The inside story

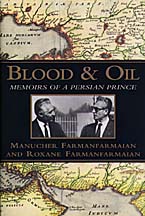

From the prologue of "Blood & Oil: Memoirs of a Persian prince" (Randon House, 1997, 514 pages. $35) by Manucher and Roxane Farmanfarmaian. (See interview with Roxane Farmanfarmaian. Click here for reviews. )

Embassy dinner

Civilized?

What went wrong?

Don't blame Iran alone

In and out of power

Democracy, human rights

All happened before

Open wounds

Story of oil

My children

A

few days ago I was invited to dinner at the Finnish Embassy. The house

was one I once owned. It lies just up the road from the embassy residence

I lived in when I represented the Shah and my country [as ambassador to

Venezuela]. Thank God! it was one of the few assets left to me when I walked

out of Iran in 1980 across the Turkish border with nothing but a suitcase.

On the way to dinner I passed the old residence I'd spent five such happy

years in. I'd named it Persepolis. Now it's called Omat, the Arabic word

for "people."

A

few days ago I was invited to dinner at the Finnish Embassy. The house

was one I once owned. It lies just up the road from the embassy residence

I lived in when I represented the Shah and my country [as ambassador to

Venezuela]. Thank God! it was one of the few assets left to me when I walked

out of Iran in 1980 across the Turkish border with nothing but a suitcase.

On the way to dinner I passed the old residence I'd spent five such happy

years in. I'd named it Persepolis. Now it's called Omat, the Arabic word

for "people."

Each time I see it I am affronted. At the very least, could not a Persian word have been found for the one building that represents the country in this foreign land? At the ambassador's yearly reception on February 12 marking the birth of the Islamic Republic, the women are consigned to a separate floor upstairs. No alcohol is served. The atmosphere is tense. Not surprisingly, few of the diplomatic community go. But I have made a point these years of attending.

The place has gone to seed. Much of it is now office space. The dining room is a dorm. The ambassadors are always young and speak no foreign language. They think they have a religious mission here. We greet each other warily. Like everyone else, I am a stranger in their house.

Over drinks at the Finnish Embassy I find myself being eyed by a tall, predatory woman. She turns out to be the wife of the Romanian ambassador.

"Everyone had such hopes for the new government," she says, referring to Rafael Caldera's recent surprise presidential victory after twenty years of being out of office. "But," and she looks disappointed. "Venezuela seems only to be getting worse."

I am not interested in talking politics. I think Caldera will stumble through, but he is too old, like me, for such a job. I am more taken by the way her dress falls into the curve of her bosom. I want to make advances, find out what terrain I'm in. I catch myself. "Every country gets the government it deserves," I say.

She purses her lips.

"Venezuela is not civilized," I add. "It's the jungle. What did you expect?"

"Not civilized?" she echoes. "Unlike Iran," she says seductively. I damn her persistence. "Now that was a civilized country -- under the Shah."

"Civilized?" I mock her. "Iran was never civilized. You make a mistake. It's got culture, of course. But it is not civilized. It's backward. It was backward under the Shah. It too got what it deserved."

By the way her eyes widen I can tell I've shocked her. I am pleased. I like shocking people. It makes for better conversation. The ambassadoress gathers herself together with admirable speed. "What about you then?" she asks. "What about you and all the rest of the elite, the poets, the artists..."

"They're gone," I say curtly. "And even they weren't civilized." I venture to put my hand on her elbow. "Watching television, wearing blue jeans, drinking Coca-Cola -- that's being modern, not civilized. Few read books or collected art. We were not patrons. Our European educators went only skin deep. Their gloss washed off the minute we returned to Iran. We did not bring discipline or order to our country. We allowed ourselves to live surrounded by ignorance. We were decadent, like the lords of the ancien r*gime. But instead of Napoleon we got Khomeini."

"Why," she asks. "What went wrong?"

Even as she asks the question, the host takes her arm and squires her in for dinner. She casts a long glance over her bare shoulder. There was a time I would have signaled the waiter to bring me a scotch and belted it down before facing her at dinner. But those days are gone. I am seventy-seven. I don't have the energy anymore. I've turned my back on Iran. I've finally left her to her wounds.

What went wrong? I have been asked that ever since I left Iran. For years I evaded the question. I knew I would only sound bitter. What's more, the eagerness in people's eyes turned my stomach. They did not want to know what really happened. If I spoke of the mistakes made by their own countries in Iran, they turned a deaf ear. They wanted to hear horror stories, exotic gossip to pass on about the frightening face of Islamic fanaticism. They wanted to hear condemnations -- and condemnations only.

I refused. Pride held my tongue. And shame. I needed to regroup, send down new roots before I could speak of Iran. Many dear friends were killed in the bloodbath of the revolution. For eight years after the revolution two of my brothers wallowed in Khomeini's prisons, and I rationalized silence as imperative to their protection.

