Blooming Blooming

Interview with film producer/director Aryana Farshad

By Brian Appleton

April 15, 2004

iranian.com

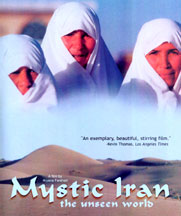

"Mystic

Iran, The Unseen World"

A film by Aryana Farshad

Beverly Hills, Ca.

Narrated by Shohreh Aghdashloo

The first time I met Aryana Farshad and her parents and her six

siblings in Tehran was in 1966 when I went for my initial visit

at the age of 16 to Iran. I had gone there to spend the summer

with her next-door neighbors and family friends, whose eldest son,

Touss Sepehr, was my school friend from boarding school in Rome. This interview was conducted this spring of 2004 over the course

of the past

six weeks with me tracking Aryana down by phone, mostly at 5 am, from my office

in San Jose, California to the studios in Beverly Hills to London to Paris

and back to Beverly Hills on the occasion of the first screening of her new

film in Europe under the sponsorship of the Iran Heritage Foundation.

Q: Aryana, I remember you quite clearly even though it

has been something like 36 years... crikey? How time flies! The

last

time I saw you (we were all young) I was 18 years old in Rome.

I went to dinner with you and your sister

Keyvan, Parvin Ansary (see my interview of Ms. Ansary called:

"The

last colony") and her niece Saideh at the Maiella Restaurant.

I

hadn't

thought of that till now. There were 7 women and me and I fought Iranian

style over who would pay the bill. I was the youngest but I insisted

on paying because

I was the only guy. Q: Aryana, I remember you quite clearly even though it

has been something like 36 years... crikey? How time flies! The

last

time I saw you (we were all young) I was 18 years old in Rome.

I went to dinner with you and your sister

Keyvan, Parvin Ansary (see my interview of Ms. Ansary called:

"The

last colony") and her niece Saideh at the Maiella Restaurant.

I

hadn't

thought of that till now. There were 7 women and me and I fought Iranian

style over who would pay the bill. I was the youngest but I insisted

on paying because

I was the only guy.

A: Whahhhhhh! I remember you. What a memory you have! Of course,

it was my sister Keyvan, Feri, Parvin, Saideh, myself, and two

other girl friends of

ours who went to dinner that night in Rome and you were the only young

man with us. Good old memories. Brian jan, you have to follow me

around by phone

for this interview since I will be leaving for London Feb 5th for a screening

and will be back in L.A. for another screening event March 8th for International

Women's Day! Lots of work to be done, empty handed, like the making of

the film and my life as a whole.

Q: Last time I saw you we had more of life ahead of us

than behind us and now we have more behind us than in front of

us. We were

both like clean

slates not knowing what we wanted to be yet. This keeps happening to

me lately.

Two

years ago I ran into Shohreh Aghdashlou in Cupertino, California after

23 years, back stage after her performance of "My Share of Father's House"

with

her husband Hushang Tozie.

The last time I had seen her was for a photo

shoot

in the garden of Touss Sepehr's yard next door to your family house

in Tehran. Don't you think it is odd that we should meet again

like this

after all these years and also why does it appear to be the year for

Iranian Women: Nobel Peace Prize, Miss World Canada, Miss Germany,

first woman

of Iranian descent in German parliament, Best Supporting Actress Oscar

nomination,

and

now your film! What is up? A: Life is a cycle. It is a rule of the universe... . You have

to finish what you have started; if you start some energy with

a person you have

to finish it with them, you have to finish your karma with everyone.

Karma is not only

a bad thing but good business too. We are bundles of energy which attract

each other... it is no mystery to me to run into old friends again

after all

these years and distance.

Regarding Iranian women rising to international stature, that

is not surprising to me either. First, it is not something that

happens over

night. As human

beings, we don't bloom over night. It took all of these incredible

women, years to come to the point of becoming successful in their

crafts and

it certainly comes from having strong faith and belief in what they

want to

do, what they

want to say and what their goal in life is. It requires dedication,

discipline, hard work, sacrifices and lots of pain. As Iranian women,

we initially

grew up in an open atmosphere in Iran or abroad.

When I lived in

Iran, we were

even more advanced than Western women, in many cases. If we get into

this, it will

be a long list and long story to tell. So it is not a surprise for

Iranian women to shine inside or outside Iran. Some of us were long

overdue,

like Shohreh, myself and many others who are shining and will shine

at an international

level.

In my case, I initially mastered my craft at a young age and was

already good at what I was doing and I was working at an international

level.

The revolution

postponed the process. We found ourselves in a different culture,

a different speed, and different thinking patterns. We had to

learn all

over and

adjust to the new life style and culture, which was very different

than ours.

So it took years to adjust, to learn and grow again. For me, it was

like going

inside,

into seclusion and solitude, evaluating my life, my abilities and

my goals and growing from the inside out. Along the road, there

were major

obstacles,

being a foreigner, being an Iranian, being a woman, having an accent,

the negative feeling of Americans toward Iranians, financial problems,

work

problems, proving

ourselves and mostly lack of support from society and being alone.

Many years ago, I was working at one film studio in Hollywood.

To be accepted, I had to work 3 times more than the others to prove

myself.

Once I was

told by a colleague "why don't you go back to where you belong?"

Well, as you know me, I don't accept these kinds of comments very

well. I

asked this colleague what was his origin? We found out that he

came

from an

immigrant family during WWII and hopefully he understood my situation.

