The Lost Legend

by Nazy Kaviani

14-Feb-2008

Three thousand people watched the New York City Ballet performance every night, a performance which invariably ended in standing ovations and a crowd that simply did not want to leave the packed New York State Theater. The promising young ballet dancer took his bows, with each bow intensifying the crowd’s applause and noises of approval and adoration, singling him out as “The Star” of the show.

* Photos [1]

* Video "Afternoon of the Faun [2]"

He was born to a family of artists, poets and writers in 1961. Afshin Mofid was one of two children born to the legendary Bijan Mofid [3] and his wife, Farideh Fardjam [4], the first female Iranian playwright, prize-winning author, poet, and director. He started ballet training in Tehran when he was nine years old, moving to New York to attend School of American Ballet [5], becoming the star of New York City Ballet [6] under George Balanchine [7]’s training and direction, and appearing as the star of the New York City Ballet on numerous occasions, nightly packing adoring crowds in the New York State Theater.

While his career and his sensitive and powerful performances in New York City Ballet’s productions were copiously covered in The New York Times and trade publications of note, we never knew about him. It is now time to know about the multi-dimensional and fascinating life of a man with not just one, but hundreds of stories to tell of himself and his accomplished and interesting life.

Afshin Mofid is one of the warmest, most down-to-earth people you would know. He speaks a perfect Farsi, devoid of English words, is affable, articulate, and very funny. He speaks honestly about his achievements, his decisions, his family, his good times and his bad.

"I was nine when I started Ballet in Tehran. I had never seen ballet before in my life. My uncle, Ardavan Mofid [8], was friends with Bijan Kalantari [9], who was a ballet dancer and a choreographer himself, and wanted to start the first Iranian ballet company from ground up, entirely with Iranian dancers, hoping to be able to perform internationally. Of the 14 students in the newly founded ballet program at Tehran's Music Conservatory (Honarestan-e-Ali-e-Moosighi), there were 12 girls and only two boys. I was one of them."

He started attending the Conservatory with his aunt, Hengameh Mofid [10], who went on to become a famous stage actor and director, and his uncle, Houman Mofid, who played the unforgettable role of Agha Moosheh in Bijan Mofid’s City of Tales (Shahr-e-Ghesseh) [11].

Living with his grandparents, his paternal grandfather, the late Gholamhossein Mofid, a teacher, an actor, the innovator and director of Shahnameh plays (Teatr-e-hemasi), an expert in Shahnameh recitation (Naghali), a calligrapher, and an avid sportsman and hunter, became Afshin’s role model. Afshin’s best times were spent hiking and hunting with his grandfather. When he was advised to stay away from football, hiking, and any physical activities which might lead to injuries threatening his ballet career, Afshin was resentful, telling his father that he wished to quit ballet school, and each year at his father’s urging and insistence, he would go back to a higher class at the Conservatory.

In 1977 when he was only 16, on Bijan Kalantari’s urging, his father sent him to New York to attend school and to learn ballet on an international level. Staying with Bijan Kalantari for the first several months, he was attending high school during the day and open ballet classes in the afternoons. He talks about his early years in New York with sweet sadness. With Iran on the brink of a revolution, his small scholarship covering only a cockroach-infested small room in New York City with salsa-playing Peurto Rican neighbors, he was homesick for Iran and for his family.

Afshin auditioned for School of American Ballet in 1978 and was admitted. The prestigious ballet school founded by George Balanchine, the neo-classical ballet legend and Lincoln Kirstein [12], the New York cultural giant, was the academy established to train and recruit ballet dancers for New York City Ballet. He says:

"Balanchine used to come to the school to watch the dancers dance during practices, and pick new dancers to join the corps de ballet as apprentices in New York City Ballet Company. The day he came to see us practice was a very exciting day. I was practicing, but in my own stubborn way, each time I messed up a move, I would stop the move and start all over again. He was there for a few hours and left. When our class was over, as I got dressed and picked up my backpack to go home, I was stopped in the hallway by Nathalie Gleboff [13], the school Associate Director, who told me 'Afshin, wait, I want to talk to you.’ She told me Balanchine had selected me. My stomach fluttered. I wanted to be so good to prove myself. Bijan Kalantari always said 'Dance well, not caring which company you go with. If you are good, a lot of doors are opened for you.' The New York City Ballet was top of the line, one of the best in the world. I was so happy I called Bijan Kalantari and my father to give them the good news."

"I showed up to my first practice class with George Balanchine. I had to stay way in the back of the room, where apprentices stood, with soloists and principals in the front. That first day when he arrived, he asked: 'Where is the Persian boy?' and everyone made way for me to the front of the room, where he asked me to do the move, and when I did it, he said ‘Very good. Very good.’ This became a pattern, a habit which would enable me to take attention, lessons and direction from Balanchine, offering me the privilege to be singled out to demonstrate to the ballet master."

