|

>>>

NEXT (16 total)

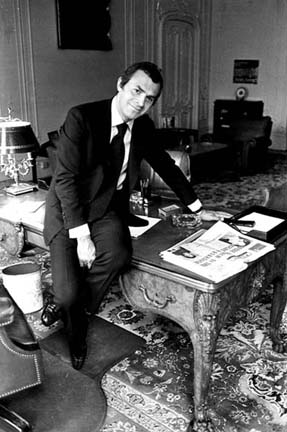

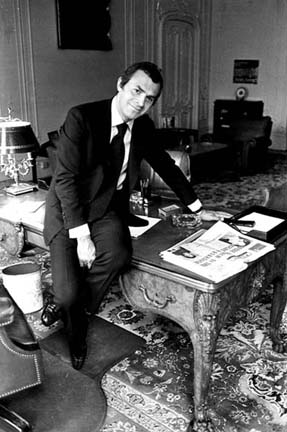

Iranian Ambassador Parviz Radji posing in his Embassy office for

Daily Express photographer Hilaria McCarthy (London, 23 August 1977)

>>>

NEXT (16 total)

Ex-ambassador

"I was never one of those people who admired the Shah"

By Cyrus Kadivar

July 30, 2002

The Iranian

The Shah's last ambassador to London greeted me behind his apartment door. "Come

in," he said, shaking my hand with a very firm grip. At sixty-six, he was a

handsome man, very tall and narrow-framed. He cut a dashing figure in his open shirt,

blue cardigan and white slacks. Unlike most of his older photographs he was wearing

glasses but his face and expressions were distinct as ever.

Taking my coat he led me politely to the beautifully furnished sitting room. I sat

down on a beige sofa overlooking the tall windows with their floral curtains.

"Would you care for some wine?" he asked in a rather melodious voice. I

accepted his offer graciously and while he left the room momentarily I cast my eyes

at the lovely room searching perhaps for clues that would shed light on this interesting

man.

There was a certain understated elegance that was rarely seen in a Persian home.

Although it was tastefully decorated there was nothing ostentatious about the place.

The white shelves, unlike the ones I had seen in the hallway, were devoid of books

and boasted some ancient pottery items. Hanging on the walls were a few original

paintings mostly with Oriental themes.

The fireplace was unlit. In front of me was a low coffee table with a book on Qajar

Persia and several precious items among which I observed an Indian worry bead with

miniature ivory skulls. On my left, on a smaller table, a few stacked books among

which I recognised Roloff Beny's A

Bridge of Turquoise.

Parviz Radji smiled broadly as he handed me a glass of white wine, then glided towards

a chair. He sat down and crossed his long legs.

The silence in the former ambassador's residence was deafening except for the occasional

telephone ring and soft-footsteps in the kitchen. There was something too quiet about

this place, an awkwardness imposed by my curiosity.

"To your health," he said. He took a sip then placed the glass on a wooden

gun box.

I watched him with almost boyish enthusiasm. His gaze was friendly, almost shy. He

seemed devoid of any cautious scrutiny one would expect from an experienced diplomat.

Although I had never met him before I was familiar with his colourful past.

Accredited to the Court of St. James's as Imperial Iran's Ambassador from 4th June

1976 to 26th January 1979, Parviz Radji had made no secret of the fact that his two

patrons, the late Amir Abbas Hoveyda and Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, had been behind

his golden appointment.

So far as I could deduce from his witty and revealing diaries published in 1983 under

the title, In

the Service of the Peacock Throne, Parviz Radji had been uniquely placed

to witness the final death throes of the Shah's regime.

From the start of our talks I openly explained my reasons for wanting

to meet him. After all he had been a witness to many things. He had met the Shah

during the last years of his rule and been privy to many of the most important decisions

made by the Iranian Court and Government. As ambassador he had led a highly exciting

life in British and Iranian high society. He was also a link to a bygone era. From the start of our talks I openly explained my reasons for wanting

to meet him. After all he had been a witness to many things. He had met the Shah

during the last years of his rule and been privy to many of the most important decisions

made by the Iranian Court and Government. As ambassador he had led a highly exciting

life in British and Iranian high society. He was also a link to a bygone era.

