From the cover of "Tales of Two Cities"

December 1996

The IranianFrom "Tales of Two Cities: A Persian Memoir" (1996 Mage Publishers, Washington, DC, $29.95) by Abbas Milani. The book was on the San Francisco Chronicle's Best Seller's List in early 1996. (Reviews)

(pages 21-23)

I was born in Tehran in 1948. I was seven before I ever heard of a birthday party and learned that the day and the month of birth are as important as the year. It took another decade and a trip across the world before I understood that for some people even the precise moment of birth, down to the seconds, and the corresponding constellation of heavenly bodies, is important. In my childhood, however, the only significant fact about our birth was the year - and that only to determine when we should go to school or be drafted into the army.

Once an ignoble village, pastoral and mountainous, Tehran is near the ruins of the historic city of Rey. Around the turn of the century, when the inhabitants of Tehran were ordered to stay home for forty-eight hours so that the first census could be taken, the population of the capital had already surpassed two hundred thousand. By 1948, one and a half million people lived in a city then caught in the jubilee and confusion of a short-lived post-war democracy.

When in 1975, after an absence of eleven years, I returned to the city of my childhood, it had swollen into an overcrowded, densely polluted, dangerously stratified, economically hyped, architecturally schizoid, dust-ridden modern metropolis, expanding away from its railroad tracks onto flattened layers of the mountainside.

When I left Tehran again, in 1986, it was a benighted city, endangered by nocturnal attacks of Iraqi planes, unraveling under the influx of war refugees from Afghanistan and the war-ravaged southern parts of Iran. It was economically enfeebled by an embargo, a war of attrition, and the flight of capital. The city was now mastered by zealots armed with guns and an infallible faith. They roamed the streets day and night, intent on creating a "new man" and a model new Islamic society.

As a metropolis, Tehran is an anomaly. Not only does the memory of its pastoral past - its winding labyrinthine alleys, its lack of a sewage system-encumber its expansion at every turn, it also lacks proximity to water. Seas and rivers are not just facilitators of trade, but also metaphors, mythically understood by humans, of openings, of journeys, of cleansing, of hope and utopia, and finally of fertility. Tehran has it's back to majestic mountains and its face to tormenting desert winds. It suffocates in the metaphor of its own geography.

(pages 131-136)By the end of my second year in Tehran, my ritual every morning and many times during the night was to look outside and survey the cars parked in the neighborhood. In politically oppressive societies paranoia is one of the smaller prices one pays for political activism. Nothing is coincidental. Every gesture, every move, every anomaly, and every event is a moment of grand, woeful design, and a potential source of danger. But all seemed safe that morning. The last few patches of blue sky were giving way to threatening gray clouds. Snow seemed imminent.

I had to be at the minister's house by eight. Many members of his think tank were now undersecretaries in the Ministry of Education. I had been offered a similar position and refused. By then I was already trying to disengage myself, and I participated in fewer and fewer of the group's functions. That morning we were to make a surprise visit to a school principal in the poorest section of Tehran who was reportedly pilfering the government-allotted student lunch fund.

The minister lived in an ornately handsome house, incongruent with the squalor of its once aristocratic neighborhood. The newly wealthy and some of the old-moneyed families of Tehran had moved to new suburbs, showplaces for gaudy and gothic architecture and marble-mania, while the sudden convergence of millions of people on Tehran, searching for their share of the petro dollar, turned more and more of the "urb" and its distinguished old neighborhood into a ghetto.

In the old days Samad's store was half a block from where the minister lived. What Fauchon is to gastronomy today, Samad was then to fruits and vegetables. The aristocracy, oblivious of cost and particular in their taste, shopped there. Others bought there for social status. Gas lights illuminated Samad; it was the most beautiful store of my childhood. The proprietor's cherubic face belied his cunning. Samad used no price tags, but charged what the customer would bear. When bananas were an oddity in Iran and strawberries a rare delicacy, I remember Samad's display of them by the colorful crate. The advent of supermarkets brought his demise. In place of his shop now stood a fifteen-story glass and steel high-rise, the national headquarters for Iran-Japan bank. I passed it on my way to the minister's house.

