Cover story

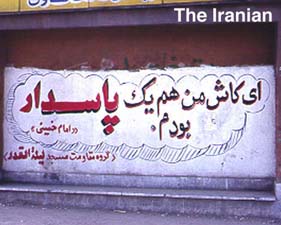

Photo by J. Javid. For more related photos, click

here

From Khomein

A biography of the Ayatollah

June 14, 1999

June 14, 1999

The Iranian

I.B. Tauris has published a second major biography of an Iranian

leader in less than a year. Last fall, we ran an excerpt from the first:

Cyrus Ghani's Iran

and the Rise of Reza Shah.

The following are excerpts from Baqer Moin's Khomeini:

Life of an Ayatollah. Moin is a specialist on Iran and Islam and

is Head of the BBC's Persian Service.

Also see related

photos by Jahanshah Javid.

* Family

* Father

* Childhood

Family

Ruhollah Khomeini was born on 24 September 1902 in a house that stood

in a large garden on the eastern edge of the village [of Khomein, deep

in the vast semi-arid areas of central Iran, some 200 kilometers northwest

of Isfahan]. A spacious two-storied structure built around three courtyards

in a style common to the homes of the prosperous throughout provincial

Iran, it had cool balconies and two tall watchtowers - one overlooking

the river to the fields beyond and the other the surrounding streets and

gardens...

Khomeini's family are Musavi seyyeds; that is they claim descent from

the Prophet through his daughter's line and the line of the seventh Imam

of the Shi'a, Musa al-Kazem. They are believed to have come originally

from Neishabur, a town near Mashhad in northeastern Iran.

In the early eighteenth century the family migrated to India where they

settled in the small town of Kintur near Lucknow in the Kingdom of Oudh

whose rulers were Twelver Shi'a - the branch of Islam which became the

official state religion in Iran under the Safavids and to which the majority

of Iranians adhere today.

Ruhollah's grandfather, Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi, was born in Kintur

and was a contemporary and relative of the famous scholar Mir Hamed Hossein

Neishaburi whose voluminous history of the religion, the Abaqat al-Anwar,

is sometimes described as the pride of Indian Shi'ism.

Seyyed Ahmad left India in about 1830 to make a pilgrimage to the shrine

city of Najaf in present-day Iraq, and possibly to study at one of its

famous seminaries. He never returned. In Najaf he struck up a friendship

with Yusuf Khan Kamareh'i, a landowner who lived in the village of Farahan

not far from Khomein who persuaded Ahmad to return to Iran with him.

It is thought that the two men made the journey around 1834. Five years

or so later, in 1839, Ahmad purchased the large house and garden in Khomein

which was to remain in his family for well over a century and a half. Whether

he had brought money with him from India or made it in Iran, he was clearly

at this time a man of substance as the 4,000-square-meter property cost

him the very large sum of 100 tomans.

He had already married two wives from the district, Shirin Khanum and

Bibi Khanum, and in 1841 he took a third, his friend Yusef Khan's sister

Sakineh. Ahmad had only one child from his first two marriages, but Sakineh

gave him three daughters and a son Mostafa, who was born in 1856.

The family continued to prosper as , over the next decade, Ahmad bought

land in the small villages of the region, and in Khomein itself an orchard

and a caravanserai. He died in 1869 and, as he had instructed in his will,

the family took his body by mule to the holy city of Karbala for burial.

To top

Father

Still a young boy at the time of his father's death, Khomeini's father

Mostafa, as was customary in those days, trained for the family's religious

profession. He studied first in a seminary in nearby Isfahan and then in

Najaf and Samarra...

Mostafa seems to have ... lived the life of a landed provincial notable

whose clerical background, wide-ranging connections in the region, and

strong personality enabled him to become something of a community leader.

Inevitably, hagiographical accounts of Mostafa's character have, given

the almost god-like status achieved by his youngest son and the lack of

contemporary records, proliferated since the 1979 Iranian Revolution. These

tend to portray him as a man who came to be a popular and influential figure

because he was "close to the ordinary people" and, unlike many

clerics and chiefs "stood by the small farmers and peasants in their

problems with the landlords and government officials."

There may well be an element of truth in such claims. But the noble

qualities they attribute to a man of this period were of a different kind

than those implied by the vocabulary of modern populist politics. The role

of a man like Mostafa played in his community should be seen against the

background of the lawlessness and insecurity that prevailed in many areas

of provincial Iranian his day and the idealized function, in such circumstances,

of the good "notable"...