During the Iranian Revolution, life became very hard for Afshin, as it did for many other Iranian students living in the US. His scholarship payments stopped, leaving him with almost no money with which to feed himself. He says for many months he sustained himself on a loaf of bread and a small container of orange juice at mealtimes. He also received a letter in the mail from Iranian government, asking him to explain what he was doing in the US.

With the help of Lincoln Kirstein, Afshin received a scholarship from School of American Ballet for both his day school and his tuition in the Academy, though he still showed up to practice famished and unable to afford anything else, as yet unable to participate in performances onstage because he didn’t have a work permit. When the hostage situation broke out and Iranian visa applications were frozen in INS, with the help of Alexander Papamarkou [14], the President of E. F. Hutton, his case was reviewed and his work permit was issued, so he could start performing onstage. “I was on Cloud Nine,” he says.

Afshin Mofid became one of the lead dancers in many New York City Ballet performances, from The Four Temperaments [15] to Divertimento 15 [16], to La Valse [17], to Goldberg Variations [18], and Nutcracker [19]. The most memorable part he danced, however, was the principal role in Afternoon of a Faun [20], originally choreographed by Valsav Nijinsky [21], on Claude Debussy’s exquisite music based on Stefan Malarme’s poem. For the duration of the time Afshin stayed at the New York City Ballet, no other dancer was ever allowed to dance that part. It was his and his alone. The New York Times wrote about his performance in May, 1982:

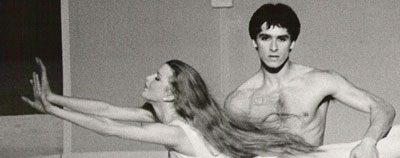

"Darci Kistler and Afshin Mofid, who danced it Saturday afternoon with the New York City Ballet at the New York State Theater, are currently its youngest pair. They give a wonderfully bold, even dramatic performance--one that peaks, as it should, and then subsides. Unlike many others, they do not reach for mystery, but look very real.

Mr. Robbins’s brilliant conceit was to transform the original faun and his nymph into contemporary dancers in a studio. And in this case, the matter-of-factness with which Mr. Mofid and Miss Kistler engage in their partnering makes them credible as dancers just as it brings into relief their few moments of emotional contact at the end. Miss Kistler gives us the all-American nymph—she relishes every movement, and her openness contrasts with the coiled-spring youthful sensuousness of Mr. Mofid’s portrayal. It is he who is the most affected. The moment when the man arches for the second time came across as deep. Mr. Mofid stood still after a partnering encounter and then allowed his body to take over."

Mofid says of his association with George Balanchine: “I wasn’t taking it for granted. Everyone in the group knew that this was an era about to close, every second was important, because Balanchine was 79 years old and ailing.”

In 1983 George Balanchine passed away and Peter Martin (New York City Ballet’s current Director) took over. The new era marked a significant void in the Ballet’s life and operations. Nobody could replace Balanchine successfully after 50 years, and the Company was dwindling if not in performance, in spirit. “Balanchine always gave feedback about performances. After he died, no one seemed to be in charge, we never got any feedback, so we weren’t getting developed. We would finish our performances every night and go home. We could all feel the void, the end of an era.”

That year after Balanchine’s death was a sad year for Afshin; a year that became increasingly difficult with a visit with his father, Bijan Mofid, whose illness had progressed and whose spirits had taken a major setback.

"The last time I saw my father in New York, he was a broken man, a lost little bird. I didn’t know how to face this situation. He came to New York, knowing he was sick and that he wouldn’t make it and said goodbye to me. When he died in 1984, at first the emotions in me didn’t really have a way to manifest themselves. I didn’t verbalize or express my emotions, but a year later they caught up with me."

"Remember I told you how when I was a child, I didn’t want to do ballet, but my father kept talking me into it? When he died, a big weight was lifted off my shoulders. I realized that I had done it for him. When he wasn’t there anymore, I felt I couldn’t do it anymore. There was no one left to please. I could do anything else I wanted to do. It was liberating and horrible at the same time. It was all I had done all my life between the ages of 9 and 26. Ballet had been my life, spending my life in a ballet studio. I was depressed. It was a bad time--Balanchine’s and my father’s deaths, one of the Company dancers had committed suicide, my girlfriend got hooked on Valium. I am not the type to use drugs when I am depressed. I had nothing to numb me out and felt everything full force. I couldn’t go on stage. When I did, I didn’t enjoy it. It was a dark time in my life and in my career."

Afshin Mofid decided one day not to return. He had had surgery on his knee, but he could still dance. Psychologically, though, he couldn’t dance anymore. He says:

"Many things played into one another. Maybe someone else who knew how to handle things would have done better. I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t verbalize anything, I didn’t cry for a year after my father’s death. When he died, after a year I became a feeling man. Accepting my father’s death, I became a complete man and I was able to feel and I was able to make decisions. Though we were distanced from each other physically, he had a very strong psychological hold on me. I didn’t know how to handle the situation. It took a toll on me. I didn’t know what to do. I wanted to enjoy life. The pressure in New York City Ballet was immense. My mother asked me what I wanted to do. I said I wanted to go into nature. Since my childhood I had known only two joys in my life, one was being out in the nature with my grandfather where I had a sense of freedom in my surroundings. The other was ballet which had proven to be very restrictive.”

