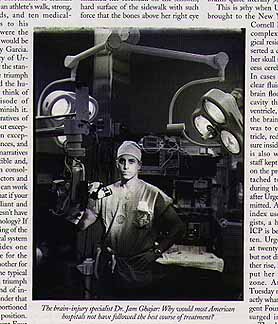

Dr. Jamshid Ghahremani Ghajar featured in The New Yorker.

![]()

From Conquering the Coma by Malcolm Gladwell in the July 8, 1996,

issue of The New Yorker magazine.

On the afternoon of Tuesday, June 4th, a young woman was taken by ambulance

from Central Park to New York Hospital, on the Upper East Side. When she

arrived in the emergency room, around four o'clock, she was in a coma, and

she had no identification.

Her head was, in the words of one physician, "the size of a pumpkin." She was bleeding from her nose and her left ear. Her right eye was swollen shut, and the bones above the eye were broken and covered by a black-and-blue bruise. Within minutes, she was put on a ventilator and then given X-rays and a CAT scan. A small hole was drilled in her skull and a slender silicone catheter inserted, to drain the pressure steadily building in her brain.

At midnight, after that pressure had risen precipitously, a neurosurgeon removed a blood clot from her right frontal cortex. A few hours later, Urgent Four -- as the trauma-unit staff named her, because she was the fourth unidentified trauma patient in the hospital at that time -- was wheeled from the operating room to an intensive-care bed overlooking the East River.

Urgent Four -- or the Central Park victim, as she became known during the spate of media attention that surrounded her case -- came close to dying on two occasions. Each time she fought back. On Wednesday, June 12th, eight days after entering the hospital, she opened one blue eye. The mayor of New York, Rudolph Giuliani, was paying one of his daily visits to her room at the time, and she looked directly at him.

Several days later, she began tracking people with her one good eye as they came in and out of her room. She began to frown and smile. On June 12th, the neurosurgeon supervising her care leaned over her bed, pinched her to get her attention, and asked, "Can you open your mouth?" She opened her mouth. He said, "Is your name ----?" She nodded and mouthed her name.

There is something compelling about such stories of medical recovery, and something undeniably moving about a young woman fighting back from the most devastating injuries. In the days following the Central Park beating, the case assumed national proportions as the police frantically worked to locate Urgent Four's family and identify her attacker.

The victim turned out to be a talented musician, a piano teacher beloved by her students. her alleged assailant turned out to be a strange and deeply disturbed unemployed salesclerk, who veered off into Eastern mysticism during his interrogation by the police.

The story also had a hero, In Jam [Jamshid Ghahremani] Ghajar, the man who saved her life: a young and handsome neurosurgeon with an M.D. and a Ph.D., a descendant of Iranian royalty, who has an athlete's walk, strong, beautiful hands, and ten medical-device patents to his name. If this were the movies, Ghajar would be played by Andy Garcia.

Ghajar is, at forty-four, one of the country's leading neuro-trauma specialists. On his father's side, he is descended from the family that ruled Persia from the late seventeen hundreds until 1925, and his grandfather on his mother's side was the Shah of Iran's personal physician.

Neurosurgeons, Ghajar says, are "overachievers," and the description fits him perfectly. As a seventeen-year-old, he was a volunteer at the Brain Research Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). As a seventeen-year resident of New York Hospital, he invented a device -- a tiny tripod to guide the insertion of ventricular catheters -- that made the cover of the Journal of Neurosurgery.

Today, Ghajar is the chief of neurosurgery at Jamaica Hospital, in Queens. He is also the president of the Aitken Neuroscience Institute, in Manhattan, a research group that grew out of the double tragedy experienced by the children of Sunny von Bülow, who lost not only his mother to coma but also their father, Prince Alfred von Auersperg, after a car accident, thirteen years ago.

Most days, Ghajar drives back and fourth between the hospital and the institute, juggling his research at Aitken, with a clinical schedule that keeps him on call two weeks out of every four. "Jam is completely committed -- he's got a razor-sharp focus," Sunny von Bülow's daughter, Ala Isham, told me. "He's godfather to my son. I always joke that we would carry little cards in our wallets saying that if anything happens to us call Jam Ghajar."

Ghajar spent all day Tuesday, June 4th, at Jamaica Hospital. In the evening, he returned to the Aitken Neuroscience Institute, where a colleague, Michael Lavyne, told him of the young woman hovering near death across the street at New York Hospital.

At seven o'clock, Ghajar left his office for the hospital. Two hours later, with Urgent Four's ICP at dangerous levels, he ordered a second CAT scan, which immediately identified the culprit: the bruise on her right frontal cortex had given rise to a massive clot. At midnight, Ghajar drilled a small hole in her skull, cut out a chunk three inches in diameter with a zip saw, and, he said, "this big brain hemorrhage just came out -- plop -- like a big piece of black jelly."

Had Urgent Four been taken to a smaller hospital, or to any of the thousands of trauma centers in America which do not specialize in brain injuries, the chances are that she would have been dead by the time any of her family arrived.