We also had something in common. Throughout that turbulent period, which ended with

the fall of the Shah's regime and the triumph of Ayatollah Khomeini, Radji had kept

a diary, both social and political. I too had kept one albeit a modest one during

the 1979 revolution. But that's where our similarities ended. When the storm broke

he was in his forties, an educated, Iranian diplomat in one of the world's exciting

capitals, and I simply a school teenager in Shiraz.

Radji had witnessed the revolution from afar and I had experienced the convulsion

and mob violence first hand in Iran. The revolution had ended his career and made

me an exile. It was hardly surprising that we should have talked about the revolution,

arguably the most important event of the 20th century - and our lives.

Listening to Radji I was intrigued by his manners and impeccable English. At times

he sounded like Sir Anthony Parsons, Britain's last ambassador to Imperial Iran.

In the soft light the dark shadows on his face tricked me into seeing a certain physical

resemblance to an actor. I recalled reading in his diaries that the late Ava Gardner

whom he had met a few times thought he looked like James Mason.

Only when he slipped into Farsi, and that was occasionally, did I catch a glimpse

of his Persian self. There was nothing pretentious about him except a lasting impression

that over the years he had grown accustomed to the ways of the British.

Born in 1936, Parviz Radji was the son of an orthopaedic surgeon. He had been educated

first in Iran and America, then in England where he read Economics in Cambridge.

In 1959 he had returned to Iran brimming with enthusiasm

and impatient to serve his country. At twenty-three he had joined the National Iranian

Oil Company (NIOC) as a trainee analyst where he met and worked for Hoveyda. In 1959 he had returned to Iran brimming with enthusiasm

and impatient to serve his country. At twenty-three he had joined the National Iranian

Oil Company (NIOC) as a trainee analyst where he met and worked for Hoveyda.

In 1965 Hassan Ali Mansour was shot dead in front of the Majlis by an Islamic fanatic

and the Shah appointed Hoveyda as the new prime minister. When Hoveyda asked Radji

to join him at his exalted office he accepted at once. It was an opportunity he could

not refuse. Radji remained as Hoveyda's private secretary until 1969. Those years,

he recalled, were to be among his happiest.

It was a period of feverish activity. Working for the second most powerful man in

the land, Radji was able to witness at first hand the exercise of political power,

the wielding of personal influence, and the bestowal of official patronage.

"I respected Hoveyda as an individual and admired him as an administrator,"

Radji told me. "Scrupulously honest, he was an educated and highly cultivated

man. He was both a demanding and a rewarding boss, and I should like to think I learnt

much from serving under him. There was never anything arrogant about him."

Clever and cunning, friendly and approachable, Hoveyda was unique amongst Iranian

politicians. If not particularly humble, he had the capacity to laugh at himself.

His charming and uncommon personality made a lasting impression on Radji who became

his protege. Through him he met Princess Ashraf who represented Iran on the UN Commission

for Human Rights and presided over innumerable charities.

From 1970 to 1973 Radji worked for Princess Ashraf, the Shah's twin-sister, at the

United Nations and elsewhere before returning to serve Hoveyda as Special Adviser

to the Prime Minister. In early summer 1976 he was posted to London.

Within the first days as Ambassador, Radji was plunged into something of a nightmare.

His predecessor, Mohammed Reza Amirteymour, a distinguished career diplomat who had

run a big gambling debt, had been found dead in his flat at Ennismore Gardens. But

as his exciting diaries reveal, Parviz Radji was soon busy entertaining guests at

the Imperial Iranian Embassy at Princes Gate.

On 8th June 1976 the Iranian Ambassador gave an official Embassy dinner for Princess

Margaret and Princess Ashraf while 50 demonstrators gathered on the pavement opposite

the Embassy Residence denouncing the Shah and brandishing placards showing people

alleged to be political prisoners in Iranian jails.

Four days later, Radji, attended the Trooping the Colour ceremony, receiving King

Constantine and Queen Anne-Marie of Greece for lunch with Princess Ashraf at the

Embassy. On the same day Radji left for Oxford to inspect a library named after the

Princess. At Wadham College they were faced by a hundred masked demonstrators chanting

the most ferocious obscenities and pelting their car with eggs. It was an inauspicious

beginning for an ambitious diplomat.