But such a position carried its own dangers. On a cold day in March

1903, less than six months after the birth of his third son Ruhollah, Mostafa

was shot and mortally wounded on the road from Khomein to Arak. He was

only forty-seven-years old.

A number of imaginative stories have circulated since the 1979 revolution

about this incident... An account that is undoubtedly closer to the truth...

is that given by Morteza, who was only eight-years old at the time of his

father's death, but, as his eldest male heir, was deeply involved in the

events that followed it. It is worth paraphrasing ... for the vivid picture

it provides of the society into which Khomeini was born.

In the second and third years of the twentieth century, life for the

people of Khomein was, Morteza relates, made particularly miserable by

three local khans - Bahran, Mirza Qoli Soltan and Ja'far Qoli - whose predatory

ways oppressed the population. The worst of them was Bahram Khan, who was

arrested and jailed by Heshmat al-Dowleh, a powerful Qajar prince who owned

huge tracts of land in the region.

Bahram Khan was later killed or died in prison, but his two companions

continued to harass the people. As the situation got worse, Mostafa decided

that something must be done and that he would go to Arak to ask the provincial

governor, the Shah's son Azod al-Saltaneh, for help...

He left for Arak, which was about two-day's journey from Khomein, with

ten to fifteen horsemen and armed guards. The next day, as he was riding

ahead of the party flanked by only two of his guards, Ja'far Khan and Mirza

Qoli Soltan appeared on the roadside. They were unarmed.

"You were supposed to stay in Khomein," Mostafa said. "Well

we didn't obey you," they replied. "They offered our father sweets

and then suddenly seized a rifle [from one of the guards] and ... aimed

at his heart. The bullet went clean through the Qo'ran my father had put

in his shirt pocket and pierced his heart. He fell from his horse and died

instantly." ...

To top

Childhood

[After his father's murder] the young Ruhollah was brought up [in a

bleak, somewhat hair-raising environment following the Constitutional Revolution

of 1905] by his mother [Hajieh Agha Khanum], his wet nurse Naneh Khavar

and his Aunt Sahebeh, who had no children of her own and had moved back

into the family home to help with her brother's orphaned brood...

Sahebeh seems to have been a major influence on the family and legends

of her strength and courage abound. Ahmad, Khomeini's son, says that in

the absence of a shari'a judge in Khomein, Sahebeh had once carried

out his duties for a few days until a replacement could be appointed. If

this story is true it is most unusual since in Islam women are not allowed

to become judges.

Ahmad also relates that: "Two rival groups of the people of Khomein

were involved in a shooting incident. Sahebeh interfered and placed herself

between the feuding factions, ordering them to stop shooting. Her power

and charisma were such that they immediately obeyed her."

Whether as a result of his genes, or of influences such as Sahebeh,

Ruhollah was clearly a spirited child. The family recalls that he was very

energetic, playing all day in the streets and coming home in the evening

with his clothes dirty and torn, often bearing the wounds of scraps with

his friends.

He was also physically strong and his abilities meant that as a he grew

older he became something of a champion at sports. He could beat other

children in wrestling, but his favorite game was leapfrog and in this he

was considered the local champion...

Ruhollah remained in the maktab until he was about seven and

then attended a school built in Khomein by the constitutional government

as a part of its effort to modernize Iran's educational system. In addition

to Persian language and literature, at this school he would have had an

elementary training in subjects such as arithmetic, history, geography

and some very basic sciences. He also had private tutors ...

When he was fifteen he started learning Arabic grammar in a serious

fashion with [his older brother] Morteza, who had studied Arabic and theology

in Isfahan. Morteza, who had a good hand, also worked with his younger

brother on his calligraphy...

Khomeini's childhood drew to a close towards the end of the First World

War when his mother and aunt both died in a terrible cholera epidemic that

raged through Iran in 1918. He was sixteen and about to enter the seminary

[in Qom]...

Khomeini ... left his birthplace and a turbulent childhood behind him.

He was, by all accounts, a determined, assertive and serious young man.

But beyond that, little is known about him. Had the murder of his father

created in him a spirit of revenge, not against the murderers or their

families, but against the supposed instigators of the murder, the authorities?

We do not know...

The picture painted for him of his father as a man who campaigned for

"truth" and opposed "falsehood", unbelievers and oppressors,

may well have deeply affected his impressionable mind and provided a model

of conduct for him to look up to.

- Send a comment for The Iranian letters

section

- Send a comment to the author,

Baqer Moin

![]()