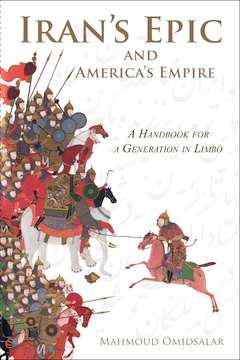

Following a brief survey of Iranian history from its beginning in the 7th century B.C. to Ferdowsi s time in the 11th century, Mahmoud Omidsalar’s Iran’s Epic and America’s Empire (Afshar Publishing, 2012) provides a history of the poem and a biography of its author. It offers an explanation of the Shahnameh as a national icon and considers the implications of the poem for the present political tensions that mark Iran’s relationship with the West.Mahmoud Omidsalar obtained his Ph.D. in Persian Literature from the Department of Near Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley, where he also studied Folklore under Alan Dundes. In addition to publishing many essays on Persian literature and folklore, he has also edited the 6th volume of the new critical edition of the Shahnameh, under the general editorship of Professors Khaleghi-Motlagh and Ehsan Yarshater.

PREFACE

What follows is a meditation on Iran’s national epic. It is addressed to the Iranian community abroad, and more importantly to that community’s children, many of whom don’t speak or read Persian but think of themselves as Iranian. This is an old man’s gift to the young in order to help them seize that chain of memory which makes us one people. It is an exhortation to remembrance because human beings are made of memories; recollections of events that happened and also of those that did not. Mankind achieves its humanity and its community in its real and imagined memories, and for us Iranians, the Shāhnāmeh is the highest poetic expression of that communal remembrance that connects us to one another and anchors our present to a shared sense of the past. It links us to a time of myth and legend that exclusively belongs to us, and to the land that we have inhabited for the past three thousand years. If Iran is our Jerusalem, a place of unrelenting longing in our soul, and if Persian literature is our Torah, then in that Torah, the Shāhnāmeh is our Psalms. For these reasons and a thousand others no Persian can say anything “impersonal” about the Shāhnāmeh and no “other” can say anything about it that is not taken personally.

To the extent that the Shāhnāmeh is Iran’s national epic as well as her “ethnic history,” all scholarship on the Shāhnāmeh is by nature a comment on Iranian nationhood and ethnicity. In these disordered times when lies are routinely passed off as truth, and when descendents of those whom our ancestors freed from their Babylonian bondage can presume to threaten us with “preemptive” military strikes and nuclear extinction, the lines have been drawn very clearly.[1] A poem about wars and heroic combat becomes itself a battlefield, a place of confrontation between Persians and those who encroach on the Iranians’ sense of self. This is not a time for weakness, for compromise, or for pseudo-civility. There is nothing civil in military threats.

What I intend to do in this small volume is to walk my countrymen through a brief history of our culture and through all that led to our national poet, Ferdowsi, and to our national poem, the Shāhnāmeh. Along the way, I hope to disabuse my readers of a number of dangerous myths that have been inculcated by our relatively recent experience with Western colonialism. Following the introductory chapters that briefly deal with Iran’s cultural and political biography, I will take up the relationship between our language and our ethnicity as understood by the general public, and not a few scholars. Drawing upon what we have learned in our brief review of Iran’s history, I will challenge some of the prevailing “truisms” about Persian language and literature, and will show how many of these “truisms” are not merely wrong but border on the strange.

There is a biographical chapter, which is devoted to a consideration of Ferdowsi and his social and cultural milieu. In it, I will tell you that our national poet was not only a great artist, but also a conflicted man often at the mercy of his prodigious appetites and psychological forces that dragged him to and fro. The story of our national history and how it evolved into its present form is told in the next chapter. The final two chapters discuss our relationship to the Shāhnāmeh as the embodiment of our nationhood.

In a lecture entitled “The Hero as Poet,” and delivered in 1840, Thomas Carlyle (1795 – 1881) addressed the heroic nature of great poets.[i] Ferdowsi is a heroic poet for us. We already admire and revere him as a hero and as a cultural icon. I will suggest that we must also sympathize with him for the tragic figure that he was. In the final chapter, I attempt a synthesis of these studies and speculate on what they may mean for Iranians in the strange world which we inhabit along with Guantanamo detainees and prisoners of the Gazan Ghetto: western civilization’s latest “gifts” to the orient.

NOTE

[1] 2 Chronicles 36:22 – 23: Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of the Lord by the mouth of Jeremiah might be accomplished, the Lord stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom and also put it in writing: “Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may the Lord his God be with him. Let him go up.” Cf. also Ezra 1:2, 5:2, etc.