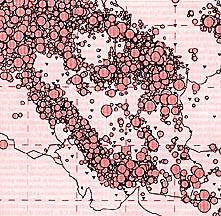

Seismicity map of Iran.

Larger circles mark greater intensity.

Sign of injustice

By Xavier de Planhol

Encyclopaedia Iranica

Sources and state of current knowledge

Based on numerous but fragmentary observations of earthquakes over

a long period of time, it is only since the middle of the 20th century

that there has been an attempt at systematic study of seismic activity

in Persia and that macroseismic data collected at international stations

have been refined in relation to the Persian situation, through the establishment

of a network of local seismological stations, in Tehran (1958); Shiraz

(1959); Safidrud (1962); Tabriz, Mashhad, and Kermanshah (1964-65); Bushehr

(1975); Isfahan (1976); and Sava (1977), each the center of a constellation

of substations.

After early, incomplete, and imperfect attempts at cataloguing earthquakes

in Persia, the first comprehensive seismotectonic map of the country was

published; it was limited to north central Persia and was drawn to a scale

of 1:1 million. It was soon followed by a map of the entire country, drawn

to a scale of 1:2.5 million, with supplementary maps of the epicenters

of estructive earthquakes in the period 1900-76, of the principal faults

in the country, and of earthquakes recorded

since the 4th century B.C.E., all drawn to a scale of 1:5 million.

The historical study was taken up again in a fundamental work by N. N. Ambraseys and Charles Melville (1982), who drew upon a much broader range of documentary sources; their work is a model of its kind, encompassing not only a general study, but also reconstructed maps of the areas of destruction connected with a number of major historical earthquakes. More recently these data have been integrated into a much less detailed synthesis and then into a general seismic map of the entire Near and Middle East.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that our knowledge of past earthquakes is still insufficient, owing particularly to the extreme unevenness of the documentation for different regions; indeed, for many sparsely populated desert areas it is almost entirely absent, both from textual sources and from the archeological record. The broad outlines of seismotectonics have thus been established, but they cannot yet be filled in without some hesitation and approximation.

General features of the seismological geology of Persia

The main relevant feature is the great Zagros fault line, where the

Arabian and central Iranian plates overlap. In this zone, 1,600 km long

and on average 250 km wide, seismic activity is extreme. Historical data

suggest that there has been continuous seismic activity, with occasional

local tremors, but chiefly a large number of mild earthquakes bearing little

relation to tectonic fractures in the region or to visible traces of recurrence;

nor can they be linked with major faults. In certain parts of the Zagros

nomadic tribes report that the earth trembles more or less regularly every

year, setting off notable rock slides.

At Bandar-e Abbas in 1622, besides a major earthquake on 4 October, there were six or seven minor tremors, but the residents reported to a European traveler that there was usually an average of only one earthquake a year. Altogether, however, this zone seems to have been relatively free from major earthquakes, and, despite continual deformation of the earth's crust, most episodes have had no serious seismic consequences.

Throughout its history Shiraz has experienced numerous tremors in which varying numbers of buildings have collapsed, but only one truly cataclysmic earthquake, that of 5 May1853, in which about 9,000 people died. Northeast of the Zagros central Persia corresponds broadly to a mosaic of Gondwanian plates, the details of which have not yet been sufficiently defined; altogether, they constitute a stable zone. Major earthquakes are rare there, and it is the region in which the largest number of early minarets are preserved (at Isfahan, Yazd, and Kerman; for Isfahan, see Ambraseys, 1979). Earthquakes there seem to be essentially local reverberations from major events in other regions.

Movements resulting from the subsidence of the Zagros are, however, transmitted through the central Iranian plates toward the northern and eastern zones, tracing a gigantic triangle. These northern and eastern zones thus experience the most intense seismic responses to the general drift of Arabia toward Eurasia. It is there that most serious earthquakes occur, throughout the length of the so-called Iranian Crescent, which extends from Azerbaijan through the Alborz, Khorasan and the Kopet Dag, Kuhestan, and Sistan east of the Dasht-e Lut as far as Makran, for which sources are rare.

Important earthquakes can also occur in the regions of central Persia

along the edges of the Iranian Crescent, thus in the Tabas (earthquake

of 16 September 1978, which left 6,300 dead, 3,600 in the town itself)

or in the fault area around Kashan (15 December 1778, in which more than

8,000 died).

This seismic activity between tectonic plates does not appear to depend

on the apparent surface tectonics or on the major Quaternary faults; rather

it is correlated with minor faults, tilted and sometimes very recent, that

have cut across earlier instances. Relatively long periods of quiescence

separate major paroxysms, which thus seem totally unpredictable. For example,

Nishapur was affected by serious cataclysms in 1209, 1270, 1405 (leaving

30,000 dead), and1673 but has remained almost free of earthquakes since.

