Off the grid Off the grid

Reading Iranian memoirs in our time

of total war

Negar Mottahedeh

September 21, 2004

iranian.com

Air-conditioned transportation in Tehran is notoriously

difficult to find. For pampered visitors such as the cultural anthropologists

and documentary filmmakers from New York and Los Angeles who seem

to converge on the Iranian capital every summer, a cool taxi ride

to the northern parts of town recalls something of the charmed

life they left behind in the United States, a life some refer to

offhandedly as "the grid."

Being on the grid, it seems, is something akin to having a non-Iranian

passport or a green card, multiple credit cards loaded with debt,

a laptop with a 24-hour DSL connection, satellite television in

an air-filtered apartment, impeccably pedicured feet in open-toe

sandals, a single Gauloise cigarette ashing in a saucer next to

that daily injection of coffee and money earned from a steady job.

This is not to say that some of these components of the grid are

not available in Tehran. They are.

Apartment complexes in the northern

parts of town, like Shahrak-e Qarb, also provide residents with

hilly, green outdoor spaces where a woman can walk her dog without

the government-prescribed full body covering and headscarf. Such

private complexes come with in-house supermarkets, boxed meals

delivered to your door and a doorman who will call a taxi and

announce visitors just as he might at a one-bedroom pad in New

York. In

Tehran, all this comes to about $500 a month.

In our time of total war, however, Tehran visitors' moniker for

the good life also evokes the frightening world of intelligence

gathering networks and terrorists recently fictionalized in the

TNT miniseries The Grid. In this terrifying world, some of those

visitors, wittingly or no, have acted to embed the particulars

of Iranian cultural and social life -- particularly those related

to Iranian women -- into visions for Iran's future that are generated

in a grid entirely different from their matrix of material comforts.

It cannot be coincidental that the memoirs by Iranian female

authors now living in the West, such as those of Firoozeh Dumas,

Marjaneh

Satrapi and Azar Nafisi, have found such phenomenal commercial

success at a time when Washington hawks would like these authors'

country of birth to be the next battleground in the total war

of the twenty-first century.

FREEDOM AT WHAT COST

It is entry into the grid -- in both of the above senses of the

term -- that best describes Firoozeh Dumas's memoir, Funny

in Farsi: A Memoir of Growing Up Iranian in America. Upon her family's arrival

in America in 1972, the young Firoozeh and her mother discover

that Firoozeh's father, an engineer who had studied in the US some

years earlier, has no useful knowledge of the English language

except for the vocabulary he had needed to read pre-World War II

textbooks. Her mother eventually teaches herself how to ask about

the prices of everyday necessities and kitchen appliances by watching

The Price Is Right on television.

Fifteen times, Dumas counts, the family visits Disneyland, but

as is typical of Iranian cultural patterns, these outings were

enjoyed in a tribal fashion. On several occasions, her father brings

along his Iranian colleagues and their families, sometimes six

families in all. The grid is, within months of her family's arrival,

being adapted to old habits of a life lived elsewhere. The family

celebrates Thanksgiving with turkey and stuffing, but the pumpkin

pie is served with Persian ice cream made with "chunks of

cream, pistachios and aromatic cardamom."

Dumas's recollections

of Thanksgiving dessert prompt this insight into world politics: "I

believe peace in the Middle East could be achieved if the various

leaders held their discussions in front of a giant bowl of Persian

ice cream, each leader with his own silver spoon. Political differences

would melt with every mouthful." (75) Sensuality and utopian

hope do not alleviate the sophomoric imagery in this vision of

change: what fools, what diplomatic failures, the reader must imagine

the political leaders of this region to be!

Dumas's family gives thanks around the holiday dinner table for

their new life in a free country where one can pursue one's hopes

and dreams -- even if one is female. But while, for Dumas, freedom

certainly entails such essential rights as the right to vote, it "also

refers to the abundance of samples available throughout this great

land."

True to her naive view of Middle East diplomacy,

she contrasts this abundance with the environment she left behind

in Iran. "Here, a person can taste something, not buy, and

still have the clerk wish him a nice day." (75) Few living

in the Islamic Republic today would see the widespread practice

of communal hospitality known as nazri as somehow less free than

Dumas's sampling. For Dumas, it would seem, freedom in America

is the endless possibility of self-indulgence understood without

any self-reflection. This is freedom, yes, but at what cost?

Total war? Occupation? Perhaps.