Many times,

I was told to change my name and tell people that I was European

or Canadian, due to the nature of my accent (French speaking background)

and my look.

I

refused and instead, I rushed to Sherkat Ketab in Westwood and

purchased many books about Iran, some even very expensive, like

Bridge of Turquoise

and many

others. I took them to work or invited people to my home and educated

them about our history, culture, and life style. A grass roots

education, which

worked very well.

The pressure AND THE FALLS help you to bounce back stronger.

We all went through a rebirthing stage to become who we really

are

and who

we are

today.

Q: So who are you now after all these years?

A: As I mentioned, I am a late bloomer, but at least, I

think, I am blooming. I want to do many things in addition to making

documentary

films.

I want to

live, to experience, to travel, and meet different people from

different cultures and different life experiences and share it

with others,

in any

format, photographs,

books, documentary or feature films. The door to creativity is

one door. When the quest is truly from within, we can create what

we

want, from

intuition.

I have spent 25 years of solitude in

the USA, after the

revolution. I had to go into solitude in order to come back out,

in order to recreate

myself.

I woke up one day and realized that I had no country, no father,

no mother, and no help. At first I panicked and cried for days.

You have

to understand

that I grew up in a leisurely life style and very spoiled. Consequently

life was hard, very hard, but then I came to a conclusion: "I

have my health and myself... " I didn't allow myself the luxury

of depression, nor leisure... I went to work and worked hard, 14

hours a day and seven

days a week, and still do.

I take life as living in the moment and do my best, every day

to push forward. The rest, I can't predict it. Could you?

Q: Let us back up to the time before you came to the USA and

talk first about your childhood. I remember you had a large family

and

I remember

your parents

and your siblings, especially your two brothers. Who was the biggest

influence on you during childhood?

A: Dad was the biggest influence on me. I was very close to my

father. He was educated, honest, hard working and a giving man.

He dedicated

his life

to educate

the younger generations for 60 long years. He loved his country

and would sacrifice for it. I use to wait up till midnight for

him to

come home

so I could sit

with him while he took his late supper, so that I could have a

chance to talk to him.

Q: What was he doing that he would be coming home so late?

A: He was a professor at Tehran University and later on became

the vice president of Tehran University and Dean of the Science

Department.

He

also helped found

Tehran University. He was a true teacher and very open minded.

The kids used to call him "Baba Agha" and he was father

to everybody and

helped

everyone he could. There are stories about how my dad helped people.

In 2000, I traveled to Shomal on a business trip, when a local

man was introduced

to me at lunch. Upon understanding who I was, he immediately

threw himself at

my feet and told me everything he had was from my father's help.

It turned out that he had once been a paparazzi, who it happened,

had

one day harassed

my father's guests. In response, my father had told him that

he should get a real job and went on to help him. The man ended

up

working

for him at the University of Keshavarsi, in Sari. Another time a burglar was caught in our old house; the house

where you had visited. The thief was trapped hiding under our dining

room table.

My father

ordered everyone out of the room and he stayed in there and talked

to the thief alone till 4am, even promising to help him get a job.

To my

father's

dying day, he blamed himself that he had not been able to help

this man.

My

father believed that education was the key to leading a decent

life and to being independent, for men and women. He never discriminated

between

men

and women; never favored his sons over his daughters. He gave

me a philosophy to

live by. What I am doing right now. Live each day as if it is

your last. Be good to people, be giving... life is all about giving...

it creates

a flow of energy... a cycle of life.

Q: I understand that philosophy; that one must give in order

to get. I try to live by that same philosophy. Your father sounds

like he

was a wonderful

person. I'm glad that I had the privilege to meet him. Let us continue:

When did you leave Iran?

A: I spent my childhood in Tehran. I had

very little knowledge of the rest of Iran.

I left for France when I was 18. Some of my character was formed

in Paris. I can say that is my favorite city.

Q: I noticed that you studied film making at "LIDHEC" (L'Institut

Des Hautes Etudes Cinematographiques.) When did you first develop

an interest in filmmaking and what was it like studying there?

A: I had a passion for film from a very early age, like many

others. Mom took us to the movies from the time I was three years

of age.

Hollywood films were

big in Iran in those days. So, I developed a taste for films and

later I studied film makers' life stories and... I remember,

the late

Hajir Dariush, - a film maker, a connoisseur of international films

and the

first

president of Tehran International Film Festival. He started a film

club at a young age, maybe 17. So, we mingled with them from an

early age.

In France,

I studied French literature and language at the Sorbonne.

During this period I studied the existentialists; Andre Gide,

Sartre, Camus; once my French became good enough. I improved my

French

reading on the

Metro. I had a very busy life going to school all day and going

out all night...

In those days, film school was not considered acceptable for

an Iranian woman in general. One day I ran into Parviz Kimiavi,

who

had studied

at "L'IDHEC."

He was the one who guided me on how to go about getting into the

school. I told

my dad about the film school. To my surprise, he asked me what

he could do to help! He also said that if he had his life to live

over

again,

he too,

would want to become a film director.

I had to take a four-month

course just to pass

the entrance exam along with 2,000 competitors. The "L'IDHEC"

prepares you for the exam with introductions to art, cinema and

culture;

mostly French, music history, art history, literature... I passed

the exam

and was accepted into the institute where I studied for two years.