Only Azerbaijan, particularly in the region of Tabriz, is distinguished by apparently continuous seismic activity. More or less severe shocks were experienced in the city in 858, 1042, 1273, 1304, 1345, 1459, 1550,1650, 1657, 1664, 1717, 1721, 1780, 1819, 1837, 1843,1856, 1896, and 1930; those of 1042, 1721, and 1780 were particularly destructive, each doubtless causing 20,000-50,000 deaths. It has been suggested that seismic activity alternates somewhat between the northern and eastern parts of Persia, the former seeming to be enjoying a period of relative calm at present (with the exception of the Rudbar earthquake in 1990), while the latter is undergoing a peak of activity.

Earthquakes in the beliefs and daily life of the Persians

In Persian popular belief the origins of earthquakes are attributed

to the position of the globe on the horns of a bull, itself resting on

a fish. When the bull is tired or, according to others, when there is too

much injustice in the world, he becomes impatient and shifts the globe

from one horn to the other, with resulting earthquakes. Some people claim

that earthquakes occur where the earth falls directly onto the bull's horn.

This notion is actually quite widespread all across the Islamic civilization of the Middle East, but Persian versions can be adduced, interpolation showing the influence of Shi'ism. The earthquake that destroyed Quchan in Khorasan in 1895 was explained by the fact that a son of the Imam Ali al-Reza, whose tomb is located there, had gone to visit his father, who is buried at Mashhad, thus leaving the city defenseless against the elements.

Recourse to astrologers was common during cataclysmic occurrences, and there were also individuals who predicted earthquakes. The astrologer Abu Taher Shirazi was reported to have predicted the exact date of the earthquake that destroyed Tabriz during the night of 3 October 1042 and killed more than 40,000 people. He was consequently chosen to direct the reconstruction of the city and announced that in the future Tabriz would no longer be in danger.

Hamd-Allah Mostawfi, writing in 1340, noted that the prediction had proved correct. After an earthquake at Urmia in 1300/1883 an astrologer from Tehran sent a telegram informing the population that the earth would continue to tremble for forty days. Armenian priests consulted their books and announced a new shock for the next morning at 11 o'clock. A mulla from Tabriz predicted an aftershock for the following Sunday at 2:00 p.m., which set off a panic among the population. As his prediction did not come true, the mulla was arrested.

On 28 May 1845, at about four hours before nightfall, a tremor was felt

2 parasangs (ca. 14 km) from Mashhad just at the place where the European

traveler J. P. Ferrier was preparing to camp

for the night; his guide concluded that the tremor was a bad omen and moved

the camp.

In such a situation of permanent danger it is paradoxical that no systematic adaptation of traditional Persian construction techniques to the frequency of earth tremors has been attempted, at least until very recently. After the great earthquake of 1780 at Tabriz the inhabitants began to build their walls as low as possible, using wood instead of brick and stucco, and to roof the bazaars with planks, rather than with domes. Nevertheless, in 1817 they again rebuilt the city walls to a considerable height.

In the same city it was apparently Westerners in the service of the crown prince Abbas Mirza who first introduced construction methods that provided a certain security, particularly wood-frame structures with flexible joints (known as takhta-push); while such methods seem to have been reserved for temporary shelters in gardens, the old houses were rebuilt in the traditional fashion.

After the earthquake of 1871 at Quchan a new type of emergency shelter appeared: beams removed from the ruins were assembled in "A" frames or used as ridge poles, the walls being plastered with earth. When such a house had to be enlarged, an identical building was constructed parallel to the first and the space between enclosed with walls and covered with a flat roof. Houses of this type, consisting of one to three rooms, withstood the earthquakes of 1893 and 1895 and were still in place in 1904. But these ephemeral improvements do not seem to have had any long-term impact. In the 1960s there were private attempts in the comfortable neighborhoods of northern Tehran to bring spherical houses, already ill-adapted to the sloping terrain, up to antiseismic standards, but no official regulations were ever adopted.

In fact, Persia, which includes some of the most seismically active regions in the world, seems never to have been seriously concerned about the danger and the need for preventive measures. Daily life is marked by indifference and appears not to have been noticeably affected by major episodes. The historical repercussions have been none the less significant, particularly for the fates of certain cities. The decline of Qumes in the 9th century, of Siraf in the 11th, and of Nishapur after the 12th-14th centuries seems to have been largely owing to destructive earthquakes.

Web

Site Design by: Multimedia

Internet Services, Inc. Send your Comments to: jj@iranian.com.

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved.

May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

Web

Site Design by: Multimedia

Internet Services, Inc. Send your Comments to: jj@iranian.com.

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved.

May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.