"TODAY IRAQ"

Driving north on the Sadr freeway in Tehran in the summer of

2004, I came across a series of images covering the soundproofed

walls of the opposite lane. The first panel from the left was a

painted

reproduction of the infamous

photograph of the uniformed

Pfc. Lynndie England holding a leash tied to the neck of an Iraqi

prisoner who curls naked in a fetal position on the Abu Ghraib

prison floor. This image sent shock waves around the world, as

did the one reproduced in the second panel, a hooded Iraqi prisoner

balancing on a platform with electrical wires attached to his limbs

and genitals.

Such haunting images of humiliating torture reinforced for many

the admonitions of Col. Mathieu in The Battle of Algiers, the famous

film on guerrilla warfare now reportedly in vogue at the Pentagon.

The colonel's words impressed on the audiences of the early 1960s,

as they do to the global multitude today, that the continued presence

of an imperial military where it is not wanted requires it to identify

sources of populist agitation by any means necessary. An ordinary

citizen's support of the occupation, whether in the name of liberation

or in the name of progress, implies his or her tacit acceptance

of all the repercussions of military force, including torture.

Passing these reproductions of domination on the freeway, I was

struck by the imprints of the hand that had transformed their texture

from photographs into painted images. I was also struck by the

words that were written in Farsi to one side of the second panel: "Emrooz

Iraq." "Today Iraq." It is an auspicious caption

that almost reads like an alert on a mobile phone: "This is

Iraq today."

The third and fourth panels in the series represented

the site of pilgrimage in Mecca and the shrine of Imam Ali, the

son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. A quotation attributed to

Imam Ali appeared across the fourth image. It calls upon the believer

to be the enemy of tyranny and a supporter of the victim of injustice.

Following a gap on the wall, a final panel captured three soldiers

on bended knee surrounded by smoke and fire in combat.

The last heavy combat Iranian soldiers saw was the vicious eight-year

war between Iran and Iraq, for which Iran sacrificed the majority

of its male labor force, men who would now be in their thirties,

forties or early fifties. Seen from the perspective of that war,

the messages communicated in the fusion of these five panels seemed

ambiguous at best.

The images arrived as both the bearers of the

latest news -- "Today Iraq" -- and a prescription for

pious living. "Be a force against evil and a defender of the

good." They carried both a reminder of a crucial duty for

the devout and a powerful picture of military retaliation. They

were a broken phrase, an unfinished visual exhortation to an end

open to question.

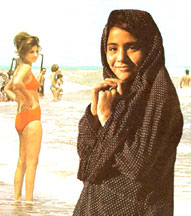

There is little question, however, about the messages contained

in images of female bodies in Islamic cultures circulated by the

global media. Appearing in enlarged photos enveloped by small newsprint,

unveiled women in hair salons enjoy a cut or a manicure. Shots

of Afghan women walking the streets of Kabul without a shroud and

Iranian women in tight, thigh-length overcoats and colorful headscarves

made for Barbie on a camping trip decorate the pages of weekly

newsmagazines.

These images and their pointed captions speak, on

the one hand, of the fruits of another US-led war effort and "the

fall" of the Taliban regime. They show, on the other hand,

a burgeoning scuffle for change -- change conceived in terms of

an imagined democracy in which women appear in the public sphere,

relatively unfettered. This fantasy of Oriental women's liberation

by Western intervention, though centuries in the making, goes little

further than the printed page. Liberals have called the images

of liberated women's bodies propaganda, though in a time of total

war such as ours, one would not have expected otherwise.

MARKER OF MODERNITY

It is important to recall, before proceeding, that women's bodies

have long been politically charged symbols within Iran's national

history, not just in its relations with the West. The decision

of Reza Shah, father of the Shah deposed before the Islamic Revolution,

to mandate that Iranian women remove the veil in the 1930s was

the culmination of one lengthy historical process and the beginning

of another.

The Shahnama, a national epic that versifies the history of Iran

from its beginnings until the Muslim conquest, for example, suggests

a vital role played by women. Mahmoud Omidsalar argues that feminine

symbols, indeed female figures, appear throughout this epic to "arbitrate

all significant instances of transfer of power, be they royal,

heroic or magical."[1] Embodied at times in female literary

and historical characters such as Faranak, Barmaya and the goddess

Anahita, the female body stands at the birth of "all new orders" and

reassuringly watches over moments of transitional trauma.