There were two big filmmaker

professors I studied with there: Jean Mitry, a documentary maker

and George Sadoul, a film critic. It was a very hands-on school

and many

filmmakers such

as Costa Gavras come from that background.

Q: I want you to tell me about working with Albert Lamorisse.

In preparation for this interview, I did some research on him and

I am extremely impressed

with him. He made only 8 short films (average 38 minutes each)

in his life, which was cut short at age 48 by a helicopter crash

in

Tehran.

Of these

films, two were awarded Oscars.

The second was awarded posthumously

for the film

he made in Iran. He invented an apparatus enabling filming from

a helicopter called

Helivision and used it while making "Le Vent des Amoureux" over

Iran which cost him his life. Also I would add that there is

no one of my generation who has not seen: "The Red Balloon" when

they

were

a child

in

school

for which he won his first Oscar. He also invented and designed

many board games. A: Albert was one of the best documentarians at the international

level. Despite his great achievements, he was a very down to earth

person

and very spiritual.

I remember, he was terrified of Tehran traffic and he used to

hold on to anything or anyone for dear life, in the car at times.

He

was in a

circle

of French

mystics who lived in Iran at that time. His film:" Lovers Wind"

Bad Saba, is about mythology, messages from the mythological winds.

The

entire film was shot from helicopter.

I did my internship with him. He was making that film through

the Ministry of Art and Culture. I spoke French and was a film

student

and so they

sent me to be his assistant. I think unconsciously, his work had

a big influence

on me.

I must tell you the story about that helicopter crash. Albert

as I said was a mystic. He had always had a premonition that he

would

die

in Iran

over

water, in the Caspian Sea, but instead it was over the Karaj Dam.

The government insisted that he include footage of industrial

sites in order to show the West how much progress was being made,

even

though Albert did

not really want this part in his film. When we were scouting the

location at Karaj

Dam, he immediately expressed concern about all the high-tension

wires over the water and wondered how they would manage to fly

about without

running

into them.

I believe he had confidence in his pilot and his Helivision

system and

he knew more about the dangers than any body else in Iran. People

responsible at the office brushed aside his concerns, by assuring

him that he would

have the Shah's own personal pilot to fly the helicopter. The

day of the crash

I had called in sick. I learned about the shocking news a day

later. That was in 1970. His family was devastated. His wife went on

to finish the film from the notes he had left and submitted it

successfully

for

an Oscar.

Q: What an amazing but tragic story. Karaj Dam always

scared the hell out of me. I remember the first time I went up

there and

was

looking

down,

the wind

caught my hat and it was gone in a heartbeat. But what a privilege

it must have been for you to have known and worked with such a

great man.

It is

now my ambition to see and revive an interest in that film; it

sounds like it

must be absolutely gorgeous: an aerial tour of Iran... by browsing

the Internet, I have located only one copy which is residing

in UCLA's library. Next I want to hear about your experience

as one

of the judges at the Tehran International Film Festival. A: I had only been back in Iran a few years and I was working

for the Ministry of Art & Culture, later at NIRT and I taught at

the Film and TV Institute of Higher Education. The late Hajir Dariush,

a pioneer in Iranian Cinema, -

not well known to the public but known among film makers- became

the Director of the Tehran International Film Festival. I had worked

with Hajir and the

late great documentarian, Bahram Raipour before.

I can say these

two great filmmakers were my mentors. Hajir asked me to collaborate

on the film festival.

I remember the first film festival. We were doing all the tasks

ourselves, from serving on the selection committee, to the scheduling,

invitations, etc... Tehran

International Film Festival grew very rapidly and unexpectedly.

Suddenly everyone wanted to be in Tehran and every body was in

Tehran. From Maestro Fellini,

to Gina, Goldie Hawn, Lauren Bacal, you name it...

Q: I remember. I ran right into Michelangelo Antonioni

during one of those film festivals in the lobby of the Tehran

Hilton and

also

King

Emanuel

III, pretender to the thrown of Italy, who was living in exile

in Switzerland.

A: Being a judge was a good experience

for me. I learned about the politics, which went along with merit

as far as who received

awards.

Someone might

receive an award because he had been in the industry for 40 years

and had never been

recognized yet, even if there was a new guy who was just as good.

As a judge you make friends and enemies with your choices, and

a lot of

gossip

and animosity

are generated as well. But you have got to go with your heart and

do the right thing.

Q: When and why did you leave France for the USA?

A: I came to the USA in the late '70's. US culture had

become the focus of the world. I wanted to experience the life

style and

the new culture.

First I continued my higher education at USC and eventually, I

did work in my field, later, in the Hollywood studio system for

Columbia Pictures and Universal

Studios.

Q: How did you find the US compared to your experience in Europe?

A: I find Europeans more intellectual, more cultured,

better read and with a more relaxed life style. In the USA, the

government

and the

media are

run by the major corporations. It is all about corporations, not

people and for

sure not education, intellect or spirit, just material things,

sell, sell, sell, buy, buy, and buy. Bigger house, bigger car,

bigger...

One's

identity is based on material possession. Sometimes, I think these

people are really lost in transaction, rather than "Lost in Translation."

They

live to buy, kind of slaves to our material world.

Q: I know: consumer culture has replaced culture. American culture

is: buying things! I tend to agree with you after having grown

up for 16

years in Europe

myself. Sometimes I feel that our government, our institutions

and our producers, in trying to "serve the needs of everyone" end

up

serving the needs

of no one. It is all become so impersonal here and lonely. So what

made

you stay?

