Absence

Traveling to Iran after twelve years

Part One of three

By Laleh Khalili

September 1997

The Iranian

The Arrival

One day you wake up after a long period of prosperity and blissful

self-inflicted denial and find that in that visceral compartment where

one stores memories of birth and childhood you have developed a persistently

aching wound. You know the cause. Perhaps, you even know the cure. But

you skirt around the remedy in extravagant circles. You re-align your life

such that a fundamental part of your vocation becomes hearing and reading

about Iran. Labor of love, you guess. But that, though greatly satisfying,

does not address the bruised wound beneath your sorrow.

Finally, you gather enough guts and dollars to buy a ticket from an Internet travel agent you have found in your electronic search for anything that smells of spicy and warm Jahrom nights. You pack up your clothes and the sixty-plus, obligatory made-in-America souvenirs you have bought for the near and distant family members, hoping that the cadeau will match the person, and despite or maybe because of all the dire warnings of your expatriate father (whose suffering justifies his paranoia) you fly home.

You suddenly realize on the flight that although you have thought and dreamt in English for 12 years, that although Americans mistake you for Italian or Spanish, that although you now know the shortcuts and secret hideaways and best restaurants of New York and Atlanta and Houston, home to you is still the now-vague-image of Iran. Your first encounter with Iran "the-country", not Iran "the-people" or Iran "the-idea", in so many years is the sleek, surprisingly well-kept Iran Air jumbo jet at one of the gates of Istanbul Airport, the blue Homa emblem on its tail, still.

And you are shocked to find yourself openly weeping in great fundament-shaking sobs, in relief and joy and apprehension. This weeping woman is you; your interior and exterior finally meeting in a violent and familiar handshake. You find it ironic that a lovely Iranian family in that gate area summons their English-speaking teenage daughter so she can ask you in English about your origin and your destination. To her, to them, you look and - you suppose - act foreign enough to warrant the foreign-language question. When you answer haltingly, proudly, and in emphatic Farsi that you are Iranian, the daughter is definitely embarrassed and runs away.

The lovely family continues to ask you friendly questions though, seemingly and kindly not minding your broken Farsi and your American accent (you tell them and many others throughout your trip that you feel like Ibrahim Yazdi after his return to Iran immediately after the revolution when all the satirical newspapers savaged his accent and his frequent usage of English words for which he could not find a Farsi substitute in time).

Your Turkish Airline flight from Istanbul to Tehran is late by two hours and you - despite having traveled for a living and being accustomed to and tolerant of even-longer delays - find these two hours excruciating, as it seems like there is a fist deep down inside you somewhere that just won't loosen its grip on you. You have an eight hour lay-over but after rapid consideration, you won't even bother going into Istanbul-proper lest you miss your flight.

Sitting in the transit lounge is a good transition for you. You watch the crowd - your fellow countrymen and women - with a mixture of awe and familiarity. These people, dark and beautiful, smoking, curious and tired, look like members of your family. You strain to hear their conversation, hoping to be reminded of enough ta'arof and niceties to get you through the first few days. Your flight includes a rare sight: two teams of young volleyball-playing men from Slovenia and Greece heading to Tehran for 24 days for some sort of championship or other. Some of them drink whiskey until a few minutes before landing at Tehran's Mehrabad airport.

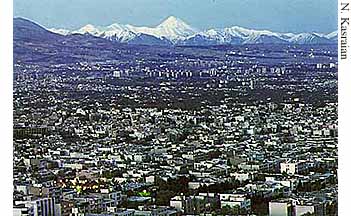

Circling over Tehran is an experience for you. You didn't anticipate this vast and lazy sprawl at the feet of Alborz mountains. And you certainly didn't expect the profusion of lights delineating highways and neighborhoods. In your memories, which are now beginning to seem jaded and inadequate, the electricity shortages and the wartime blackouts loom large. During the approach, you fortify yourself against the probable encounter at the customs line. You don't know what will be said to you when your father's name is read on your passport. You don't know if the much-heard-about passport control computer systems hold some deep dark directive against your entrance into the country. You don't know if you have to explain away or give up the books, the makeup, the perfume, the clothes you have brought back as gifts.

By now, it's 3:20 a.m. Tehran time, and on top of the apprehension, you feel guilty about your uncle waiting for you out there... and from the horror stories you have heard, it could take you some time - and dollars - to get past customs. Then the plane lands, and the stairs are attached, and the women adjust (or wear) their scarves and their shapeless coats. The air in Tehran is warm and velvety. You had expected a heavy rush of smog, but you don't smell anything but the ordinary smell of airports.

No fariytales here; but no nightmare either. At the passport control line, you watch as in a couple of instances, some passengers argue with officials. You also notice the colorful scarves and the makeup and the painted toenails peeking from the sexy European-looking open-toed sandals of female passengers. This is not quite what you expected either. You, in your black mantaux and your black scarf feel decidedly unfashionable in comparison with the bottle-blonde and beautifully made-up multitudes of gorgeous women - who don't seem to be returning to Iran after a long exile, but rather after a short shopping trip in Istanbul or other European destinations. By the way, you did expect the beauty of these women. Must be the coloring, or the cheekbones, or the way those eyebrows arch: once again, you feel inadequate and mousy in comparison.

It's your turn at the passport control window. The three-day-bearded official is young and surprisingly pleasant. He checks your passport and in less time and with fewer questions than it would have taken you at the Kennedy airport, he waves you on. You have to conquer one more passport checkpoint (you don't know why) but that takes even less time. Your bags - the souvenirs and your personal effects - have thankfully arrived and you strap them to the hand-cart you had bought and brought just in case but which you really won't need as there is an abundance of luggage carts around.

Finally, you are facing the legendary green and red customs lines. You are quite well-versed about what goes on here and you firmly head toward the green line. The man sitting at the entrance of the green line waves you (and three other travelers) over to the red line. The red line is populated insanely with multitudes of angry travelers who have just arrived from Damascus and Dubai and seem to have brought 16 suitcases and a kitchen sink per person, all to be searched in the red line.

The sight inspires enough despair and courage in you that you overcome your loathing for bargaining (and all the well-meaning advice about keeping a low profile) and you ask the guardian at the green line "Aqa, do I have to go through the red line even if I haven't been in Iran in 12 years?" and by God, there is a miracle. He has you fill out a form, and in less than five minutes you are approaching the crush of joyous loud relatives pressing against the windows, each other, and the railings to greet their travelers... and there is your favorite uncle - not much older than you remember him - grabbing you, grabbing your bags, and dragging you through the masses outside to the city of Tehran after 12 years...

End of part one: Part

two -- Part

three

Related links

* Also by Laleh Khalili:

- Loving

an Iranian man

* Features

* Travelers

* Cover stories

* Who's

who

* Bookstore

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved. May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

|

|

|

|