Reading the periodicals and records of the Iranian constitutional

period (1905-1911) for the parliamentary debates that focused on

the nation's responsibility for the fate of Quchani women and girls

captured or sold to the Turkomans, Afsaneh Najambadi suggests that

gender may be considered a "uniquely structuring category" for

the study of similar transitional moments.

Though largely forgotten

in subsequent renditions of events, the debates concerning the "daughters

of Quchan" were pivotal to the consolidation of the Iranian

parliament and for the constitution of Iran's modern identity.

Indeed, the term vatan defined a nation that was imagined as a

community larger than the familial and the immediate and "inscribed...as

a female body."[2]

In the chronicles, memoirs, modernist tracts

and Iranian travel narratives of the nineteenth century onward,

the female body as mother and as beloved became principally the

metaphorical and ultimately the material battleground for the

inscription of the nation. The female body was, in other words,

a pivot in

Iran's historical transition to modernity.

Consider the unveiled body of the Babi poet Tahirih Qurrat al-Ayn

(Fatemeh Baraghani), who appears in the chronicle of the nineteenth-century

court historian, Muhammad Taqi Siphir, Nasikh al-Tavarikh. Siphir

takes pleasure in an exaggerated description of the poet's unveiled

body, adorned, as he describes it, like a peacock of Paradise beckoning

an audience of desiring men to "kiss those lips of hers which

put to shame the ruby of Ramman, and rub their faces against her

breasts, which chagrined the pomegranates of the garden."[3] The unveiled woman poet is represented in the chronicle as the

object-cause of national desire, a desire that is then condemned

by the force of the law in such a way that the national subject

is hailed to destroy it. Reading this and other nineteenth-century

narratives hermeneutically, it is impossible to pin down what her

particular encroachment on the nation is about. But in the subsequent

recollection of the image of this prototypical Babi in the next

eight decades, it is clear that "the Babi" is indistinguishable

from the modern Iranian subject itself.

Women's associations founded in

the decades after the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 began publishing

newspaper and journal articles in which they addressed unveiling

as a symbol of modernity. Later, in the 1930s, Reza Shah's stringent

unveiling policies saw veiling as a marker of national backwardness

and a measure of women's social retardation. The enforcement of

new unveiling laws sparked many debates about women's education,

progress and women's role in the constitution of Iran as a modern

nation. Women's associations founded in

the decades after the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 began publishing

newspaper and journal articles in which they addressed unveiling

as a symbol of modernity. Later, in the 1930s, Reza Shah's stringent

unveiling policies saw veiling as a marker of national backwardness

and a measure of women's social retardation. The enforcement of

new unveiling laws sparked many debates about women's education,

progress and women's role in the constitution of Iran as a modern

nation. The Babi as an unveiled female body was recovered again

and again in the public and private documents of this era as a

threat to the very constitution of the Iranian nation and, paradoxically,

as the marker of its emerging modernity. What was at stake, it

would seem, is the concept of namus (honor) "which shifted

in this period between the idea of purity of woman ('ismat) and

integrity of the nation."[4]

Until at least the first decade

of the twentieth century, "when women began to claim their

space as sisters in the nation," both 'ismat and national

integrity were subject to male responsibility and protection.

"THE VEIL!" "FREEDOM!"

The generation of largely upper-class, urban, educated female

writers who were born before the establishment of the Islamic Republic

in 1979 are the inheritors of this history. For them, the compulsory

veiling instituted by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his clerical

regime became a key means of illustrating the broader social and

political tensions unleashed by the revolution.

One simple panel

in the Paris-based Iranian artist and writer Marjaneh Satrapi's "graphic

memoir," Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood, stands out

as a forceful representation of this moment of transition and the "cultural

revolution" that began to assume its full force right before

the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988.

On the left of the panel, four women, shrouded in black veils,

with eyes closed, open brows and two arms raised in the air, recite

the words: "The veil! The veil! The veil!" On the right,

facing them, four women, eyes wide open, brows slanting downward

in anger, raise their arms to the words, "Freedom! Freedom!

Freedom!" Satrapi's caption to this panel reads: "Everywhere

in the streets there were demonstrations for and against the veil." (5)

None of the brows on Satrapi's characters are unfurrowed after

this point, with the exception of the panels in which she draws

her young schoolmates playing with the winter hoods they were asked

to knit for Iranian soldiers (97) or again, when she depicts the

girls giggling about the flatulence factor of canned beans sitting

on an empty shelf in a Tehran supermarket during the war. (92)

The eyebrows disappear entirely on the faces of young Marji

and her veiled female friends when they make eye contact with

young

men in an upscale hamburger joint called Kansas. (112) Throughout

the book, the furrowed brows of her characters signal tension

and uncertain transition. They are witnesses to strife.

