The sun is high.

Delegations hurry by.

I stood up. Had I stayed where I was and been seen, I would have been

shot. In reality, I stood up because I was drunk on air and because I did

not think it right to eavesdrop on other people's affairs. The Shah shivered.

It was not simply that he had been here before, I can't remember when,

but as a young man, when a boy put five bullets in him in the garden of

Tehran University and he survived and thought himself under the protection

of Lord Ali himself. There was something about my wildness, and my strangeness,

that suited the drift of his thinking, as if his very suspicion of the

ambassadors had materialised me. He turned on Burchill in savagery. Burchill

sprang in front of him, not so much to shield the Shah from a bullet as

himself from suspicion. Freeling woke from his reverie, reached to his

lapels for a weapon, thought better of it, made as if to push the Shah

to the ground and thought better of that, too: as if some aura of God's

Anointed still radiated from the person of the Shah. The general was running

at me, tugging at his side-arm as if it were a snake with its teeth in

him. The official with the clipboard was stepping towards me on brilliant

hand-made shoes.

I put out my arms to show I had no weapon. I smiled at the Shahinshah.

He blinked at the presumption, then relaxed.

"Disarm the boy," he said.

"It will be obeyed!"

The garden burst into life. The tin roofs bristled with riflemen. I

could see the General running at me was going to shoot me, just to be on

the safe side, and then the other fellows would turn me into a colander,

to earn their pay and expenses and at least to shoot somebody. I turned

my back to them and rested my cheek against the hot mulberry bark. That

was cowardice, but in those days I believed people had a compunction about

shooting in the back.

"Who sent you? Where is your accomplice? Where did you drop your

weapon?"

The official was standing very close to me, shouting so all could hear.

His breath on my cheek was putrid, as if he were ill. I sensed he was fastidious,

and anyway needed to conceal his illness, and stood so close to me only

to keep me from being shot.

I whispered: "I had business with you, Excellency." And then,

because the Immortals were all around me, peering down their automatic

weapons, a hair's breadth from riddling me, I laughed and said: "'A

dervish came into the presence of the Sultan and began to make a commotion.'"

Which, as every Iranian knows, is a story from The Rose Garden of

Sa'adi.

Purchase this

book

![]()