A: The Revolution made me stay. I had to start my life all over

and it took a long time. Survival became a real struggle.

Q: I know what you mean. I would have stayed on in Iran myself

if not for the Revolution. That life of 23 years ago seems almost

like

a dream

now

that never

really happened. One of my Persian friends told me she returned

home for the first time since the revolution this year and could

not get

over how

friendly

everyone was to her.

She went to a palace, now turned museum and

was dismayed to find the tour guide pointing out that one of

the private

offices there,

next to the Shah's office, had been her father's. She identified

herself to the guide and the tour group as his daughter and everyone

was very curious to ask her a lot of questions. Many young people

know very

little about

that time. A: The museum in Tehran was an out of body experience for us

too. One Friday morning, we were walking with one of my sisters

and

we were

passing by

the Niavaran Palace. We decided to go in. The experience was unbelievable.

The

same thing; the guide was talking about recent history as if it

happened on the distant horizon, centuries ago.

Q: Let's get back to cinema. Tell me about some of the other

Iranian film directors and actors that you have known. I believe

you are

a friend of Ghobadi? I found his "Marooned in Iraq" very moving

and powerful in its understatement.

I thought the way he had the

recurring sound of the American fighter

planes in

the background without any accompanying political diatribe, to

be very

effective.

I also thought

it was fantastic how the Kurds were in such close communication

amongst themselves, despite the rugged mountainous landscape

and national

borders separating

their many villages, that they could immediately spot an outsider. A: Ghobadi is very creative and talented. For the first time,

a Kurdish filmmaker is opening up a view to his culture, bringing

up the pain

and obstacles of

this region. His angles are very original. He is not duplicating

anyone else's efforts.

For the rest, I don't have a favorite though. I like many Iranian

filmmakers' work. My character is such that I only worship one

God, I don't create

lesser deities, just as with nature, I like all flowers not just

one over the others.

I have known Kiarostami for years. I find him extremely creative

and sensitive. He gives his audience room to think. I love his

visuals, very artistic

and poetic. He also tends to dwell on the morbid side of life and

brings

in the

harsh subjects of death and demolition, and yet, in such a delicate

way.

I love his "Under the Olive Tree", it is a masterpiece. And

then, there is Rakhshan Bani Etemad with her soft and Forough-

like style,

portraying the society she lives in, and Majidi, Panahi, and

obviously Makhmalbaf

and his family. I admire Samira's work and her character. She

has this super

star quality.

Talking about Iranian women rising to the international

level, Samira is one of the best known filmmakers. I was invited

to the

Montreal

International Film Festival, for "Mystic Iran." Samira was there,

chairing the

judges committee for young filmmakers. She was the center for

the international press and she has been for many years. Her younger

sister, Hana is

rising too.

Let's go back to the history of Iranian films. Many people who

are not in the business think that the rise of Iranian filmmakers

to

the international

level is a new phenomenon, but in reality, it goes back to the

'60's. There were directors like Mehrjui and Kimiaii, who are conventional

filmmakers with a line of social stories and the late Sohrab Shaheed

Saless, who was very

well known in Europe in his day.

Saless and I worked together at

the Ministry of Art and Culture. When he came back from Europe,

where he studied films,

he wanted to make a feature film, but the people at the center

wanted documentaries. He got funding for a documentary and came

back with a docu-drama film about

a switchman for the railroad focusing on the repetitive and boring

aspects of life.

Again, Parviz Kimiavi, he was a pioneer too. His first documentary

film "Ya Zamen Ahoo" is a breathtaking work of art. He went on

making films

with

no professional actors and using the beauty of Iranian landscapes.

"Bagh-e-Sangi" and "Mongols" are the same. The style of Kiarostami

and the new generation

Iranian filmmakers

has precedents. It has been carried and developed by them, but

not originated by him. Q: Speaking of current, tell us about our friend Shohreh Aghdashloo.

A: The first time I saw Shohreh, I think it was around 1974 or

1975, in Shiraz. I was invited to the Shiraz Art Festival.

Dear Farokh

Ghaffari, film maker,

critic and film historian, was the president of this Art Festival.

He advised

us to go see Shohreh's performance. Shohreh, had dyed her hair

blonde for the character. I remember when I saw her act; I

felt that she

would become one of Iran's leading actors.

I saw her 23 years later in Los Angeles. When I finished the

rough cut of my documentary film, I was looking for a narrator.

At first,

we were

looking

for

a male voice, but when we decided to go from 3rd person to

1st person story telling style, I decided on Shohreh! It

turned out

that she

had heard about

my movie and wanted to see it. She came to the studio to

watch the film. I remember she was in tears.

I asked her if she

missed

Iran

and she said:

"Yes,

but it is not just that." I worked with Shohreh on the

narration, many nights, late into the night. I knew she was auditioning

for the "House

of Sand and Fog" part. One day, on her way to the studio

to read the narration, she got a call that she got the part.

She

walked

into the

studio, happy and in tears. Janelle Balnicke, my co-writer

and Pam Parker Mosher,

owner of the studio where I was cutting the film and myself,

we shared this moment

of excitement with Shohreh.

Shohreh is very intelligent.

She

will not do something that would not come from her heart.