The hejab (Islamic dress), made mandatory in the new Islamic

Republic to counter, however nominally, the Western cultural impulses

associated with the former Pahlavi regime, and to protect and preserve

the purity of Iranian women, is described in the biographical texts

of Satrapi and Azar Nafisi as "stifling" and "unnatural." In

their works, the Iranian chador (a black, full-length veil) appears

as a new historical marker that would distinguish the ideological

position of "the fundamentalist woman" from the position

of a woman who stands in opposition to the newly established Islamic

regime.

Another panel in Satrapi's graphic memoir emphasizes the ambivalence

many Iranians felt about the social change that immediately preceded

the Iran-Iraq war. Indoors, behind a curtained window, a young

girl named Marji who represents the narrator stands between her

mother and father, looking out onto the street. Together, they

watch a bearded man pass by in trousers and a long-sleeved shirt,

with his wife, in a full chador, holding her young son by the hand.

Before the window, looking out, Marji's father is drawn with

a mustache. His wife, standing slightly bent over, as if despondent,

is dressed in a tight-fitting top and a checkered skirt. She speaks

the words that are seemingly on the minds of the other members

of the family: "Look at her! Last year she was wearing a miniskirt,

showing off her beefy thighs to the whole neighborhood. And now

Madame is wearing a chador. It suits her better, I guess." (75)

These images are images of struggle, embodied as principled positions

in a war against two distinct regimes. They are capsules

in ink

and paper of a particular time and place.

The numerous memoirs and biographies written since the 1979 revolution

are sprinkled with notations on female adornment -- alluding to

everything from the mandatory head covering to prohibitions on

nail polish and lipstick. If these references appear superficial

and at times repetitive, their constant presence gets at the crucial

question that has dominated Iranian politics since the nineteenth

century.

That question, simply put, asks, "Whose nation is

this?" For the women writers, this is a historical question,

one that surfaces from bearing witness to a nation's transformation.

It stems from the recognition that one's own body -- a female body

-- is a fundamental constitutive force in the coming into being

of a new era in national history. The question is localized in

that it asks, "What effects do the things that I embody bring

about in this nation today?"

GENERATIONAL DIFFERENCES

The memoir of Johns Hopkins University professor Azar Nafisi,

Reading Lolita in Tehran, which had spent 36 weeks on the New

York Times bestseller list as of mid-September 2004, engages this question

directly. Nafisi acknowledges in the book that her return to Iran

to teach literature during the post-revolutionary period meant

that, by virtue of her gender, she would be at the center of politics.

Her book, in this sense, follows the trajectory of literature that

bears witness to the processes of change during the revolution

and the first years of the Islamic Republic. She shows the ways

in which the female body plays a pivotal and assertive role in

the formation of the new.

Describing a city battered by war, she writes about the students

who attended her classes during the 1980s and early 1990s to read "the

great books" of the Western canon, including novels by Jane

Austen, Henry James, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Vladimir Nabokov.

Her goal of describing how her female students, sitting in the

private study circle that she founded in 1995, identify their own

plight with the plights of Lolita and Elizabeth Bennet is enough

to capture one's interest.

The writing, too, is gripping. Each

of Nafisi's characters "glows on the page," one reviewer

writes, "illuminated by Nafisi's affection." Most reviews

of the book in the US press are comparably fervent and enthusiastic. "Reading

Lolita in Tehran had a most unusual effect on me," writes

another reviewer. "I didn't want to be interrupted, so I canceled

a dental appointment and a business lunch and missed a deadline.

I read and read and ignored the world. This is what brilliant books

will do; they seize you until the story is over."

As Nafisi herself told the New York Times, however, "People

from my country have said the book was successful because of a

Zionist conspiracy and US imperialism, and others have criticized

me for washing our dirty laundry in front of the enemy." These

are certainly unsettling responses to a book that by all accounts

deserves praise for its style, complexity and all-consuming efficacy.

But how is one to interpret such accusations?

