While Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was touring the UN last week, delivering acerbic speeches and giving interviews, back home in the Iranian parliament questions were raised not about Ahmadinejad himself, but about the institution of the presidency in total, and whether there is a need for a president alongside the Supreme Leader’s office.

On September 20, Parliamentary Deputy Hamid-Reza Katouzian announced that “some [prominent] political analysts are pondering the lack of necessity for a president in a country like Iran blessed with velayat-e faqih (supreme clerical rule) and a great leader [like Ayatollah Khamenei].” According to Katouzian, the idea is to do away with the office of the president, and to create a parliamentary system where the parliament would choose the prime minister. This may seem surprising, but in fact is in line with the incessant calls by the IRGC and the conservative camp for the absolute rule of Khamenei as the sole ruler of the country. The Supreme Leader himself amplified this new movement recently by interpreting the meaning of the constitutional term “absolute rule of the faqih” as a flexible definition, which allows for ever-increasing role of the faqih “in new realms.”

These new concerted efforts shed light on the cause of continuous disagreements that have existed between the Supreme Leader and the three presidents of the Islamic Republic since he took office. To wit, Rafsanjani was accused of being corrupt; Khatami was accused of succumbing to the West, and later as being close to the “seditious” ring; and Ahmadinejad is purportedly connected to the “deviant” circle, bent on dismantling the institution of Vali Faqih. It is likely that those presidents have not been good enough for Khamenei because of his grand design to do away with the institution of the presidency altogether, and to put an end the dual rule by an elected president and an unelected Vali.

It is unlikely the office of president will disappear by the next election in 2013, when Ahmadinejad’s term expires. However, in this revisionist model, the parliament will be in charge of choosing the prime minister. It is likely that Ayatollah Khamenei had this in mind when he “complained” in April about the lack of discipline in the parliament. Taking a leaf out of Chairman Mao’s Red Book, the Ayatollah argued that the legislative body that supervises the nation needs to be supervised itself. Dominated by arch conservatives, mostly former members of the IRGC, the parliament followed suit, and voted for a new internal regulation for self-censorship.

The regulation stipulates five punishable offenses for the deputies, the third of which is “Breaching national security, and conducting [unlawful] clandestine activities as defined by the law enforcement [officials].” These are code words for voicing opposition. This regulation paved the way for “legal” interference of the Judiciary in the legislative body and the arrest of parliament deputies for their words and deeds. This new regulatory procedure curtails the remaining freedom of speech of the deputies, and slyly overrides article 86 of the Constitution that gives them immunity from persecution for their speeches made in the parliament. By assigning the role of choosing the prime minister to such a parliament, which is already enfeebled by the vetting power of the Guardian Council (itself selected directly and indirectly by the Supreme Leader), there will be no other voices in the country but the one coming out of the Supreme Leader.

Dissolution of the Plan and Budget Organization that took place in the first term of the Ahmadinejad presidency was possibly another step to do away with any form of supervisory institution in the country. The Supreme Leader probably hatched the idea when the sixth parliament, dominated by the reformists such as Ali-Akbar Mousavi- Khoeini, demanded transparency from the large endowments under the Supreme Leader’s office. Khamenei could thwart that effort at the time, and the idea was buried in the seventh parliament, which convened with a majority of conservative deputies.

Formation of a different state?

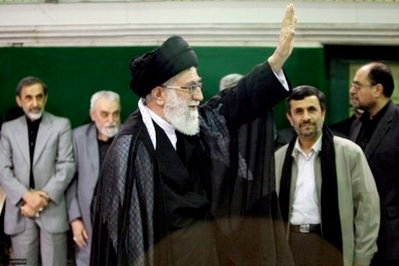

A radio station asked me some time ago about Ayatollah Khamenei’s vision of an ideal state. The reporter said that Khamenei does not get along with any president. What is he looking for? What kind of state does he have in mind? I answered that the ideal state for Ayatollah Khamenei is already in place, and that is his Beit or office. What the reformists used to allude to metaphorically as “the shadow government” now is the real government. Prominent members of the Supreme Leader’s office, such as Seyed Ali-Asghar Hejazi, Vahid Haghani, Mohammad Mohammadi-Golpaygani, Ali-Akbar Velayati, Yahya Rahim-Safavi, Mohammad-Ali Aziz-Jafari, Qassem Soleimani, and a subset of members from various security and military forces and religious commissars are now running the country by decree.

The statement by the parliament deputy Katouzian may be the harbinger of what Ali-Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani and Mir-Hussein Mousavi’s warned about right after the 2009 election debacle. They said that plots were hatched to build a “different state,” replacing the present Islamic regime. Probably they were alluding to this new state, a military-clerical state where Vali takes off his cloak to dun his old military fatigues he wore so proudly during the war against Iraq. Ayatollah Khamenei cut his teeth in the war front as the informal deputy commander of unconventional warfare. He has more military and security experiences than ecclesiastical studies. In the matters of war and security, Khamenei is probably more seasoned than many IRGC leaders.

The imagined new regime, led by the military-clerical Supreme Leader Khamenei will continue to take advantage of Shiite lore as an effective means of creating solidarity in the ranks, spreading fear in the name of religion, and using the knowledge of performing religious rituals as the litmus test for gauging loyalty to the regime. While the IRGC members, retired or active duty, run the state, the government will showcase a prime minister and a cabinet drafted by the subdued parliament. But two hurdles remain: The name of the Islamic Republic needs to be changed to reflect the removal of presidency, and a referendum has to be held to change the Constitution.

Changing the country’s name after just 32 years since the last name change is odd, but African countries do the same often with no major problem, except for some international confusion.

Removing the office of presidency by a plebiscite may prove to be more problematic: The last revision of the Constitution was put to referendum in 1988 coinciding with the transition of power from Ayatollah Khomeini to Khamenei. It removed the office of prime minister, among other changes. Then the war weary Iranians paid not much attention to the grave changes that were being made which largely changed the nature of the law.

This time may prove to be different. Iran’s urban dwellers have sought various opportunities in recent years to show their resentment. A push toward constitutional amendment with the clear intention of enhancing the Leader’s power may prove to be not that easy; and it could provoke another large scale and potentially destructive mobilization against the regime.

First published in insideiran.org.

AUTHOR

Rasool Nafisi, a professor at Strayer University, is a specialist in Iranian politics and the clerical establishment.