She preferred

not

to act

and refused many

parts, which were not her line of work. When she agrees

to the part, she is easy to work with, very giving and very

professional. She

read the lines

for

the film over and over again until she was happy herself,

even if I already was. She is an incredible actress with the

most beautiful voice.

Initially

I received some criticism from Iranians about Shohreh

narrating the

documentary, due to her accent, but that is what I

wanted. I

wanted an Iranian speaking

because it was supposed to be me speaking. As soon

as Shohreh's Oscar nomination was announced, all of the sudden,

all

the criticism stopped

and turned to support. It was only the Iranians who

had been critical, mostly

coming from lack of confidence and shyness about our

accent.

Other non Iranians loved

her voice and performance.

Q: It's funny; human nature. It's not just Iranians who

are hard on themselves and need to hear a foreigner

say an Iranian

is

good at something before they believe it themselves;

it is the same

for Americans.

Look how

many American singers, writers, poets and actors had

to gain recognition in Europe

first before they got any recognition back home in

the USA. All the writers of the '30's in Paris; even rock

stars like

Jimmy

Hendricks started in Germany.

Speaking of Shohreh, what did you think of her nomination,

her role, her film and her not getting the Oscar

award? I myself thought she

acted extremely

well

but I thought the film was too dark and not typical

of the Iranian

immigrant's experience in the USA, which has actually

been largely a striking success

story.

A: The fact that Shohreh was nominated for her very first American

film is a great thing. She just hadn't been in enough American

films yet,

but this will help her to go further in her professional life

here.

About the "House of Sand and Fog," I know people who loved it

and cried through it, and some didn't. It is a matter of personal

taste.

I think the film did bring some needed attention and dignity

to the plight of the Iranian Americans. Most of us lost everything

and struggled

mightily

and worked very hard when we came here and we were alone and

confronted

by prejudice and had to recreate ourselves all over again. For

the first time,

a major American film is talking about our immigrant society.

It is attracting a lot of attention and I hope it helps change

the

feeling of hostility

toward our community.

Q: Let's talk about your new film now! To begin, if you

don't mind, I should like to tell the readers of my impression

from the

private

screening that I had with just your DVD.

'Ary, it transfixed me!!! I sat spellbound without moving for

its entire 52 minutes. I believe that had I closed my eyes during

the Sama sessions that

I would have achieved an altered state.

Watching your film for

me was like

a religious experience. It was more than mesmerizing. You came

as close to portraying visually, an altered state of consciousness on film

as I have ever

seen. It is an impossible task to film an inner state of being

and the outer manifestation looks bizarre to the public and the eyes of most

Westerners and

yet even Christian fundamentalist evangelists have their rituals

and trance states and "speak in tongues;" as is mentioned in the Bible, so

it is not really as foreign as people would think.

The majority

of humanity passes through life in ignorance of the spirit dimension... most

modern individuals in post industrial societies around the world

hunger for spiritual truth and a purpose for life or put another

way, an experience

of

God... and our traditional churches have failed to provide this

and have become social clubs where the chance of gaining real

enlightenment is

exceedingly slim. They take our money or failing that, our services

in kind on committees

and prayer groups and such. We can pray but that is only filling

our minds up with our own words. It is by meditating and quieting

our minds

that we make

room for the outside to come in instead of always our endless

clutter of thoughts streaming out.

I remember that as a teenager I was

achieving

trance states

and I had no one to talk to in the society around me in Washington

D.C. about what I was going through. Small wonder that mystics

throughout the ages have

had to be secretive. Two centuries ago we burned our witches

in this country and now we would give them psychiatric evaluations.

I was

supposed to be applying

for college at the time and thinking about a major and all I

wanted

to

do was pursue mysticism but no Western university would offer

a degree in mysticism,

as they do now, so I had to settle for Anthropology which was

a distant second...

In my humble opinion science is not really

searching

for God at all but rather

seeking ways of allowing an individual to harness nature and exploit

energy and technology to increase the illusion of ego. In fact

modern science seeks

to cure death and the aging process as if it is a disease rather

than a doorway to eternity. The wonderful thing about mysticism

is that

it requires no proof;

one has only to experience it. We have lost touch with our inner

selves and this is the crisis of our modern times.

I recall the

words of Jesus: "Know

thyself... " if you want to know God. This is not the rule of hierarchical

priesthoods with seemingly endless lists of restrictions, like

the IRI, which is an extension of the rule of man. Sufis and mystics

have been martyred throughout

the ages because they are in touch with a part of human nature

that no Caesar can rule. No Caesar can rule our hearts. It is in ritual with its shocks that challenge or bypass the

usual conventions of our senses that an awareness or communication

with

this greater reality

begins. We ordinarily cling steadfastly to the perceptions of

our ordinary senses in order to give a manageable definition to

reality

but that

is not the whole picture. That reality is but a small part of

the "Unseen World"

of which your film is like a small window or a knock on that

door. In

ritual we

can suspend our self-censorship long enough to experience more

of what actually is the true nature of reality.

I mean, think of it this way; there was a time in Europe when

the church dictated that the earth was flat and the sun revolved

around

it. For

their discoveries

to the contrary, Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake and Galileo

was forced to recant. So even science has had its martyrs in

the past; sacrificed

by

the corrupt powers of theocratic governing authority, who felt

threatened for their

insisting on the truth. Look at the Spanish Inquisition... I also feel that today, this dark time we live in, is a storm

before the sun comes out and that we are on the dawn of a more

spiritual

time. I think

it

is what most people really want around the world in their hearts.