This is what trauma experts who are familiar with the case believe, and, of the many lessons the Central Park beating, it is the one that is hardest to understand. It's not, after all, as if Urgent Four were suffering from a rare and difficult brain tumor. Brain trauma is the leading cause of death due to injury for Americans under forty-five, and results in the death of some sixty thousand people every year.

Nor is it as if Urgent Four had been given some kind of daring experimental therapy, available only at the most exclusive research hospitals. The insertion of the ventricular catheter is something that all neurosurgeons are taught to do in their first year of residency. CAT scanners are in every hospital. The removal of Urgent Four's blood clots was straightforward neurosurgery. The raising and monitoring of blood pressure are taught in Nursing 101.

Urgent Four was treated according to standards and protocols that have been discussed in the medical literature, outlined at conferences, and backed by every expert in the field. Yet the fact is that if she had been taken to a smaller hospital or to any one of the thousands of trauma centers in American which do not specialize in brain injuries she would have been treated very differently.

When Ghajar and five other researchers surveyed the country's trauma centers five years ago, they found that seventy-nine percent of the coma patients were routinely given steroids, despite the fact that steroids have been shown repeatedly to be of no use -- and possibly of some harm -- in reducing intracranial pressure.

Ninety-five percent of the centers surveyed were relying as well on hyperventilation, in which a patient is made to breath more rapidly to reduce swelling -- a technique that specialists like Ghajar will use only as a last resort. The most troubling finding, however, was that only a third of the trauma centers surveyed said that they routinely monitored ICP at all.

Most neurosurgeons make their living doing disk surgery and removing brain tumors. Trauma is an afterthought. It doesn't pay particularly well, because many car-accident and shooting victims don't have insurance. (Urgent Four herself was without insurance, and a public collection has been made to help defray her medical expenses.)

Nor does it pose any kind of medical challenge that, say, an aneurysm or a tumor does. "It's something like -- well, you've got mashed-up brains, and someone got hit by a car, and it's not really very interesting," Ghajar says. "But brain tumors are kind of interesting. What's happening with the DNA? Why does a tumor develop?"

Then, there are the hours, long and unpredictable, tied to the rhythms of street thugs and drunk drivers. Ghajar, for example, routinely works through the night. he practices primarily out of Jamaica Hospital, not the far more prestigious New York Hospital, because Jamaica gets serious brain-trauma cases every second day and New York might get one only every second week.

"If I were operating and doing disks and brain tumors, I'd be making ten times as much," he says. In the entire country, there are no more than two dozen neurosurgeons who, like Ghajar, exclusively focus on researching and treating brain trauma.

Ghajar says that in talking to other neurosurgeons he sensed a certain resignation in treating brain surgery -- a feeling that the prognosis facing coma patients was so poor that the neurosurgeon's role was limited.

"It was just that there was so much information out there that it was confusing. When they got young people in comas, half of the patients would die. And the half that lived would be severely disabled, so the neurosurgeon is saying, 'What am I doing for these people? Am I saving vegetables?' And that was honestly the feeling that neurosurgeons had, because the methods they were trained in and were using would produce that kind of result."

Three years ago, after a neurosurgery meeting in Vancouver, Ghajar -- along with Randall Chesnut and Donald W. Marion, a brain-trauma specialist at the University of Pittsburgh -- decided to act. For help they turned to the Brain Trauma Foundation, which is the education arm of the brain-trauma institute started by Sunny von Bülow's children.

The foundation gathered some of the world's top brain injury specialists together for eleven-meetings between the winter of 1994 and last summer. Four thousand scientific papers covering fourteen aspects of brain-injury management were reviewed. In March of this year, the group produced a book -- a blue three-ring binder with fifteen bright-colored chapter tabs -- laying out the scientific evidence and state-of-the-art treatment in every phase of brain-trauma care.

The guidelines represent the first successful attempt by the neurosurgery community to come up with a standard treatment protocol, and if they are adopted by anything close to a majority of the country's trauma centers, they could save more than ten thousand lives a year. A copy has now been sent to every neurosurgeon in the country.

In his first week back on call after the Urgent Four case, Ghajar saw three new coma patients. The latest was a thirty-year-old man who had barely survived a serious car accident. He was in worse shape than Urgent Four had been with a hemorrhage on top of his brain.

He was admitted to Jamaica Hospital on Monday at 11 P.M., and Ghajar operated from midnight to 6 A.M. He inserted a catheter in the patient's skull to drain the spinal fluid and monitored his blood pressure, to make sure it was seventy points higher than his ICP. Then, that evening -- fourteen hours later -- the patient's condition worsened. "I had to go back in and take out the hemorrhage," Ghajar said, and there was a note of exhaustion in his voice. He left the hospital at one o'clock Wednesday morning.

"People want to personalize this," Ghajar said. He was on Seventy-second Street, outside his office, walking back to New York Hospital to visit Urgent Four. "I guess that's human nature. They want to say 'It's Dr. Ghajar's protocol. He's a wonderful doctor.' But that's not it. These are standards developed according to the best available science. These are standards that everyone can use."