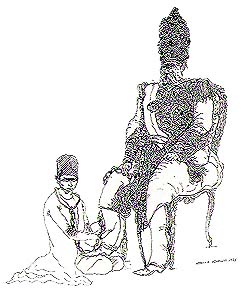

"The King and I" by Ardeshir Mohassess.

From "Life in Iran".

Copyright Mage Publishers

The King and I

The tradition of Persian kingship

March 6, 1998

The Iranian

From

"The

Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation" by Sandra

Mackey (Penguin Group, 1996).

From

"The

Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation" by Sandra

Mackey (Penguin Group, 1996).

The exalted grandeur of Persian kingship, faded by almost two decades of Islamic government, still dwells in Iran. It can be seen in a relief on the tomb of Darius at Naqsh-e-Rustam in which the king stands on a two-layered throne supported by his Persian and foreign subjects; in illustrations of the timeworn arch of the palace of Taq-e Kasra at Ctesiphon, the great memorial to the Sassanians; in the jewel-encrusted Peacock throne on which all Iran's kings since the eighteenth century have sat; and in Gulistan Palace in the heart of Tehran, the legacy of the Qajars.

But it is in the archives of Iran's last king, Mohammad Reza Shah, where the nature of Persian kingship most powerfully expresses itself. Here photographs rather than jewels and architecture portray the glorified position of the Pahlavi king as a powerful authority figure commanding the suppliance of his subjects. In 1963, a peasant receiving a deed to a bit of land lies prostrate before the shah. In late 1977, an army general wrapped in gold braid with a sword strapped to his side walks toward the king crouched in a half kneel, his hands held together in a gesture of prayer. On Noruz of 1978, high-ranking government officials line up to bow and kiss the hand of their sovereign just as their predecessors once paid obedience to the absolute authority of the kings of Persia.

The institution of Persian Kingship spans the history of Iran from the Achaemenians of the fourth century B.C. through the Pahlavis of the twentieth century A.D. During that great arc of time, a core element within Iranian identity linked Iran's heroic past and its exalted civilization to monarchical rule. Perhaps more than any other people, Iranians perceive their history as a history of their monarchs. Under their rule, the nation swept to every victory and rallied after every defeat. In culture, as in politics, kings fostered poetry and painting, carpets and tiles, intricate works of gold and massive structures of architectural art. Whether beneficent or tyrannical, Persian kings sat on the throne enveloped in the Iranian expectation of imperial rule.

The Iranian ideal of monarchy comes out of the ancient Zoroastrian concept of a king governing hand in hand with Ahura Mazda. Thus he derives his authority from possession of farr, a sign of favor bestowed on those who stand on the side of good against evil. Conversely, a king who leaves the light to enter the darkness sacrifices the farr and with it his authority. Evidence of who possesses the farr and, therefore, the right of leadership takes the form of personal charisma.

In the Iranian concept of leadership, a leader possesses charisma because he is endowed with supernatural powers, or at least exceptional qualities, that set him apart from ordinary humans. He commands a special grace, an otherworldly quality that engenders trust, commitment, and an irresistible desire to follow. The reality that charismatic figures bearing a new dynasty often appeared during pivotal points of history to sustain the Iranian nation reenforced the concept of the hero king. Thus monarchy became a function of personality where authority flowed to the charismatic leader rather than being imposed by the institution of the throne.

Furthermore, this ideal and expectation of charismatic leadership constitutes one of Iranian culture's defining characteristics. Although historically, applicable to kings, charismatic leadership never has been limited to monarchs. From time to time in Iranian history, a king has sat on the throne while power surged to someone else. Within the twentieth century alone, the Iranians saw the prime minister Mohammad Mossadeq in the early 1950s as the charismatic leader. In the late 1970s, it was the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. But it was kings who usually filled the role of charismatic leader.

... The political system ruled by the all-powerful king reflected the highly-structured society that dated to Iran's origins. The Achaemenians ruled over a population divided by the tasks necessary to the overall strength of the community and the empire. The Sassanians even more precisely ranked and graded society in the interests of the king and state. Cracking during the Arab conquest, the hierarchical order underwent repair and codification under the Safavids.

Reenforcing the traditional social pyramid, the administration of Safavid Iran assigned a title to every occupation and precisely ranked every position in the state from the shoemaker up through the entourage of the shah. At the top, the Safavid elite comprised the same groups that had constituted the ruling class of Iran for centuries. Thus the king, his extended family, the landed aristocracy, the khans of the important tribes, members of the ulama who supported the shah, the upper echelons of peasants stayed locked in the ancient hierarchy.

In this system of absolute monarchy and rigid social division, every level of society harbored its own insecurities. Yet insecurity is exactly why absolutism survived. It was the range of catastrophes threatening to life, property and psyche that led peasants clustered in their villages to welcome rulers strong and tyrannical enough to scare everyone else into submission. This same desperate need for security from enemies within and without carried over to the people of the towns and cities. As a result, fear kept in motion the dynamics of feudal politics: Make alliance with whoever is strong; promote powerful kings; surrender nebulous personal freedom in return for some promise of stability.

... Yet the great paradox of Iranian monarchy is that the ideal of just rule by a charismatic leader stubbornly survived for 2,500 years despite the harsh realities of a political and social hierarchy in which one level inflicted injustice on the level below. Through all the tyranny and despotism, Iranians never accepted man's inhumanity to man as either natural or inevitable.

About the author

Sandra

Mackey has written on the culture and politics of the Middle East for such

periodicals as the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal,

the Christian Science Monitor, and the Chicago Tribune. Appearing

as a guest expert on Nightline, ABC News with Peter Jennings,

the National Public Radio, she also served as a commentator for CNN during

the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. She is the author of three previous books:

The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom, Lebanon: Death of a Nation,

and Passion and Politics: The Turbulent World of the Arabs. She

lives in Atlanta, Georgia. (Back to top)

Sandra

Mackey has written on the culture and politics of the Middle East for such

periodicals as the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal,

the Christian Science Monitor, and the Chicago Tribune. Appearing

as a guest expert on Nightline, ABC News with Peter Jennings,

the National Public Radio, she also served as a commentator for CNN during

the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. She is the author of three previous books:

The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom, Lebanon: Death of a Nation,

and Passion and Politics: The Turbulent World of the Arabs. She

lives in Atlanta, Georgia. (Back to top)

Related links

* Also from Sandra Mackey's "The Iranians"

- Cyrus

the (not so) Great

* Our

leaders - Photos of the Shah and the Ayatollah.

* Democracy

or Theocracy (in Persian) - Ferdowsi's poetry sheds lights on ancient

political thinking. Dr. Mahmoud Sadri

* Bookstore

* Cover stories

* Who's

who

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved. May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

|

|

|