Everything in your film was relevant I thought. Even the street

scenes in Tehran, in the beginning, capture the on going struggle

between

"progress" and "tradition"

which is still unresolved after 23 years post revolution.

I was impressed by the filming of the Zoroastrian ceremonies

inside the sanctuary of Pyr Sabz and also how many women saints

are celebrated

in

Iran despite

the media created global impression that women in Iran are not

considered the equals

of men. I find Zarathustra's notion that evil is a creation of

the human mind while goodness comes from God and the human heart

particularly

powerful

and relevant today. It occurred to me after 9/11 that there were

a million ways that this government could have responded, rather

than

with bombs

and that a great opportunity to do good was lost.

You did a magnificent job of capturing on film the natural and

architectural splendor of Iran giving a context to the culture

of the dervishes

as well as the incredible landscape of mountains, deserts and

forests itself and

how it

helped to shape the people and the religions of this at once

ancient and modern land.

I think it is especially important in

these times

when the

IRI has made

the entire world think of Iran as reactionary as well as the

US media painting Iranians into terrorists, that outsiders are

made

aware

of

the profound

traditions of mysticism which still are alive and well albeit

secretive in Iran today

with cultural roots that are thousands of years old and always

with the same message that God is Love. This message is far

from the morality

police and

morality trials, stonings,"religiously" sanctioned rapes, tortures

and executions that have characterized the rule of the IRI.

Also the beauty and light inside the shrine of Hezrat-e-Massoumeh

(another female saint) and the rapture on the faces of the devoted

gave more

of a voice to humanity's religious expression than any words

could have...

25 years ago I went into a shrine in Shiraz and

kissed the tomb

of the saint there mimicking the pilgrims who were like the gentle

waves of an inland sea pushing against a far shore. Seeing a

similar scene

in your film

brought me right back to that long forgotten moment. Is it any

wonder that so many things of beauty especially in Iran have

the word" light"

in

them?" Garden of Light"," Sea of Light", "Mountain

of Light... " Even the word enlightenment has the word "light"

in it.

I loved the depth of your film, its simplicity, its respect for

history and past saints especially women, its respect for the

living and

its message of love. I think it is wonderful that the dervishes

allowed you to film

them

in

their rituals knowing that it would be viewed by the world. It

is almost

as if they too believed in the great importance of your mission

and wanted you

to take their message out to the world in your film as well,

at a time when we are in, what I feel, is a new Dark Ages; one

of

ignorance

of

the spiritual

reality.

Tell us about your own experience with mysticism and Sufism.

How old were you when you discovered this path and did you

have one

main teacher

or

guide? What

were you trying to accomplish with this film?

A: We are all born with these abilities. Sometimes the universe

forces us and opens the door for us to use the hidden power.

My experiences

didn't come until later and it was then that I went to see

masters at spiritual

centers and later on, at Sufi centers for guidance and to

understand what I was experiencing.

I have been on a spiritual path for a long time. I started

out practicing yoga and meditation when I was living in Paris

and

then I ended up

studying and

practicing Sufism later.

With mysticism you need a guide

at some point in

order to advance. It is hard to progress alone. I did not

have just one great master

but many masters in the U.S.A. and in Iran. I was told

that you don't have to look for the teacher; when the student

is ready,

the teacher

will come. The reason for my film and my going to Iran

in 2000 is that I want

to talk

about spirituality. I want to make a series of films on

spirituality in many parts of the world. This first one was about

Iran

because I know it

best;

I was born there and know the language and the country.

It seemed like the best

place to begin. The next film may or may not be made in

Iran. This Ritual, for me, is a combination of bodily exercise, meditation

and prayer; it is all encompassing. I had a car accident in L.A,

which left

me with back

problems. When I went through the women dervish ritual in Kurdistan,

my back pain left permanently. This ritual, sema and zekr, is

like yoga. It

is a

practice, which involves the physical, mental and spiritual.

I am a filmmaker by training and that is what I do. With this

film, I wanted to share my spiritual growth and pass it to others.

I

tried to

make it

easy to understand and easy to follow and I tried not to disturb

or exploit my

subjects either; it was a film from heart to heart.

Q: What

makes Sanadaj such a hub of Sufi activity?

A: Sanadaj is more open to outsiders perhaps because it is

so remote from the central government and large urban centers.

It

was impossible

to get

into the

Sufi centers in Kermanshah or Tehran where they are much

more secretive due to fear of government and non-believers.

Q: Once when I lived in Tehran back in the '70's as a teacher,

one of my students learned of the interest that my American

girlfriend at the time and I had in Sufism and he invited

us to a Sufi center

in Tajreesh of

all places right off the meydan which I had passed by many

times and never knew was there. The first thing I noticed

was that

an old, old man sat smiling

in the doorway handing out paper money to everyone who

came in. That was my clue that something was very different here

because

I have never been into

any other church or temple where I didn't end up having

to

part with money rather than be given any.

Then I noticed

that the

women though wearing

headscarves sat on the left side of the room in plain

view of the men on the right rather than behind them or in a

separate room.

Eventually after what

seemed like a long time, we got to the part of the ritual

in which, up in front of the audience, there was walking

on hot

embers with

bare feet like in some

of the sequences in your film. I remember when I came

back out

into the daylight, what a contrast it seemed like with

all the cars and buses and traffic noise

in such close proximity but a totally different mindset.