Though some of Nafisi's study circle participants are children

of the revolution, there is a sense in which Reading Lolita in

Tehran is a witness to a period that has passed. As one of Mahnaz

Kousha's female informants in Voices from Iran: The Changing

Lives of Iranian Women explained in a series of interviews conducted

between 1995 and 1997: "The younger generation (born after

1979) is going to be the agent of change.

From the very beginning

when they opened their eyes they saw that women demonstrated on

television. It is correct that all those demonstrators wore black

chadors. What is more important is that they were all women, demanding

something. This generation has seen women playing an active role

and has accepted that.... Veiling is not a problem for those children

who were raised with it. It is not going to stop them. I believe

a piece of material is not going to stop women's progress."[5]

Kousha's

informant underscores the ability of younger women to demand

and bring about social change regardless of what the outside

world perceives as insurmountable restrictions. What was encumbering

and unnatural to Nafisi's pre-revolutionary generation is now

unremarkable to many, if not all, of the generation that has grown

up knowing

nothing but the mandatory veil. The emphatic outrage over the

circumstances of women when Islamic rule was freshly established

has become almost

mute.

"When we had this secret class in Tehran," Nafisi

told the Washington Post in December 2003, "we felt

utterly helpless." But not all Iranian women feel helpless

after the limited openings for social and political activism offered

by the

period of Khatami's presidency, and indeed Nafisi is hardly unaware

of the powerful presence of women in Iranian society today.

Of

the Nobel Prize-winning women's rights activist and human rights

lawyer Shirin Ebadi, she wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "As

a woman activist she did not have to look to other countries for

role models: She could rely on the tradition created by many courageous

Iranian women before her, who, for over a century, had fought despotism,

opening political, cultural and social spaces for Iranian women." In

the same interview with the Washington Post, she said of women

living in Iran, "They are persistent. This is bigger than

politics. These women just refuse to give up."

TOTAL WAR

Moreover, it seems undeniable that Reading

Lolita in Tehran and

its author have been promoted, at least in part, to fulfill the

ends of total war. Although human rights violations are an ongoing

and urgent concern in the era of President Mohammad Khatami, whose

government came to power by democratic election in 1997, after

the point at which Nafisi's book ends, the restoration of such

rights is not the driving force of the total war in which Nafisi's

book has been embedded.

Former Marine Adam Mersereau explains

the concept of total war in the National Review. It is a war "that

not only destroys the enemy's military forces, but also brings

the enemy society to an extremely personal point of decision, so

that they are willing to accept a reversal of the cultural trends

that spawned the war in the first place." Former Marine Adam Mersereau explains

the concept of total war in the National Review. It is a war "that

not only destroys the enemy's military forces, but also brings

the enemy society to an extremely personal point of decision, so

that they are willing to accept a reversal of the cultural trends

that spawned the war in the first place."

While a total war

strategy does not have to "include the intentional targeting

of civilians," sparing them "cannot be its first priority.

The purpose of total war is to permanently force your will onto

another people." The purpose of the total war that is the

US-led "war on terror" is to force "the grid" onto

a culture that is, at its best and at its worst, ambivalent to

it.

For some time before and after the publication of her runaway

bestseller, Nafisi was being promoted alongside proponents of total

war by Benador Associates, which arranges their TV appearances

and speaking engagements and helps to place their articles in the

top newspapers. Such neo-conservative luminaries as Richard Perle

and James Woolsey, who notoriously referred to the war on terror

as "World War IV," are still clients of the agency.

In

September, their agent Eleana Benador traced the cognitive links

the neo-conservatives draw between the war and Middle Eastern women

in a posting "From Eleana's Desk" on the agency's website:

"One

of the most memorable experiences [of the 2004 Athens Olympics]

was to watch the Afghan woman participating in one of the races,

as well as an Iraqi woman. They didn't go far, they were among

the last ones. But, watching them, I couldn't avoid thinking:

'We are winning!' Yes, we are winning over extremism, whether

religious

or secular. More accurately, we are starting to win. The road

ahead is still a long one, but the beginning is already giving

results.

We have rescued from the hands of those extremists these women

who have regained their status as human beings, and who are

learning now what it is to be treated with respect and dignity."

In Nafisi's acknowledgements, finally, Princeton University emeritus

historian Bernard Lewis is thanked as one "who opened the

door." Though one would hope that she testifies here to the

gentleman's chivalry and good breeding, one fears that there is

more to it. Lewis is the eminent theorist of civilizational decline

in the Islamic world who has reportedly briefed Dick Cheney. Books

like his own bestseller What Went Wrong? (2002) are the

ahistorical scaffolding upon which the neo-conservative hard core

of Perle

and Woolsey hang their policy prescriptions.

