Shakespeare in the Islamic Republic and Sa’edi in Ohio Shakespeare in the Islamic Republic and Sa’edi in Ohio

Performing Ghlamhossein Sa'edi's "Othello in Wonderland" in Ohio

Ali Akbar Mahdi and Elane Denny-Todd

November 23, 2005

iranian.com

Twenty years ago on this day (23 November 1985), Iranians lost one of their brightest and most productive fiction writers and playwrights of the 20th century, Gholamhossein Sa'edi (1935-1985). In his last year of living in Iran, Sa’edi crafted the outline of a play he could not write in Iran. After fleeing into exile, he developed the idea into a play later called Othello in Wonderland.

As political art, the play was very much a reflection of its time, and showed what was happening in Iran in theearly 1980s. The play was immediately adopted and directed by Naser Rahmaninejad in spring of 1985, before it even saw the ink of print. Sa’edi was present for this performance, and was reportedly extremely pleased to see it on the stage with such a strong cast of Iranian actors.

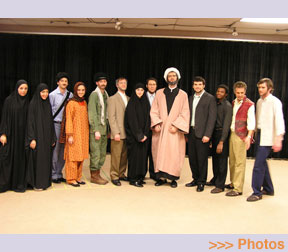

Now, twenty years later, this play has been staged by an American cast, in the English language. The play was offered at Ohio Wesleyan University as a component of the 2005 Sagan National Colloquium on “The United States and the Islamic World: Challenges and Prospects.” There were five showings of the play, and it received widely positive reactions from audiences. What follows is a report and reflectionon this play, and on how the student cast adjusted to a foreign play by reflecting on cultural nuances rarely perceptible to Americans >>> Photos

Othello in Wonderland: Summary and Reflection

The plot of the play is fairly simple: a group of thespians are rehearsing Shakespeare’s Othello,which is soon to be staged in Tehran. The director has gone to the authorities to get permission to put on the play. He receives permission under the stipulations that it must not use any lurid phrases, must conform to Islamic values, and must serve the objectives of an Islamic government.

As the director tries to convince his actors that they can conform to the authorities’ demands by means of only minimaladjustments, the Minister of Guidance and his entourage -- a male and a female guard, a professor, and a director -- arrive,and they begin to criticize every word, line, and act of the play.

Their suggested modifications regarding the use of language, dress, and Shakespeare’s conceptions of human relations lead to a series of absurd, ironic, and hilarious moments in the play. The cast is asked to dress according to Islamic codes, marry each other if male and female are not related, and submit to enema tests. The actors become frustrated and resentful, and some express the desire to quit the play.

The portentous, pompous authorities demand that they remain in the drama, because artistic production is very important to the advancement of the Islamic revolutionary cause, and thus the actors are religiously obligated to continue with the show. In light of the actors' resentment and unwillingness to conform, the officials allege that the play is a Zionist plot, connected to Monafeqin, and thus proclaim that it has to be monitored very closely.

While in Iran, Sa’edi was an astute critical observer of the cultural scene. The political repression that swept the country following the clerics' seizure of power in the 1979 revolution forced Sa’edi to exile. In exile, Sa’edi remained as productive and sharp a critic as he had been in Iran. To expose the tragic consequences of the Islamization of art, Sa’edi wrote Othello in Wonderland – a tragic-comic work reflecting on the calamity and absurdity of trying to Islamicize Shakespeare’s Othello.

From the moment of its inception, the Islamic Republic showed a direct hostility to freedom of expression outside of its own Islamically defined zones. Art, which is based on creativity and imagination, was a frequent target of Islamic ideologues who were so convinced of their own beliefs that could barely tolerate “non-Islamic” views and expressions, especially if they originated from the West. In other words, whatever is not “Islamic,” in the fundamentalists' perverse view, has to be clumsily distorted or excised --in a word, censored.

This play shows how, in an ideological society, fear is instilled in artistic words, gestures, and movements. Artists have to be fearful of what they say, do, and even think. Crude, ham-fisted norms are enforced by judges who know absolutely nothing about acting or theater. Yet these self-appointed guardians of thought see art as a necessary tool for distorting reality into their own preconceived notions of truth.

A direct attack on the negative consequences of religious censorship, Othello in Wonderland is a strong piece of political satire. The farcical nature of this play and the depiction of the absurdity of words and relationships that are produced as a result of religious censorship are so risible that they keep viewers laughing throughout the play. A direct attack on the negative consequences of religious censorship, Othello in Wonderland is a strong piece of political satire. The farcical nature of this play and the depiction of the absurdity of words and relationships that are produced as a result of religious censorship are so risible that they keep viewers laughing throughout the play.

But the laughter is mixed with pain and tears. In this play, laughter is not a response to the comic foibles of human nature, but a painful reaction to the absurd situations that the actors find themselves in, as they are forced to obey the ideological commands of the religious watchdogs.

