|

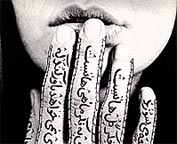

By Cyrus Samii REVIEW: Shirin Neshat's short videos, "Possessed," "Passage," and "Pulse" run on continuous loops at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery, 515 W 24th St, New York, New York, until June 29, 2001. Shirin Neshat is a darling in the art world right now, esteemed for "conveying the universal" in her eloquent portrayal of "Islamic culture". But none of that talk should distract expatriate Iranians from indulgently claiming for themselves these moving meditations on identity. Her symbol-juggling stirs up all of my ambivalent feelings about being Iranian-American. Cross my ambivalence with her ambiguity and the outcome is a tangle; but this exercise in matching uncertainties happens under the discernible theme of Iranianness. Employing provocative counterpoint in her photos -- guns and femininity, lipstick and chadors -- Neshat's poster-like images stir up the grand questions that haunt Iranians who are caught between cultures: Revolution inspires but what has it brought? When removed from the immediacy of struggle, does choosing sides help anything? At what point is one being dishonest in their connecting to a culture? What responsibility does one owe to a heritage? Neshat's graceful depictions convey a strong message: There is no resolution to these questions, but within the ambivalence, there is much to cherish and celebrate. Neshat's video pieces, which constitute much of her output in recent years, waver between consciously conceived melodrama and brooding. Mostly shot in black and white and often accompanied by reverberating sound collages, the videos invite the viewer for quiet contemplation deep within the heart of the Iranian identity crisis. Last Thursday I took up Neshat's latest offerings -- three video pieces on display at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York City. Following are accounts of my indulgent claiming of Neshat's meditations on identity. "Possessed" A beautiful but nervously trembling woman floats and sings through craggy-walled alleys that typify pre-modern urban Iran, even though this film was shot in Morocco. It's easy to imagine the girl from Panahi's "White Balloon" running through the scene with her goldfish. The protagonist's wild curly hair is left uncovered, a clear provocation. I am immediately reminded of my sister's hair on humid summer days. My sister and I grew up in Pennsylvania's summer humidity. My father told my sister and I that the Pennsylvania humidity was nothing compared to summers in Rasht, where he grew up, and where uncovered curly hair would spring out in devilish frays. After slipping through an unnoticing crowd, the singing woman with wild hair climbs onto a stage in the middle of the small town square and maniacally wails. The thick, echoing soundtrack slides in and out of sync with the woman's wailing. The crowd's uproar was foretold by that wild hair. I cannot help but fixate on a very dark-skinned man in the scene. As with many of the other actors in the scene, his pretend hostility is transparent. If my grandmother were watching, she would certainly notice him, the "siaah." If my mother and grandmother were here watching this together, they would comment on him to each other. Somehow, the wild-haired woman slips off the stage, leaving the crowd bickering among themselves. The film has efficiently constructed an allegory for controversy and infighting. One reviewer has declared it an allegory for an artist's life. But this strays too far from the tension between hejabism in Iran and the fantasies of freely exposed wild hair. "Passage" Phillip Glass's score for "Passage" is absurdly grandiose. It demands that the scenes and characters be read archetypally: corpse-carrying men marching on the misty beach, the chador-draped diggers in the desert, and the unexplained little girl piling stones. Neshat's intimacy is smothered under awkward abstraction. The girl's hands seem too brown; why is she covered in dirt? The women's faces are too austere. These are not Iranians like the ones I know. This is the desert toil of a nineteenth century painting. These chadors and beards embarrass me. At the end of the film, a flame rips across the desert and encircles the men and women in an enormous ring of fire. But there's nothing to this; the music fails; all I can think of are the film crew's delighted claps, gasps, and shouts. "Pulse" I am sitting Indian style on the floor of the dark gallery room watching "Pulse." The sultry woman on the screen sings along to the radio in the dark. I have sat before like this, Indian style and in the dark, watching music videos. I watched my first music videos when I was twelve in my aunt's living room (Ameh . . .). The hypersexual woman singing and dancing on television was arousing me. I had the television's volume almost all the way down. I hoped my Ameh would not wake up and come out to force me to face my guilt. My memory of arousal is matched by what is happening in Neshat's video: the woman on screen sings along to a duet. She is intoxicated by the singing man as he voices the time-defying lyrics of Rumi.

|

|

|

Web design by BTC Consultants

Internet server Global Publishing Group

Moving meditations

Moving meditations