Interviewer: Bernard Gwertzman, Consulting Editor, CFR.org. Interviewee: Richard N. Hass, , President, Council on Foreign Relations.

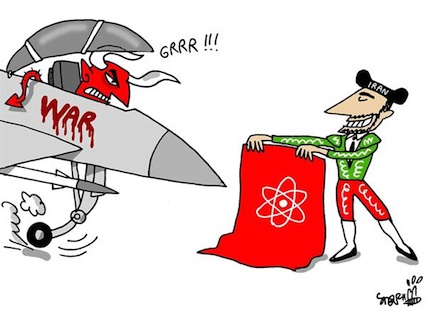

Given that diplomacy to end Iran’s nuclear program has “come up empty,” Richard N. Haass, a veteran Middle East expert, says that he takes Israeli talk of a possible preventive attack “at face value.” He says the United States has tried to calm the Israelis, but “one of the many unknowns is whether any degree of U.S. reassurance can persuade the Israelis, given what the Israelis see as the stakes.” Overall, he says, this is a situation where there are no obvious or easy choices, and while a nuclear-armed Iran presents “a terrible outcome strategically,” a U.S. or Israeli military attack carries unforeseeable risks.

Over the summer, there have been very strong statements from Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Ehud Barak about the strong possibility of Israel launching a preemptive attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, since the diplomacy to stop Iran’s nuclear program hasn’t worked. What should be the U.S. reaction?

I take the Israelis at face value here. They are genuinely concerned, given that the Iranian nuclear program continues to progress both in terms of quantity and quality. The negotiations–or the “diplomacy,” to use a better word–have so far come up empty. This is all done against a backdrop where, for the Israelis, it is extraordinarily difficult politically and psychologically to franchise out their foreign policy, be it to the United States or anyone else. So when you meet Israeli officials, one of the first questions on their minds is not simply who is likely to win the American elections, but, “Do you think either President Obama or a President Romney would ever be willing to undertake a preventive military strike against the Iranian nuclear program?”

Do you think the Israelis would like the United States to strike Iran?

My reading is the Israelis would prefer that the United States do it because they understand that we have a greater military capacity. They also understand the regional politics would be somewhat less hostile if the United States does it instead of Israel. But they have a degree of doubt. The best thing for the United States to do is try to reassure the Israelis. The administration has tried sending senior official after senior official, apparently sharing to a large degree U.S. planning, to impress the Israelis that the United States takes this threat seriously. At the end of the day, though, one of the many unknowns is whether any degree of U.S. reassurance can persuade the Israelis, given what the Israelis see as the stakes.

Some experts have suggested that despite the election campaign, President Obama should make a trip to Israel to reassure the Israelis, since he did not visit Israel during his term. What are your thoughts?

That sort of trip would be open to all sorts of interpretation and speculation. My own sense is it’s unlikely to happen, and I’m not sure it should happen at this late date. It’s always a risk to insert national security in the midst of a political campaign, and whether it was fair or not, it would be interpreted in political terms. If the president wants to send certain messages to the government of Israel or any other government, he has the means to do it. That’s why envoys were invented, be they permanently stationed ambassadors or those who are dispatched. The bottom line here is that no one should dismiss the possibility that Israel would undertake a preventive strike sometime this fall before the American election. If that were not to happen, then the possibility of either an Israeli or an American action in 2013 is quite real.

How does the Non-Aligned Movement summit, which is taking place this week in Tehran, figure into the discussion on Iran?

Why there even is a Non-Aligned Movement anymore is high on my list of puzzling features of the foreign policy business I’m involved with. Strategic alignment ended a generation ago in 1989 when the Berlin Wall came down, so I’m not entirely sure who those who declare themselves non-aligned are non-aligned against. Or who are they non-aligned with? It’s an anachronism. And secondly, when one looks at who’s there, a lot of it is simply a collection of the people who are on the wrong side, if you will, of the international tracks, people like Hugo Chavez, president of Venezuela, and obviously the host government of Iran, Robert Mugabe from Zimbabwe, and so forth.

What’s disappointing is you have people also like the Indian prime minister and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon attending. No one should lend any legitimacy to a gathering convened in Tehran by this Iranian leadership in the name of non-alignment. It sends exactly the wrong message. We should be doing everything possible to isolate this Iranian leadership for its nuclear program, but also for what it’s doing in Syria to facilitate the repression there.

Is there any possibility that the Secretary General can work out anything with the Iranians on this trip?