Sa’edi’s humor not only mocks the clerical authorities overseeing the adaptation of this Shakespearian play, but demonstrates the shallowness of their minds, the ludicrousness of their views, and the excessiveness of their demands. Their demands betray the actors more tragically than Iago undermines Othello in Shakespeare’s play. They turn the script into a grim piece of absurdism that implicitly protests both artistic censorship and religious dogmatism.

Twenty-six years have passed since Iranians confronted the realities of Islamization in their society. In the early days of the revolution, many chose to remain optimistic and less critical of revolutionary demands upon Iranian art and literature. Sa’edi was one of the few who did not share this optimism. His imprisonment, his year of torturous life in hiding, his subsequent experience of fleeing his homeland, and his foresight convinced him that difficult days would be ahead for his colleagues and his homeland. In its prescient way, Othello in Wonderland demonstrated how art can become a fraud, and warned us about all that would come afterward!

American Cast & Audience Reaction

Othello in Wonderland. An Ohio premiere, produced at Ohio Wesleyan University by the Department of Theatre & Dance.*

To provide an artistic dimension to the Sagan National Colloquium, efforts were made to select a play that reflected issues and concerns in Muslim society that also related to the United States and the World. Director Elane Denny-Todd reviewed a series of plays, and Othello in Wonderland was ultimately chosen because of the play's combination of humor and bold message. At the heart of Sa’edi’s play are the issues of free speech and artistic, political, and individual freedom. His message speaks as loudly today as it did when the play was written. The play is universal; it resonates throughout the world, in any place where censorship of any form exists.

The characters are multi-dimensional, reflecting both the authoritarians and their followers, and regular, everyday, working people. The play speaks loudly about censorship – a topic that American actors and audience could relate to comfortably. This worldwide issue was explored and through this play, the significance of the kinds of censorship specific to Iran was better understood.

The actors and director went about their usual task of analyzing and understanding the script, and were also immersed into what was, for most, a totally new cultural experience. This was discovered most specifically in the use of the veiling for women, and the extremes of the Zeynab Sister. For the American student actors, moreover, the parts of the two professors were challenging. The mannerisms and gestures (e.g., stroking the beard, using prayer beads) contrasted with much of what the actors had previously observed in their American professors. The actors and director went about their usual task of analyzing and understanding the script, and were also immersed into what was, for most, a totally new cultural experience. This was discovered most specifically in the use of the veiling for women, and the extremes of the Zeynab Sister. For the American student actors, moreover, the parts of the two professors were challenging. The mannerisms and gestures (e.g., stroking the beard, using prayer beads) contrasted with much of what the actors had previously observed in their American professors.

The American audience and actors could recognize the clerical characters from the images presented in the mass media, but the language patterns, rhythms, gestures, and non-sensical comments initially took some time for the American audience to comprehend. Could someone in authority not know what he is talking about? Yes! was the resounding answer that Sa’edi put so clearly into his script.

At the same time, of course, the American actors could associate easily with the “actors” within the play, and were able to play double roles because of the “play within the play” concept. Sa’edi’s dialogue revealed that just as in any troupe of actors, the role played on stage is not who the actors are in everyday life. This was a point of humor for the audience, as the dim-witted Revolutionary Guard could not understand this concept.

Since the play was to be part of a colloquium on the relationship between the United States and the Islamic world at an American university with a small community of students and scholars, it was apparent that the majority of people to see or be involved with the production would not be Iranian. Therefore, it was important that the play chosen be written and performed in a way that was true to the Iranian people and culture. This can often be a fine line in comedy. Thus, every attempt was made to produce a performance consistent with the ideals of the playwright.

Particular attention was put into coaching the American actors on details of physicality and expression. The American cast and director knew that some of the play's substance would be “lost in translation" to a non-Iranian audience, but nonetheless felt that the work stood on its own. Because the American actors, and most of the American audience, were already familiar with Shakespeare's original Othello, the director chose to stay as close as possible to the American interpretation of the lines taken from Shakespeare. Furthermore, the American actors did not attempt an Iranian accents or dialects, out of respect for the culture and language. Particular attention was put into coaching the American actors on details of physicality and expression. The American cast and director knew that some of the play's substance would be “lost in translation" to a non-Iranian audience, but nonetheless felt that the work stood on its own. Because the American actors, and most of the American audience, were already familiar with Shakespeare's original Othello, the director chose to stay as close as possible to the American interpretation of the lines taken from Shakespeare. Furthermore, the American actors did not attempt an Iranian accents or dialects, out of respect for the culture and language.

Overall, the Ohio premiere of Sa’edi’s play was a resounding success and well-received by students and audiences >>> Photos

* This production was based on the English translation of the play by Michael Philips. We appreciate cooperation of Mazda Publisher and Dr. Mohammad Ghanoonparvar.

About

Ali Akbar Mahdi is Professor of Sociology at Ohio Wesleyan University and author of award-winning book, Teen Life in the Middle East. Elane Denny-Todd is Professor of Theater at Ohio Wesleyan University and has worked professionally as an actress/director in over 100 productions in Equity, regional, and academic theatres.

|