Not unlike Mirza Abul Hassan Khan, Persia's 19th century ambassador to London, Parviz

Radji, was an intelligent, observant and cultured man although perhaps less dazzled

by English life than the former. He kept a diary and filled his days with carrying

out the Shah's instructions, making calls or receiving visitors. As the Shah's Ambassador,

Radji had been the toast of London Society. His unique position allowed him to meet

with members of royalty, aristocrats, diplomats, politicians, businessmen, journalists,

writers and actors.

In his capacity as Safir, or Ambassador, Radji represented the Shah's personal

diplomacy, enjoying the honours and attention that the role offered him.

By the mid-seventies Iran had attained a position of international respect and a

stable pattern of foreign relations. Iran's Foreign Ministry had developed a well-trained

and experienced diplomatic staff of around 1,200 people and positioned itself as

one of the country's most modern and efficient bureaucracies.

In Britain the Foreign Office's attitude towards the Shah reflected the importance

of Iran as a source of crude oil, as a strategic partner in a turbulent part of the

world, and as a rapidly growing market for British exports, both civil and military.

Iran's prestige was reflected in her confident ambassadors.

But within a year Radji was agonising over his role. The high honour, the lavish

house, the Rolls Royce and the Dom Perignon, did not come without a certain moral

price. Not a day passed without coming across a newspaper article criticising the

Shah's "dictatorial regime", a BBC report about the "economic bottlenecks

and power cuts in Tehran", or a snide remark by one of his distinguished English

guests, about "corruption in Iran" or the overrated secret police.

As the Shah's ambassador Radji remained a true diplomat but privately he questioned

himself whether it was courage and loyalty to turn a blind eye to the darker aspects

of the imperial regime and to go on enjoying the innumerable charms of London life?

It was, I believe this reccurent crise de conscience, that eroded Radji's

faith in the Shah's survivability although at times he comforted himself with the

alternatives. The mullahs or the communists would be worse than the monarchy, he

told himself. All this must have weighed heavily on his mind as his diaries reveal.

Despite his self-reproach he had no choice but to present the official line.

"Each day I felt more humiliated," he confessed. "This does not mean

I was not grateful to the Shah for my posting. I do not deny the major achievements

under the Pahlavi regime nor many of our foreign policy triumphs abroad. But the

system was such that there was no room for individual expression. The Shah liked

young and educated people but he often disregarded those older diplomats like Entezam

who had a wealth of experience."

"Did you like the Shah?" My question made him grin. "I was never one

of those people who admired the Shah," Radji replied then after a momentary

reflection added, "but I did fear him."

"In what way?" I asked sipping my wine. Radji straightened his back in

his chair and said, "There was always the worry that something said or written

by me with the best intentions might be taken by His Majesty as offensive, and so

terminate my appointment, and even bring my career to an end in disgrace."

According to Radji the imperial regime was engulfed by paranoia. "It permeated

everyone from the Shah down to his government ministers," Radji told me. At

times this led to some strange instructions. One day, Radji received a top secret

cable from Tehran. He was to go and visit Madame Tussauds and see for himself

whether reports of an unflattering wax statue of the Shah were true.

"I decided not to use the Rolls Royce with the diplomatic plates," Radji

told me in an amusing tone. "My chauffeur drove me to Madame Tussauds in a less

obvious car. Once there, I slipped inside the museum and headed straight to the Grand

Hall, containing a collection of royalty, statesmen, and world leaders."

Radji took a look at the Shah's wax statue and returned to the Embassy and sent his

report.

"I wrote that while His Majesty's wax statue was a poor imitation," Radji

recounted, "it was in no way any worse than those of Queen Elizabeth, King Hussein

or any other leader. I'm sure Hoveyda must have laughed his head off when he saw

my report. He knew better than anyone how to read between the lines."

