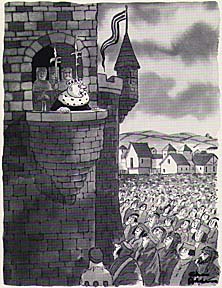

"And now, as an experiment in democracy, I'm

decreeing free elections to choose the national bird."

Courtesy, The New Yorker

From populism to pluralism

The Islamic Republic in transition

By Kazem Alamdari

May 8, 1998

The Iranian

Summary

Class theory and analysis cannot explain the current Iranian political power structure. Since the 1979 revolution, the power structure has moved from populism to clientelism, and is now moving toward pluralism.

Seventy years of conflict and challenge between traditionalism and modernity, finally ended in the Islamic revolution in 1979. This era had begun with the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-11 in Iran, changing a despotic feudal kingdom into a constitutional monarchy. Seventy years later, the constitutional monarchy ended with another major revolution.

Populism

The 1979 revolution was the outcome of a cultural lag and identity crisis brought about by the Shah's Westernization policies. Clerics seized power in the absence of secular political parties. The victory of the revolution changed the class structure of a semi-agrarian society led by a populist regime with its charismatic leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

After the revolution, power struggles pushed society into permanent revolution. First, radical and then conservative clerical factions of the Islamic Republic used revolutionary slogans to suppress all opponents and defeat all liberal and secular rival groups in the ruling circle.

Had the war with Iraq not occurred, populism could have ended within a short period after the revolution, and Iran could have begun its routinization and institutionalization. Iraq's invasion in 1980 and the start of the war, however, empowered the populist Islamist forces and triggered similar movements abroad as Iran aimed to export the revolution.

Populism finally ended with the termination of the winless war, and the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989. No one could replace Khomeini's unique persona who was a religious, political and spiritual leader of millions of people. The Council of Experts' selection of the new supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, was the genesis of the crack within the ruling clerical groups. Khamenei is not a marja' (source of emulation) although that is a requirement for Islamic leadership. His selection was merely a political decision. In addition, the absence of a populist leader after Khomeini's death resulted in a dispersal of millions of supporters who became disillusioned toward Islamic slogans.

Clientelism

The failure of the Islamization of society marked the beginning of clientelism. Clientelism is a system of multiple vertical power centers of rival groups in a society, bounded by patrons and clients. Religious populism was replaced by political clientelism. In the new system, some of the faithful original supporters of an ideologically-based Islamic government became advocates of the current state for some reciprocal political and socioeconomic benefits. They became the beneficiaries of the status quo, not supporters of the "rule of virtue" as they once were. During the strong leadership of Khomeini, all rivals or internal opponents were suppressed, as his authority was unquestionable. After his death, various power centers grew separate from the central government.

Hojatoleslam Hashemi Rafsanjani, the second powerful man after Khomeini and the president at the time, made a shift toward "rational" capitalism to end the chaotic economic situation. To achieve his goals, Rafsanjani deserted the radical Islamists, who prefered the state economy, and allied himself with the conservative clergy and the bazaar merchants who favored a free market economy. He adapted the International Monetary Fund's Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), and gestured as a moderate political leader with a tendency to make concessions with the west. The privatization of the state owned economy, as part of SAP, virtually facilitated commercial and speculative capitalism to grow further. The productive sector continued to remain depressed. After a few years, Rafsanjani lost his dominant power to conservative rivals, among them Ayatollah Khamenei, the supreme leader, who openly sided with Rafsanjani's opponents. Clientelism, therefore, expanded.

Today

The current political power structure in Iran is neither a class system, nor a theocracy. Instead of an hierarchy of horizontal layers of classes made up of bureaucratic power centers, there are many vertical columns of rival ruling groups (patron-clients). In a recent interview, Rafsanjani, the current head of the Expediency Council, complained that: "In Iran many prefer to form bands rather than political parties, because it leaves them unaccountable." This clearly exemplifies a political system based on clientelism.

Iran is the only country in the world with two official armies, two judicial systems, many contradictory economic and financial policies, and several parallel, selective and elective political leaders. General, and local governors of provinces and cities, Friday Prayer (congregation) leaders, and Imams at thousands of mosques challenge and contradict each other and the elected government. Eighteen years after the 1979 revolution, the Revolutionary Guards, the Revolutionary Courts, and the Basij (popular militia) continue to dominate society as if the revolution continues.