He greeted me in his usual congenial manner and ordered some tea. Before it arrived, the phone rang. He answered, exchanged the routine greetings, then just listened, losing color by the second. Finally he said, "Yes, his first name is Abbas," and after a bewildered glance at me, "Yes, he was educated in America, but it can't be him." Another pause, this time much longer. He promised to keep in touch. I was terrified.

In a voice more anguished than angry, he said, "It was from the security police. Your name has come up in connection with an opposition group. It isn't true, is it?"

With the bitter taste of fear puckering my mouth, soaked in cold perspiration, I mustered enough composure to deny the accusation. But I was already resigned to what I knew my fate would be.

The inspection at the high school lasted nearly four hours. We returned to the minister's office around noon. He told me he had arranged for me to meet with the head of internal security. "Be back by three," he said. I walked to his secretary's office to ask for a car. While I waited, two men entered. One of them whispered something to the secretary, and a couple of minutes later she told me my car was ready. When I left the room, the two men followed.

Outside, a heavy snow had begun. I climbed into the blue Chevrolet and gave the driver the address where I wished to go. As soon as he pulled outside the iron gates of the ministry, we were surrounded by a half dozen cars. Security forces in civilian clothes, brandishing their Uzis, rushed the Chevrolet as the driver grabbed my arms. Someone opened the car door and forcefully stuck his two hands into my mouth to hold it open in case I was carrying a cyanide pill and would kill myself before his superiors had their day with me.

I was shoved into the back seat of a Volvo, a guard on either side of me. In that flicker of a moment before they pushed my head down between my knees and pulled my jacket over my back, I saw the bewildered face of a bystander, and the pity so prominent in his eyes reminded me of religious occasions during my childhood, watching the slaughter of sacrificial lambs in our backyard. The car took off and one of the men sitting in front, clearly the commander of the crew, announced in his transmitter, "This is Shabdiz. The subject is in custody." Not long after that announcement, a voice on the transistor called Shabdiz and commanded him to also arrest the wife of the subject. "Back-up units forthcoming," the voice said.

Fereshteh's arrest and the subsequent search of our house for possible caches of leaflets, banned books, or guns took a long time. They found nothing. All the while, I sat in the back seat of the Volvo, watching first the arrest of my innocent wife, and then the search of our apartment.

Only moments after their search, around five o'clock in the afternoon, we arrived at what had come to be called the Komiteh. The early evening gloom only exacerbated my sense of despair. Once inside the Komiteh's big metal gates, the transmitter activated again. "Don't turn the subject in. Wait for further orders."

I, like others in the opposition, had by then heard of "safe houses" where no records of detention were kept and security forces could dispatch anyone into an abyss and add her or his name to the list of "the disappeared." The wait lasted an eternity. I remember the snowflakes seemed particularly graceful in their descent. While somewhere, unbeknownst to me, a bureaucrat who only knew me through the confessions wrung out of other prisoners, was deciding whether I should be filed away in some terminal "safe house," the crew of Shabdiz talked about soccer. "Turn him in," the voice finally said to my great relief, and thus began my six-month journey into the Komiteh.

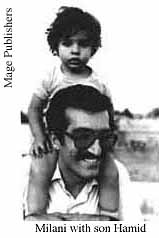

Raised in Iran, Abbas Milani was sent to be educated in California in the 1960s. He became politically active and in 1974 received a PhD in Political Science. He returned to Tehran and taught at the National University but was imprisoned by the Pahlavi regime in 1977. After the revolution he became a professor at Tehran University, but in 1986 he emigrated to the United States. He is currently Chair of the Department of Social Sciences at the College of Notre Dame in Belmont, California and is a frequent contributor to the San Francisco Chronicle.

|

|

|