By 1978 it was clear that the Shah's regime was in trouble. As the clouds loomed

larger and darker on the political horizon, Radji's initial attempt to pose as a

disinterested observer of the London social and diplomatic scene was abandoned. The

daily cables from Tehran became more urgent. His Majesty's Ambassador was instructed

to monitor the BBC Persian Service daily, determine instances of tendentious reporting,

and protest vigorously on every occasion.

On 17th April, Iran's Foreign Minister, Abbas Ali Khalatbary arrived in London where

he was met at the airport by the Iranian Ambassador. After a lukewarm cup of coffee

at the Alcock and Brown suite, the two diplomats drove to Claridge's.

Later the kindly and soft-spoken Foreign Minister told Radji that he intended to

complain to David Owen about the tone of the BBC Persian language broadcasts. Two

days later they attended the British Foreign Secretary's lunch for CENTO Ministers

at Lancaster House. During a break, while Radji was standing in the hall he was approached

by David Owen, followed by Khalatbary, who in his rather tactful manner raised the

vexed subject of the BBC.

Owen burst out laughing. "I agree with everything you say," he replied,

"but there isn't a thing I can do about it. The BBC is independent of the Foreign

Office!"

After lunch, Radji returned to the Kensington Embassy, angry and humiliated by what

had been said about the BBC. Despite his profound respect for Khalatbary, Radji had

felt pained by the spectacle of the Foreign Minister's sensitivity to a 15-minute

daily analysis of political events in Iran. When Khalatbary came to dinner later

in the evening, Radji asked him to come upstairs for a minute to read a cable he

had prepared to send to His Imperial Majesty.

True to form, Khalatbary read the cable with an impassive, inscrutable expression,

saying he had no objections, but adding that he didn't feel particularly sensitive

or vulnerable to what the British Broadcasting Corporation said. "I know,"

Radji had replied, "but it's not you I have in mind, Sir."

"His Majesty was a great conspiracy theorist," Radji admitted. "He

did not trust the British who had overthrown and exiled his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Even at the height of the revolution he blamed the BBC. He was extremely sensitive

to Amnesty International and foreign press reports about alleged human rights abuses

in Iran. I was naturally expected to defend the imperial regime."

In August 1978, Radji had gone to Tehran for what turned out to be his last visit.

On 5th August, in an unprecedented move, the Shah went on television and promised

to lead the country towards "100% free elections" and declared that all

political parties, except the Tudeh, could register without fear of intimidation.

On the same day, Radji lunched with Hoveyda at the official residence of the Court

Minister. Complimenting him on his performance in London, Hoveyda described in his

jolly way how much he had enjoyed Radji's mischievous cables. While the caviar was

being served, they spoke candidly of the situation in the country.

"The Government is paralysed," Hoveyda confessed. "Rastakhiz is dead

and buried, and policy is non-existent." He went on to say that His Majesty

was more willing to listen to advice.

Three days later, Radji flew to Nowshahr for a briefing with the Shah at his Caspian

resort. After two identification checks a car drove him to the end of the pier, where

he disembarked.

The Iranian Ambassador, accompanied by Education Minister Manuchehr Ganji, were led

to a small waiting room with its air-cooler on full blast. Some Imperial Guard officers,

and one or two civilians, stood up as they entered, and tea was served.

At about 10:15 a.m. Ganji was summoned. While he waited for his turn, the Ambassador

shuffled his papers and reviewed the important matters he wished to raise.

An hour later Radji's name was called. The Shah, wearing a sports shirt and shorts,

greeted his London ambassador in the middle of a large room. As a mark of respect

the Ambassador bowed and kissed the emperor's hand while Beno, the huge great Dane

sat in the corner. Contrary to the current gossip, the Iranian Ambassador found the

Shah looking well but concerned by the inflammatory utterances of the mullahs and

once again questioning the effectiveness of his liberalisation policy. The audience

lasted for just under an hour.

In his talks with high government officials Radji found everyone in a subdued, dejected

mood. On 19th August, Radji met Hoveyda for what was to be their last meeting.

Hoveyda assured him that the Shah was determined not to abandon the process of democratisation

but was critical of the Amouzegar Government's vapid inactivity.