I wonder how you ever got the dervishes to consent to being

filmed? There must have been some very memorable experiences

that you

had while making

this film.

Can you tell us about some of them? Tell us about that

lady dervish whom I consider the star of your film. You

know the

one who was

baking bread.

She

was awesome.

A: Yes, you mean Aisha. We gave her the code name Aisha.

The most memorable experience I had was with Aisha.

In 2000, I had gone to Kurdistan and Sanandaj many times,

location scouting for the film. The first trip, I interviewed

only male

dervishes. They

were very kind. We smoked cigarettes together, which

made our Kurdish guide

very nervous. They promised to think it over about

being filmed, but no answer.

One day, our Kurdish guide asked me if I wanted to

meet women dervishes in Sanandaj. I ended up joining

in their

rituals.

I am not a spectator

but rather

a participant in life. After my participation with

them, the Khalife agreed to the filming at a later

date. Some

time later

the Khalife

invited me

and my crew to join her group of women dervishes

on a pilgrimage, which we did.

We started out at 3 AM following behind them in a

mini bus from Sanadaj to the village of Najar. We did not

arrive there

until

9 pm... it

was a very long and mountainous drive.

When we got

there, we saw a huge

Sufi center. I

went to the second floor, which was the women's

center. It was a dorm style room, covered with kelims on

the floor. The women

dervishes

started

the sema. I decided to take a picture, forgetting

that they

were taking their scarves

off. Most unfortunately my flash went off and all

the women dervishes started shouting: "film, film" and

covered over

their heads with

scarves. Khalife told me to sit quiet. I went to

the corner and kept quiet.

Everyone quietly went off to sleep. I realized

that I had disrupted the ceremony.

One of woman dervishes, Aisha, was still in trance

and she was "speaking in tongues." I was alone

with them

as everyone

else

was asleep. I

was worried about Aisha. She kept crying, lamenting

and growling.

Presently

as her friend came around, I asked her why Aisha

was in that state. I found out that her Sema

was interrupted

and

she

was stuck in

trance and

needed

to finish

the cycle of sema. I went down stairs and asked

Sheik Najar's daughter in law to join the circle and play

the Daf. Aisha

went through

the trance and dancing. Gradually one by one

the women dervishes sleeping

next door

awoke

and joined the circle of Sama. We finished around

4:30 in the morning. I

got close to Aisha and her friend after this

episode. The scene of fire eating happened the next day,

at 6am, while

she was

baking bread

for

the retreat. Q: What an incredible story.

A: Hostility and negativity can stop the flow of

positive energy and purification. The spirit

of the Sama can

be disrupted by

the thoughts

of non-believers.

I heard one story in Sanandaj among the men

dervishes that once when they were

performing the ritual and Tighzani (they cut

themselves or swallow razor blades, stones etc... ) unexpectedly

one of

them actually

bled. The sheik

walked right up to a non-believer in the audience

and asked him to leave. This is

why they normally don't allow outsiders. Nor

will

they perform for money.

Q: One of my friends told me that once, 40

years ago when she was in her late teens,

the prominent

Kurdish

family,

the Asef

Vaziris,

told

her that

Barnum

and Bailey Ringling Brothers Circus sent

agents to try to negotiate with some Kurdish chiefs

to hire

some of

the dervishes

for

their circus. They

were refused

and told that if dervishes performed for

money they would lose their power.

A: It is neither for fashion nor a magic

show. Some dervishes have gone to Europe

to perform,

but it

is a performance,

not the real

thing.

Q: I have heard that Konya in Turkey has

become pretty much a show for the tourists

by now

too. What a story!

Was there

anything

else

that happened

during the making of the film, which you

would like to share with us?

A: On our first trip into Kurdistan, we passed

by two young men, carrying huge boxes up

the mountainside, miles from

anywhere. I asked the driver

to stop

and give them a ride. After several hours

of driving they asked to be dropped right

in the

middle of

complete

wilderness.

I

was

puzzled

at

the time.

We stopped on the road a few times and

had lunch. Later,

we reached a plateau, on top

of the mountain and in the midst of it

there appeared this market out of nowhere.

There

were about 300

to 400 men,

and it was full

of huge

boxes.

It looked like

a swap meet to me. I decided to stop

and see what was happening. I noticed also

the two

young men

we had

given the ride,

earlier. Our

guide refused

to stop and kept driving, despite my

anger and frustration. Later I found out

that the market turned out to be a black

market, one of the spots where the

contraband goods, like cigarettes, alcohol,

electronics, weapons, and drugs exchanged

hands and entered

Iran, via Iraqi borders.

We were

told that

we could easily be kidnapped and disappear

in the mountains.

Q: Well I think you could write a whole

book about your experiences making this

film in

Kurdistan. I am sure

that it will be

a great triumph for

you regardless of whether you end up

selling it

to National Geographic or PBS

or how it eventually

will come to market. I wish you all the

success with this film that it so richly

deserves

and I am sure

that our

readers can

hardly wait

to

see it.

Let's

talk a little bit more about the cinema

industry in general and how you would

characterize the differences between

Iranian, European

and U.S.

cinema.

A: I think that creation and art

are the reflection of the people and the

society

they live in,

the soul of

their culture.

