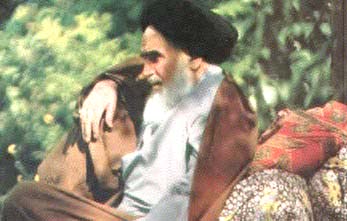

Photo thanks to Yari Ostovany

Khomeini turbulent priest who shook world

By Paul Taylor

LONDON, Jan 28 (Reuters) - A frail, white-bearded man sat cross-legged

on a Persian rug in a suburban bungalow near Paris and spoke in a faint

monotone into a cassette-recorder. And the world trembled.

Twenty years ago next week, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, an ascetic

Shi'ite Moslem clergyman, returned to Iran to a tumultuous welcome to lead

one of this century's great upheavals -- the first Islamic revolution.

Exploiting a national network of mosques, the Shi'ite cult of martyrdom

and the strange indecisiveness of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Khomeini

replaced one of the Middle East's richest U.S.-backed oil monarchies with

an austere theocratic state.

``We will end foreign domination in Iran. America cannot do anything,''

the ayatollah vowed in an interview with Reuters shortly after he settled

in the village of Neauphle-le-Chateau, near Versailles, in October 1978.

``Do not be afraid to give up your lives and your belongings in the

service of God, Islam and the Moslem nation,'' he told his followers in

one of the taped messages that sent millions of unarmed demonstrators into

the streets to brave the Shah's army.

KHOMEINI'S SYSTEM ENDURES

Unlike many revolutionary systems, the Islamic republic that Khomeini

built has endured despite a 20-year confrontation with the United States,

an eight-year war with Iraq and waves of bombings, assassinations, executions

and power struggles.

Khomeini, who became supreme leader with sweeping powers under the constitution

adopted in 1979, died in his bed a decade later, revered by most Iranians

but reviled in the West.

His mausoleum in south Tehran is a shrine for pilgrims.

While the revolution devoured many of its children in spasms of violence,

Moslem clerics still wield most power in Iran.

The complex institutional checks and balances developed by Khomeini

to guard against a coup and prevent one faction from monopolising power

provide the framework for a permanent power struggle among his heirs.

The contrast between the Shah, whose imperial family flaunted its fabulous

petrodollar wealth in gaudy ceremonies, and the ayatollah, who lived frugally

on a diet of bread, fruit, nuts and yoghurt, could hardly have been more

stark.

Twice a day, the stern old man in dark robes and a black turban indicating

descent from the Prophet Mohammed, crossed the Route de Chevreuse under

French police guard to lead prayers and deliver sermons in a blue-and-white

tent pitched in the garden of the two-storey house that served as his headquarters.

Students, businessmen, clergymen and politicians flocked to Paris from

Iran and the diaspora in Europe and the United States to talk and pray

with Khomeini after president Valery Giscard d'Estaing gave him temporary

refuge.

The ayatollah listened to moderate advice but held firm to his course,

dismissing calls for compromise to avert bloodshed.

``There will be no compromise with the Shah. Until the day an Islamic

republic is established in Iran, the struggle of our people will continue,''

Khomeini said in the interview.

The turbulent cleric had been expelled from Iraq under pressure from

the Shah, seeking to end a snowballing revolt against his rule spearheaded

by Shi'ite religious leaders, demonstrating students and striking oil workers.

He had launched his battle to drive the Shah from his ``peacock throne''

in 1962-63, condemning the monarch's White Revolution land reforms as un-Islamic

and denouncing the immunity privileges of U.S. advisers and oil companies

in Iran. He was exiled first to Turkey, then to the holy city of Najaf

in Iraq.

WESTERN-TRAINED ADVISERS ROSE AND FELL

In Neauphle-le-Chateau, Khomeini was surrounded by a circle of Western-educated

aides who went on to play key roles in the early revolutionary governments

before being sidelined by Islamic hardliners.

A large sign in English and Persian outside Khomeini's headquarters

proclaimed ``The ayatollah has no spokesman.'' But the men who assured

journalists that Iran would be a liberal Islamic democracy would qualify

nowadays as spin doctors.

Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, an economist who lived in Paris, acted as his

interpreter and secretary. He was elected the first president of the Islamic

republic in 1980 before being hounded from office by hardline mobs a year

later, fleeing for his life to the French capital.

Sadeq Qotbzadeh, a former anti-Shah student activist expelled from the

United States in 1969 and who had a Syrian passport, became head of radio

and television, then foreign minister. He resigned in 1980 and was executed

in 1982 for allegedly plotting to overthrow Khomeini.

Ebrahim Yazdi, a cancer researcher who lived in Texas, was Khomeini's

chief English-speaking aide. He sought to persuade the West that the Islamic

movement was not manipulated by the Soviet Union or bent on anarchy.

He became foreign minister in the first revolutionary government but

was forced out for trying to end the occupation of the U.S. embassy by

militant students in November 1979 after Washington admitted the deposed

Shah for medical treatment.

Yazdi today heads a small, semi-legal opposition party, the Iran Freedom

Movement, but has little influence.

Khomeini's other confidant was his second son Ahmad, a mullah (clergyman)

who was his closest aide during his decade at the helm of the Islamic republic

and the key link with the students occupying the U.S. embassy. He died

in 1995.

Khomeini's elder son, Morteza, had died during their exile in Iraq after

being visited by two Iranians suspected of being agents of the Shah's hated

SAVAK secret police.

The ayatollah's wife, Batul, accompanied him in France but played no

public role.

RETURN TO IRAN

Interviewing Khomeini was a strangely impersonal experience. Questions

were submitted in writing and Bani-Sadr translated the written replies

before the reporter was admitted for a brief meeting with the ayatollah.

There was no handshake. Khomeini stared at the carpet while speaking

rather than seeking eye-contact with the interviewer.

Some of his delphic statements required interpretation. When he said:

``We will cut off the hands of the foreign agents,'' aides hastened to

explain he meant rooting out foreign domination in Iran, not severing limbs.

As the revolution moved towards a climax, sending world oil prices soaring

to record levels, the throngs of supporters and journalists swelled at

Neauphle.

The French authorities who had initially treated Khomeini with caution,

warning him three times to refrain from political statements, gave him

VIP treatment.

Two weeks after the Shah left Iran on ``holiday'' on January 16, never

to return, the ayatollah, his entourage and several dozen journalists boarded

an Air France jumbo jet for Tehran, despite threats by the Iranian government

to shoot it down.

The volunteer crew had take on twice the normal load of fuel in case

they were forced to turn back. The plane had to circle for more than half

an hour over Tehran while final negotiations for permission to land were

conducted.

A crowd estimated at more than one million people was waiting to greet

the revolution's spiritual leader as the Air France stewards helped him

down the gangway at Mehrabad Airport.

Ten days later, the remnants of the Shah's last government under the

hapless prime minister Shahpour Bakhtiar were swept away in street battles.

The Middle East was never the same again.

Links

![]()