At the end of this chapter of his life, ending ballet, the only thing he wanted to do was to go to the mountains and be in a beautiful natural environment. He called a dude ranch in Hamilton, Montana, where they taught attendees how to become hunting guides. The setup offered living on a ranch for two months, learning about horses, horse wrangling, horseshoeing, and packing horses and mules. When the two months were up, he knew he didn’t want to go back to New York. He felt that all his life he had been a slave to his art. He considered teaching ballet at the University of Montana, with ballet becoming just a job to enable him to be close to that awesome natural beauty, looking for his peace of mind. There were no jobs in Montana, but they put him in touch with someone at the University of Idaho, where they were looking for a ballet instructor. He had never seen Idaho, but took the job on the phone.

He returned to New York to pick up his things, say goodbye to his girlfriend, and go to live in Idaho. From dancing onstage where all those adoring fans went to see him perform every night in New York, Mofid became an anonymous person in Moscow, Idaho. He was getting paid very little, but had to work only 7-10 hours per week, with the rest of his week all to himself. He says:

"I bought my first car; I got my first dog, things I had always wanted to do, camping, fishing. I met lots of rednecks in the middle of mountains who knew nothing about ballet, Iran, or anything that had mattered to me. People wondered why I had left New York for Idaho. If I didn’t feel comfortable with them, I told them I was a PE instructor. In the middle of the forest one time, I met a man who became my friend and fishing partner. He was Jack Hemingway [22], son of Ernest Hemingway, a man in his late 60’s—we laughed about the twist of fate which would bring children of authors from different parts of the world to meet each other in the middle of a forest in Idaho!"

Afshin’s life as an outdoorsman took him to Sun Valley, Idaho, for a while. He was 28 years old by this time. He felt he had fulfilled his need to be with nature. He was still young, trying to get to know himself. He says as a ballet dancer, he had lived a very protected life, having always felt the need to have a life of his own. He had accomplished that with his four years in the nature, and he was ready to move on. Briefly, he contemplated going back to dancing. He even interviewed with the Pacific Northwest Ballet Company [23] in Seattle, auditioned, and was offered a contract. But he couldn’t see himself in a dance company anymore. He says:

"I went to Los Angeles. I had a friend there and my uncle, Ardavan, was there. It was so different from Boise or even New York, because there were many Iranians there, and my environment had completely changed. I wanted to go to school, and was looking for something else to do. I had always earned my living in ballet. I had always thought I didn’t have the ability to do anything else. So, I decided to try something new. In Venice Beach, I applied for a job as a waiter and got started the next Saturday night; I had no idea how to do it! I was so enjoying myself that first night, reminding myself that I was doing something other than dance; I was so pleased with myself, being a waiter! When that night ended, I felt so good about myself. A few nights later, I was recognized by a customer. She called my name and asked me why I had left the New York City Ballet.”

Afshin started teaching ballet at UC Irvine to support himself, worked in that restaurant, and started attending college. He had never attended college and had never been a good student academically. He had never paid attention to his education, because ballet had been his whole life. He started with one class, then two, and then a math class, and soon he started feeling more comfortable, completing all his undergraduate requirements. He then had to decide what he wanted to do after college. He wanted to have a job which would let him go anywhere he wanted to go. Afshin recalled his good experience with chiropractic since he had been a dancer and his back had been hurt, and looked into professional training as a chiropractor. He attended Los Angeles College of Chiropractic and graduated and passed Board licensing requirements. To support himself, he was performing in Nutcracker ballet performances in small companies, and had a small dancing part in a movie. He returned to Idaho whose nature he loved and started to work as a chiropractor. A couple of years ago, he started his own practice which is now doing very well.

From his beginnings in the arms of a family of accomplished contemporary Iranian cultural and artistic figures, to his ballet school days training side by side with legendary dancers such as Rudolf Nureyev [24] and Mikhail Baryshnikov [25], to his stellar success on the stage of Lincoln Center Theater performing nightly for thousands, to his days wandering the nature and finding himself, to today where Dr. Afshin Mofid is a well-known professional in his community, nothing seems to have affected or decreased the charm, the joy of life, and the quest for happiness in this extraordinary Iranian. He is an Iranian whose life’s story and news was lost to us for three decades, but whose love and interest for Iran was never lost, staying with him wherever he went.

Afshin Mofid says though he only tells some of his patients about his previous career as a ballet dancer, occasionally he gets patients who would say: “We tried to look you up on the internet, and all we got was this other guy with the same name as yours--a New York City Ballet dancer!” Little that they know, he was and continues to be all that and a lot more.

* Photos [26]

* Video "Afternoon of the Faun [27]"

Visit nazykaviani.blogspot.com [28]

| Recently by Nazy Kaviani | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Baroun | 3 | Nov 22, 2012 |

| Dark & Cold | - | Sep 14, 2012 |

| Talking Walls | 3 | Sep 07, 2012 |