In short, there are many autonomous power centers at local and national levels operating independently from the elected government. Financially, many of these organizations are self-sufficient as they either have charity and endowment incomes or budgets allocated by the government, or both. These institutions are society's actual power centers, ignoring laws and elected officials. "There are self-made governments that even the elected government cannot control," wrote Mobien, a weekly paper in Iran. "Some of these institutions, like Bonyad Mostaza'faan va Janbaazaan (Foundation for the Oppressed and War Disabled) are as big as the elected government itself and control vast assets as large as those of the government," writes another paper, Neda-ye Daaneshjoo (Students Tribune).

Among many large and small power centers, several are parallel with and even more powerful at a national level. On the top is the supreme leader, then the president, followed by the Expediency Council, the speaker of the Majlis (parliament), the Revolutionary Guards, the Intelligence Ministry, the Revolutionary Courts, the chief of the political prisons, Council of Guardians, Council of Experts, and Bonyad Mostaza'faan va Janbaazaan (Foundation for the Oppressed and War Disabled). But the question is whether these power centers are able to maintain their current positions or the new trend will institutionalize them.

Power shakeup

The surprise election of the new president, Mohammad Khatami, has shaken all centers of power, including that of the supreme leader. For the first time two prominent religious leaders, Ayatollah Montazeri who was forced to resign as the successor to Khomeini, and Ayatollah Azari Qomi, former chief persecutor of Revolutionary Courts and founder of the leading conservative newspaper Resalat, publicly challenged the absolute power of the supreme leader. In response, street demonstrations have been held in several cities to denounce these leaders.

The Islamist Student Organization, also moved to challenge the absolute power of the supreme leader, demanding that he must be elected, serve a fixed term, and be accountable. The new era has been marked with a major change or miscalculation of the ruling group in the presidential election. All previous presidential elections were the results of concessions by various power groups behind closed doors. Khatami is, however, a truly-elected president in an open race. "Past elections were not real. All factions would agree on a candidate and then a few others were put into the race in order to make the election look real,... this time we changed that process... people participated in the election, because they understood this change...," said Mohsen Rezaie the former commander of the Revolutionary Guards, and the current secretary of the Expediency Council.

Opponents of the Islamic system, international human rights organizations and foreign countries must recognize the new circumstances in order to help bring about change. The Islamic Republic is facing a serious crisis regarding its interpretation of Islam. The conservatives and fanatics, who lost the election, are loosing ground. Many clergymen acknowledge that a radical change is needed, if they are to survive. "Clergymen have lost their influence over the people," said Ayatollah Amini, the vice president of the Council of the Experts, the body which selects the supreme leader.

Pluralism

Recent political events, including the detention of Tehran Mayor Gholam-Hossain Karbaschi followed by furious public reactions, and the house arrest of Ayatollahs Montazeri and Azari Qomi reveal the depth of the conflict between reformers and conservatives. Religious leaders cannot rule as they have in the past. People, though indirectly, will challenge the system. They are tired of revolution, slogans, and empty promises.

With Khatami's election, Iran has entered into a distinct era. Unlike his predecessors, the new president has the will to bring about change. In addition to a major shift in Iran's foreign policy, domestically Khatami has put an emphasis on law, order and democracy. Political parties, civil society organizations and non-governmental organizations are encouraged. This trend, though very bumpy, breaks the clientelist system -- which is the main obstacle to change and development in Iran -- and makes the elected government accountable.

About the author

Kazem Alamdari is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at California State University, in Los Angeles.Dr Alamdari received his PhD from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His area of specialization includes Third World Development and Social Change, Democratization in the Third Word, Middle Eastern Studies, Islamic societies and Iran. He has published several articles both in English and Persian, and has given talks on Muslim, Arab and Iranian communities throughout the United States. He has taught at several institutions, including University of Tehran, and University of California, Los Angeles. (back to top)

Related links

* Opinion section

* Cover stories

* Who's

who

* Bookstore

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved. May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

|

|

|