For many years government officials, generals and diplomats had served as instruments

of the King. To all intents and purposes, the Shah was the regime: monarch and state

had become virtually synonymous. The transition from autocracy to democracy was proving

a difficult challenge. "His Majesty," Hoveyda continued despairingly, "finds

it impossible to keep out of the limelight." Finally they embraced each other

in the Iranian way and said goodbye, promising to stay in touch.

I reminded Radji about a nice passage in his book describing a delightful scene at

a friend's enchanting country home before he left Tehran. Conjuring that vodka induced

evening at Pounak, I sensed that Radji still felt nostalgic for Iran.

Where else in the world, he admitted, would one find the same Persian nights?

The spectre of Khomeini continued to cast a dark shadow. At the Iranian Embassy in

London Radji continued to keep up appearances determined to set a good example to

his staff. Sometimes he would lock himself for an hour in his room, pace up and down

the magnificent Kerman carpet adorning the floor of the huge office, and lecture

himself on the sterling qualities of steadfastness and courage, on the need to suppress

his mounting anxieties. During the final days, he fought a valiant but losing battle

in defending the Shah.

Part of the problem was that the emperor had over the

years antagonised certain members of the British media. Either through vanity or

timidity, the Shah had projected a loveless, severe, power-obsessed image. The Western

press exaggerated these attributes. Part of the problem was that the emperor had over the

years antagonised certain members of the British media. Either through vanity or

timidity, the Shah had projected a loveless, severe, power-obsessed image. The Western

press exaggerated these attributes.

"The Shah was really a man of simple tastes," Radji reminded me. "He

was in fact, a military man at heart, in his element in an atmosphere of military

discipline."

Contrary to appearances, Radji explained, the Shah's lifestyle was devoid of luxury.

Ever since those lavish celebrations at Persepolis, the media had portrayed him as

extravagant. But he was a shy man, which did not allow him to come out of his shell,

in his contacts with people, to show warmth and affection.

"All this may give the wrong impression that the Shah was a harsh and unapproachable

man," Radji said. "True, at times he appeared arrogant. I still have a

tape of one of his controversial interviews with the BBC television. It was embarrassing

to watch him lecture the Western governments about their laziness and economic greed.

Personally, we were never on the same wavelength."

Why did the Shah fall? Why did the mullahs gain power? Why did the West abandon a

regime that had seemed invincible? What was the role of the BBC?

These questions still haunted us. Pontificating on the roots and causes of the Islamic

revolution that overthrew 2,500 years of monarchy in 1979 was second nature to us.

In hindsight we agreed that the late Shah's fall from power had been inevitable.

On 16th January 1979, the same day when the Shah left Iran, Mr Mirfenderski, Prime

Minister Bakhtiar's Foreign Minister, phoned Radji to tell him that his days as His

Imperial Majesty's Ambassador to London were over. As soon as he hung up, Radji sent

off a letter to the Foreign Office informing them of his new circumstances.

In his diaries, Radji described how he had spent the next few days packing his personal

belongings. Suddenly, the gold-braided uniform, the white gloves, the ceremonial

sword in its black velvet scabbard, the plumed hat and the decorations, all seemed

out of place, museum pieces evoking recollections of a bygone era.

On 26th January 1979, after two years, seven months

and twenty-two days as His Imperial Majesty's ambassador to London, Parviz Radji

left the Iranian Embassy. On 26th January 1979, after two years, seven months

and twenty-two days as His Imperial Majesty's ambassador to London, Parviz Radji

left the Iranian Embassy.

We had spoken for three hours. Parviz Radji got up and went out of the sitting room

returning a few moments later with photocopies of two articles he had written. The

first one printed in February 2002 in The Moscow Tribune was a review of Laurence

Kelly's book, Diplomacy and Murder in Tehran, and signed curiously,

Parviz C. Radji, Former Imperial Persia's Ambassador to London.

The second one published in 1989 in The Spectator was entitled "Seeking

somewhere to die" a review of William Shawcross's book on the late Shah's

final days. He seemed moved by my earlier description of the Shah's tomb in Cairo.

He was grateful to the late Sadat for having treated the dying emperor with rare

dignity. "How did you feel about the Shah's end?" I asked rather gravely.