Diplomacy isn’t always in the cards. Years ago I wrote a book (Conflicts Unending: The United States and Regional Disputes) about ripeness and about the need for certain preconditions to be in place in order for diplomacy to have a chance of prospering, and on either issue in the short run, I don’t see much of a chance.

In Syria, the only chance for diplomacy will come when the regime is on its last legs, and then perhaps one could facilitate the exit of President Bashar al-Assad and his regime. With Iran and the nuclear program, I’ve not given up on diplomacy, and I still think there’s a chance down the road that you could come up with an outcome that would be enough for the Iranian government to wrap themselves in, but would not be too much for the United States or Israel or the rest of the world to accept. But that would really be threading the needle. I would say it’s a possibility, but it’s going to be extraordinarily difficult to come up with that sort of a negotiated outcome.

What are the options? Some people have suggested a deal could be struck if we made an explicit offer to guarantee Iran’s peaceful use of nuclear material.

There’s lots of things you could do: You could guarantee certain types of access, not to the ingredients, if you will, or the material, but assurance, as you put it, about access to nuclear power. You could promise certain types of sanctions relief. But essentially, Iran would have to get out of the enrichment business or the business of the storage of enriched material. I don’t know if that is something they would be prepared to accept.

The goal here should not be to humiliate Iran. The goal here should be to make sure that Iran is not allowed to keep in place the prerequisites of a nuclear weapon that could be assembled in short order. Whether you could square this circle, come up with something that the Iranians believe is not humiliating, but also come up with something that the rest of the world would feel is reassuring, I don’t know.

Do you think that the Israelis also feel a bit under pressure because of the change in the leadership in Egypt in particular?

Well, strategically, the last year and a half has been an extraordinarily worrisome set of events for Israel. You not only have the Iranian threat, but on Israel’s borders you’ve had the obvious deterioration in Egypt and in Syria; Lebanon was already bad, and Jordan’s future is a source of recurring uncertainty and concern for the Israelis. And all of this is in addition to the absence of progress on the Palestinian front. So quite honestly, the Israeli strategic situation, I would say, has deteriorated over the last eighteen or so months because some of the positive features of the post-1967 strategic map can no longer be assured.

And of course, Mohamed Morsi, the new president of Egypt, is about to visit Tehran for the NAM meeting.

The mere fact that he may visit Iran is a worrisome development. But even more worrisome is the consolidation of his domestic political power at home and the fact that he might be in a position to dominate or at least heavily influence those who would be in a position to write the new Egyptian constitution. Constitutions, in some ways, form the foundation stones of a democratic system, and that is an issue of real concern: the potential for majoritarianism, where minority and individual rights become vulnerable to the majority, the potential absence of meaningful checks and balances. These are all legitimate concerns.

Let me just come back to where we started. If Israel did attack Iran on its own, what would be the repercussions?

So much depends, if that were to happen, on how the Iranians would choose to retaliate, and that’s where the United States comes in. If Israel were to undertake a preventive strike, then I believe the United States very quickly should signal to the Iranians that they do not have in any way whatsoever a free hand in retaliation–that Iran should understand that by what it does, it risks bringing in the United States directly, and that it risks escalating the conflict in ways that would bring a much broader range of Iranian targets and interests into play. So again, if Israel makes the decision to act, I would argue the United States then needs to position itself so it could try to influence the trajectory of the crisis moving forward.

Several Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, have been urging the United States for some years now to attack Iran, but of course they would be compelled to criticize the Israelis if they attacked Iran.

One of the reasons I think even the Israelis would say that it’s preferable that if an attack were undertaken it be done by the United States is that they would face less regional repercussions. The question is not so much what governments say beforehand, it’s what they say and do afterward, and we’d have to see, particularly in this new political environment, what would be the reaction of people in these countries.

One of the enduring results of the upheavals in the Arab world is the political mobilization of the Arab people. Governments now have to contend much more with their own people and their political voice than ever before, so even if governments for strategic reasons would like to see Iran attacked, it’s not necessarily clear to me that that stance is shared by their broader public. It’s one of the many unknowns. You begin not only with the unknown of whether something will happen, but what would be the immediate results, in terms of what was actually destroyed. And then there’s the question of the direct and indirect repercussions. This is one of those situations where there are no obvious or easy choices.

Living with an Iran that had nuclear weapons or got close to them, I believe, would be a terrible outcome strategically, but using military force, be it by Israel or the United States–we shouldn’t kid ourselves–sets in motion a chain of events that we don’t know necessarily where it takes us. It’s why everybody, or at least why most people, are hoping that this combination of threat and economic sanctions and diplomacy can succeed. But so far, at least, there’s not great grounds for optimism.