In the

US, it

is more

about action

and violence. If we go back to the

early films, such as Wild West and cowboys,

to the nowadays-virtual

reality films,

there has been

no change

in the

script. It is still the good guys against

the bad guys, from chase scenes on

horse back, to fast cars, to airplanes, to

cruise missiles and

now virtual entities, it remains the

same scripts... Even the spiritual

films

are about bad spirits.

Q: You are right. Even in a comedy

such as:" Ghost Busters "the spirits

are portrayed

as evil and

demons to be fought.

I personally

think that it is all a part of the

conspiracy on the part of the capitalists

to keep

the

masses stuck on consumption. The

spiritual world is one area of existence, which

they would not

be able

to merchandise

so they

use the media

to make it a fearsome place to be

fought and avoided because they can't

sell it

in the market place.

Like I said

the culture of America is:

buying stuff.

Dying is un-American and yet they

have even made a big industry out of the

funeral business... money, money,

money... Every

religious holiday; Christmas, Easter,

even Valentine's

Day has been commercialized

and turned

into opportunities to sell something

and go to bazaar. I think violence and sex in the media

is a way of keeping consumers minds

distracted from

ever

thinking

about

the deeper values

in life and who

is really in control

and in charge of their lives. Consumption"

is the opiate of the people" or

as Julius Caesar once

said:" Give

them bread

and circuses...

."

In this way we remain indebted

wage slaves for

the capitalist oligarchy. Our cars

and our TVs even act

to cut us off

further from each other

so

we don't

get to share our grievances and

foment revolutions.

We live in cocoons afraid

of our neighbors,

afraid to let

our kids

play

in our front

yards, let alone

bike the neighborhood. We don't

talk to

each other here. I have never

lived in a society

where so

many people

are living

lives

of quiet

desperation in isolation. Small

wonder people go postal. Why for example

would they make a film about

a woman serial

murderer and award her an Oscar?

It is sick when

you think about it, but as you

said our art

describes our culture.

A: There is definitely a love affair

with violence in American culture,

which perhaps

psychologists

could investigate...

. but there is more

to the human experience than

fighting and destruction. Once

in a while, Hollywood makes a

good film

and some

are extremely creative

and unique,

but not

enough.

We live

in the capital

of the movie industry, but it

seems like a facade. That's all.

But

the fact is

that European

and

Iranian films

are very different.

There

films

have a human message, both emotional

and intellectual versus commercial.

I mean

look at the history of American

film. Where did it begin?

Q: Griffith, "The Birth of a

Nation?"

A: Yes, this was about war.

If you look at the history

of American

film

it is

so devoid

of emotions

that

the moment an actor shows

emotion or

cries, they are up for Oscar.

The mainstream culture does

not value

human characteristics,

but it is based on materialism,

as we spoke.

Q: I know. Here the attributes

of machines are admired

over the foibles

of humans.

They once

took their

greatest poet

Ezra Pound

and locked

him up.

I remember when I first

came back to America at age 16

after growing

up

in Italy,

I found that the only guys

I could make friends with

here who had

any interest

in the arts,

culture or

intellectual matters

were

either Jewish

or gay.

A: People have lost touch

with reality and I feel

TV and cinema

are largely

to blame.

I know

an American

couple that thought

the bombing

of Iraq

was "awesome!"

Q: I am reminded of how

difficult it was for

me to fathom the

reality of

the jet

liners hitting the

World Trade

Centers on

911 because

it looked so much

like just another disaster

movie like "Towering

Inferno" or "Titanic."

A: The US cinema is

superficial. Going

into depth here

means transferring

an idea to

something that sells.

People have

no time to think

here. European movies

have more sensitivity

and leave more room

to think.

In the

IRI there is

pressure from the

government

and the

threat of censorship,

so

the stories

became symbolic.

You have to look

for the hidden message.

You have

to look with

the eyes of

the

spirit.

Q: In my interview

with our mutual

friend, film

maker

Parvin Ansary,

we talked about

how great

artistic

creations come

out of great

suffering and

adversity

while affluent

societies become decadent and

produce decadence.

In Italy,

the great film

era was after

the war, which

was a time of

much suffering,

poverty

and self-loathing

for their role

in Fascism.

By the

time they

had recovered

and become

an affluent

society

their

era of great

cinema

was over...

A: Well in a way,

you could say that

Iranian

films

come out of

a culmination

of great

suffering; regardless

of

whether

we live

inside

or outside

the country. Both

sides have suffered.

Q: You know I am

reminded of something

that the

Dalai Lama

alluded to

which was that

when the

Red Chinese

conquered his

country and forced so many

Tibetans into

exile, the refuges took

the wisdom

of Tibetan

Buddhism out

into the

world with them

for the benefit

of the

rest of

humanity rather

than

keeping it confined

to the remote

fastnesses of Tibet. I

hadn't thought

about this until

now but

the Iranian

Diaspora

similarly has

brought

Sufism

with it

out into the

world from its seclusion

inside

Iran and

this

is a great

opportunity for

the rest of humanity.

A: They say "Gol Niloofar grows out of ab lajan." (The water lily

grows out of stagnant water.) Q: Now, I want to thank you for the privilege you gave

me of seeing your film and the time you have sacrificed from

your busy

schedule to make this interview.

Thanks again!!! It's been incredible and I'm sure the readers

will agree that it has been a real education. I will miss our weekly phone

conversations.

A: Sorry for the delays and for making you chase me from city

to city, and country to country on the phone, to finish this interview,

but this is the

American life style! .................... Spam?! Khalaas! *

*

|