Radji returned to his chair and looked at me sadly. "I felt terrible, even sympathy

for him," he said. "There is a photograph of the Shah in Panama, you know

the one where he is sitting beside a powerful radio, his face and body wracked by

illness. I know that he never quite accepted what happened to him. Even in exile

he was still talking about his White Revolution. That was his tragedy."

I was perfectly aware how much Radji had been torn between his loyalty to his king

and country and the growing realisation that the Shah's regime was doomed inevitably.

His feelings towards Empress Farah were warm and affectionate.

"How would you describe the Pahlavi era to my generation?" I asked curiously.

"It was the best of times and it was the worst of times," he said in a

Dickensian tone of voice. How ironic, I thought. A few hours ago on my way to him,

I had caught my English cab driver reading A Tale of Two Cities, a revolutionary

masterpiece. Sometimes life can be full of the strangest coincidences.

The Ambassador stood up and led me towards the far corner of the living room. On

a small console lit by a lamp was a framed photo of Hoveyda with his smiling, chubby

face, unmistakable arched eyebrows and his trademark orchid in his buttonhole.

Radji had been devastated by the news of his arrest, trial and brutal murder by the

revolutionaries on 7th April 1979. "Hoveyda would never have accepted to live

in exile," he told me with a deep sigh. "He was convinced of his innocence.

He died the way he lived, courageously and with a clear conscience."

Compared to most of his colleagues Parviz Radji was more fortunate than others. When

the monarchy fell he was in England. That probably saved his life. The revolution

dealt an irreparable blow to Iran's hard earned diplomatic successes and proved most

calamitous for the Ministry. Some of Radji's Embassy colleagues were dismissed, a

few stayed on and many returned to Tehran.

Numerous ambassadors who had graduated from leading universities around the world

were also cashiered and, in some cases, arrested, tried and imprisoned. The former

Iranian Foreign Minister Khalatbary, a seasoned and internationally respected diplomat,

was shot three days after Hoveyda's murder. All these sad memories seemed to belong

to another time. It was already getting dark outside.

Looking back to his days as one of London's most colourful ambassadors Parviz Radji

remembered it as the most fascinating, instructive, agonising, frustrating and, at

many a moment, enjoyable time of his life. Things are different today.

These days Radji prefers a comfortable and less hectic lifestyle. He still plays

a game of tennis and the occasional bridge with his circle of friends. He also continues

to enjoy the friendliness and civility of the British towards him. As for Iran, he

still hopes it will adopt a wiser foreign policy and return to humane civilised values.

Only then may his country emerge from the hardships of the last two decades.

Before taking my leave, I thanked His Excellency for his time and asked him whether

I could one day write an article about him. "It would be somewhat a sketch of

your past and present life in the context of our interesting discussions," I

said.

"Sure, but I am not saying this out of pure vanity," he said laughing.

He placed a friendly hand on my shoulder. "We will be in touch," he said

following me to the door.

The Shah's last ambassador to London handed me my coat. I shook his hand and wished

him well. I went down the stairs passing a young lady standing beside a pram with

her sleeping child. I opened the door and heard it close firmly behind me. Outside

it was night and the lights on the Chelsea Bridge sparkled.

Several months later I phoned His Excellency to put

the final touches on my story. He was gracious enough to allow me to go ahead with

it making no attempts to change the text substantially. He had patiently read my

draft and made few minor suggestions. Then in a modest tone he said, "I am not

sure what it will add to what we already know. Anyway, London is full of ex-ambassadors." Several months later I phoned His Excellency to put

the final touches on my story. He was gracious enough to allow me to go ahead with

it making no attempts to change the text substantially. He had patiently read my

draft and made few minor suggestions. Then in a modest tone he said, "I am not

sure what it will add to what we already know. Anyway, London is full of ex-ambassadors."

While stands the Coliseum, Rome shall stand;

When falls the Coliseum, Rome shall fall;

And when Rome falls- the World.

- Lord Byron

Post-script: My first meeting with Parviz C. Radji took place on Wednesday, 13th

March 2002 in London.

|

|

|