Take, for example,

this statement by Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, a

leading neo-conservative inside government: "Bernard Lewis

has brilliantly placed the relationships and the issues of the

Middle East into their larger context, with truly objective, original

and always independent thought.

Bernard has taught [us] how to

understand the complex and important history of the Middle East

and use it to guide us where we will go next to build a better

world for generations to come." But what does this complex

and important history amount to? As University of Michigan history

professor Juan Cole observes in a generous review of Lewis's book, "[Lewis]

is not writing analytical history here, with a view to explaining

particular problems by isolating independent variables. He is writing

moral history, which is tautological. He seems to insist on erasing

any successes [Muslims] have had, and to imply that the Muslims

have failed because they are failures."[6] Failures.

MILK ANGER

After my return from Tehran in the summer, I received a photograph

of the panels I had seen on the Sadr freeway. The fifth of the

six panels had gone up to fill the gap on the wall. There are two

men in it. One is laying face down on a red carpet, and the other,

sitting next to him, looks out of the frame toward the sixth panel

depicting the three men engaged in military combat. The caption

on the left side of the fifth panel reads: "Dirooz Filistin." Yesterday

Palestine.

While the messages and meanings of the images of torture in US

jails in Iraq are being muted in the global media with visual rhetoric

that justifies the occupation, and does so by promoting images

of women's bodies that have been liberated in hair salons, the

Iranian government is promoting images of prison tortures toward

different ends. These images of humiliating violence in US-occupied

Iraq are hung in close proximity to images that remind the viewer

of the inequities of Israeli occupation in Palestine.

It is likely, to my mind, that Nafisi's efforts converge on a

will to institute a transnational feminist ethics that is concerned

with the lives and conditions of women elsewhere. But if this is

so, a consistently ahistorical analysis of Iran -- one that does

not distinguish between past and present -- cannot be the rallying

call for efforts on behalf of Iranian women today. In the era of

total war intent on the reversal of cultural trends through external

force, Reading

Lolita in Tehran as a representation of the state

of current affairs is an undiscriminating gesture. It performs

like a wound-up metal monkey on wheels as the warmup act for more

theater of unprovoked war and another occupation.

A transnational feminist practice intent on the

Middle East is better served by focusing on the question that has

long kept the region so distraught, and that has contributed to

a colére du lait (milk anger) that, like milk,

boils into sudden rage when heated. This question is the question

of occupation.

Modifications in the status of women in relation to the nation-state

are handled more ably by internal forces of change. That is the

judgment of history and a judgment in ethics. A transnational feminist practice intent on the

Middle East is better served by focusing on the question that has

long kept the region so distraught, and that has contributed to

a colére du lait (milk anger) that, like milk,

boils into sudden rage when heated. This question is the question

of occupation.

Modifications in the status of women in relation to the nation-state

are handled more ably by internal forces of change. That is the

judgment of history and a judgment in ethics.

Author

Negar

Mottahedeh teaches in the Program in Literature

at Duke University. This article was first published in Middle

East Report (September 2004). Mottahdeh thanks Shiva Balaghi,

Mazyar Lotfalian, Mana Rabiee and Ramyar Rossoukh

for

providing

valuable

materials

for

this essay. "Off the Grid" is dedicated to Antonio

M. Arce.

[1] Mahmoud Omidsalar, "'Waters and Women,

Maidens and Might': The Passage of Royal Authority in the Shahnama" in

Guity Nashat and Lois Beck, eds. Women in Iran: From the Rise

of Islam to 1800 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004), p. 171.

[2] Afsaneh

Najmabadi, The Story of the Daughters of Quchan: Gender and

National Memory in Iranian History (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University

Press, 1998), p. 182.

[3] Siphir is quoted

in Abbas Amanat, Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the

Babi Movement in Iran (Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press, 1989), p. 321.

[4] Ibid., p. 183.

[5] Mahnaz

Kousha, Voices from Iran: The Changing Lives of Iranian Women (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2002), pp. 227-228.

[6] Juan Cole, "Review

of Bernard Lewis's What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern

Response," Global Dialogue 4/4 (Autumn 2002). See also Adam

Sabra, "What Is Wrong with What Went Wrong?" Middle

East Report Online, August 2003.

*

*

|