By the time they were released, events had overtaken even my own experience in Iran: Its new martyrs were acting as minesweepers in the war with Iraq, Iran-Contra was in full swing, Salman Rushdie was a hunted man. At every turn Iran amazed and traumatized the world. And yet unlike Iraq it never invaded its neighbors. Unlike Syria it holds elections for its president and Parliament. Unlike Saudi Arabia it allows women to work and drive. No matter. Over the years its partiality for assassinations in Paris and its funding of the Hezbollah in Lebanon have further blackened its image. Outstripping Cuba and Libya, it has become the pariah of the world.

Each new revelation of Iran's excesses sickens me. But I do not blame Iran alone. I also blame England and the United States. This is not a case of isolated lunacy. Even now I see the same festering anger growing in easygoing Venezuela, in the violent outbursts in Somalia and Egypt, in the attitude of the well-heeled Asian nations that balked at what they called the imposition of Western norms at the Human Rights Conference in Vienna in 1993. Call it what you will: the malady of third-world servility, the David and Goliath syndrome, the maddening inability of those with power to learn from their mistakes.

Today Iran tops the list of Washington's "rouge nations." But the superpowers did much to mold it onto what it has become. Iran is where the double standard of international politics finally came home to roost. It is not a simple story.

I have watched Iran for more than fifty years as it has reeled and stumbled from one cataclysm to the next. The first shah to fall under British pressure was my second cousin, the last of the Qajar line, which had ruled Persia for 140 years. He wanted to be a constitutional monarch. The failing British empire wanted a dictator. Its ministers considered it easier to deal with one man than an independent parliament -- a policy they followed throughout the Middle East. It was just after World War I. The candidate they chose was Reza Shah, the first of the short-lived Pahlavi dynasty, a soldier who had worked for my father.

From then on my family was perpetually in and out of power and a constant discomfort to the throne. We formed a clan -- blue-blooded, educated, the wellspring of a harem. Even in Iran we were unusual. There was not a major event that took place in the span of this century where one of us was not prominent on the scene. Seven of my siblings or close cousins served at one time or another in the cabinet.

My brother Khodadad headed the Central Bank for a while. One of my sisters founded the School of Social Work and introduced family planning into Iran. Another married the head of [Tudeh] Communist Party. Four of my brothers started banks, among them the Bank of Tehran, the largest private bank in the country. Two were generals in the army. My brother Aziz founded the largest architectural firm in the Middle East; he built the airport and the Shah's own Niavaran Palace.

There were so many of us that in parties visiting foreign dignitaries would hear our name repeated so often that they would mistakenly think it a form of salutory address and start saying Farmanfarmaian themselves as they made their introductions and shook hands. We thought it amusing. We were used to the Farmanfarmaian name being magic...

Although there were times when we were genuinely close to the royal family, our relationship with the Pahlavis was always charged. For good reason they never stopped being suspicious. Three times we were credited with threatening the throne, and each time they held on to it only through foreign intervention. We represented a side of Iran they could never tap -- the gossamer web of loyalty between landlord and peasant, and between landlord and tribe.

Why do I understand the actions of Iran today? Because I know her underbelly. I can tell you why xenophobia toward the West exceeds that of any country in the world. I have seen it grow like wheat in my own fields. I have seen the men who sowed it: smart English colonels with whips and colonial mentalities just off the boat from India; fresh-faced Americans from Point Four Program who had never worked the land but who, with the best of intentions, counseled the peasants to change what had worked for a thousand years and instead store their grain the way they did in Iowa. When the villagers were beaten like oxen and their grain rotted, when they saw the British and American troops impound their bread and march across their land to protect them from the threat of communism -- is it any wonder that they felt cheated and used and wrote "Yankee go home" on their mud village walls?

Democracy, human rights. To the common Iranian these words just mean more famine, poverty, and corruption. To the intellectuals they mean two-faced political intrusion. Why did President Jimmy Carter tell the Shah to improve his human rights record, they ask, when he never uttered a word to England about getting out of Gibraltar? Why has the United States still never told Saudi Arabia to free its women? Unlike the simple appeal of communism, which told the poor to kill the rich and take the land, democracy could never muster grassroots enthusiasm in places like Iran. In all my life I have yet to see a spontaneous demonstration for democracy. It's too complicated a creed. It requires professional politicians and organized media.

What's happening now in Iran has all happened before. I've seen it two, three times -- the violent separation from a superpower, the shudder to live up to its own sense of sovereignty, the shattering disappointment. When Mohammad Mossadeq, my cousin, ran the Shah out of Iran in the 1950s and nationalized oil, his actions were ill-conceived and as regressive as any of Ayatollah Khomeini's. Iran was as isolated then as it is now. Opposition was silenced by threat of assassination or, worse, public accusation of collusion with the British government. Many in London and Washington thought Mossadeq was a madman. He wasn't. He tried to do good by Iran. He was loved by the people. He evinced a simple honesty the Shah never attained. He permanently evicted the British from the oil fields. But in all else he failed.

In Iran the wounds are still open. In a country that rebuffed the Romans in the third century and took the emperor Valerian prisoner, a country that redefined the Arabs' Islam and made it its own, nothing is done halfheartedly. Yet in Washington, London and the United Nations, the slate has been cleaned by collective amnesia. Events have moved on. To most Americans the Khomeini era is so bizarre it's inexplicable. They don't care that it's the most recent chapter of a long history. Some don't even know the difference between Persia and Peru. "You're from Persia?" said the man next to me on a plane not long ago. "That's next to Columbia, right?" Yes, I nodded, and left it at that.

Am I saying that Iranians are not responsible for their actions? I would never say that. We are our own greatest victims. It is a question of perspective. Westerners have never heard it from the Iranian point of view. Quotes from the Iranian papers never make it into the New York or London Times. You would understand more if they did. You would know, for instance, that there is more to the story of oil. For us it is as much a curse as a treasure. You would know that tons and tons of it were stolen, wasted, fought over, that people died mysteriously, that millions of dollars disappeared. The accounts were all in my files at the Ministry of Finance when I was director of concessions.

Later, when I was on the board of the National Iranian Oil Company, I showed our numbers to other oil-producing nations. They were appalled. That is why my signature was at the top of the protocol that created OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. This is a matter of public record. The notes and numbers are in the British national archives, typed in carbon on dusty onionskin. Today the only ones who read them are angry Iranian students -- and people digging up the past, like me.

Every once in a while my children ask me what properties we still have back in Iran. They hope to return to sometime and reclaim what is rightfully theirs. I know they've had their heritage cut off at the knees. They feel a rootlessness, a gap in their lives that Venezuela has filled for me but not for them. Nonetheless, I cannot bring myself to sit down and make them a list.It all seems so pointless. My elder brother still lives in Tehran in my father's old summer house. It has been his house for fifty years. He does not dare leave even on a short vacation. If he does, the revolutionary guards have warned him they will move in.

But a country is like a woman -- no matter how ugly, it always has its lovely angles. That is why I am finally telling this story. "Persians don't write memoirs," said one of my earliest mentors many years ago in London. "They are not like the British, whose adventures and ambassadors have written whole libraries for their countrymen to read." From that moment on I decided to leave behind a record. All my life I collected filed. When these were abruptly lost during the revolution, I was left with only my recollections. At the time they seemed woefully thin. I am an engineer. I'm used to backing up my statements. That's my Western side, drilled into me by my very British education. My Eastern side pushes me to spin the tale.

As the sun sets over the terrace I go inside and begin to talk to my daughter. Together we find the right words. That too has been a revelation. It is not in my nature to talk so to women. I am a man who lives alone and thinks alone. Nevertheless, as the story of my country has unfolded night after night, we have become friends. If I cannot give her the earth of her country, at least I've been able to share with her the lost world in my mind.

She asks me to warn you of one thing. The tales are all true, but they are like kaleidoscopes: Turn them a different way, and you see a different set of images.

I will tell you a story. It is about a friend of mine, a landlord with property just over the hill from our place in the western district of Kermanshah. It was winter and he sat chilled and lonely in front of his fire. Toward evening his servant announced that a traveling poet was at the door.

"Show him in," said the landlord, suddenly cheered at the thought of company. He ordered sweets and hot tea, and when the visitor appeared, he motioned him to a cushion next to his own.

The evening passed quickly after that, for the poet was entertaining and adept with his rhymes. When at last the evening wore down, the poet got to his feet and, bowing, spoke a final ode to the landlord, complimenting him lavishly for his wisdom and grace and praising him beyond all others for his generosity.

The landlord was moved. "How sweet are your words," he said. "For that I will grant you a hectare's worth of spring wheat in gold when it is harvested from my fields."

Now it was the poet's turn to be moved. He fell to his knees and kissed the landlord's robe. Each parted that evening with a bright glow in his heart.

In late July the poet returned to the estate. He walked down the road with a strut, for he knew he would soon be a rich man. At the castle gate he demanded loudly to see the landlord.

"I've come to collect my hectare's worth of wheat in gold," he announced, throwing himself to the ground when the landlord appeared. "You do remember that cold night when we shared a few hours of poetry together?"

The landlord looked at him blankly. Then his brow cleared. "Of course I remember," he said. "And what a cold night that was. But why did you say you've come back?"

"To collect the gold, sir, which you promised me that night," answered the poet.

"Ah," said the landlord. "But that was winter and now it's spring. Get up and be off with you, dear poet. You said something to please me that night, and I said something nice to please you. Though you did not really believe all those things you said to me, I went to bed feeling good indeed. I felt so fine, in fact, I wanted you to feel good too. And so, because I'm a landlord not a poet, I promised you a harvest of wheat, hoping the thought of all that gold would give you pleasant dreams." #

Reviews of "Blood & Oil"

* Abbas Milani's review

in the San Francisco Chronicle

* John Maxwell Hamilton review

in the Chicago Tribune

* Geoffrey Wheatcroft's review

in The New York Times

Manucher Farmanfarmaian was born in 1917. In 1958 he became director of sales for the National Iranian Oil Company. A key signatory of the 1959 Cairo agreement that resulted in OPEC, he was Iran's first ambassador to Venezuela.

Related links

* THE IRANIAN Bookstore

* Cover stories

* Who's

who

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved. May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

|

|

|