Imbaba

No wonder Egyptians loved Iranians so much

Written & photographed by Dokhi Fassihian

February 11, 2000

The Iranian

I was studying Arabic in Cairo during the summer of 1997. Living among Egyptians

was an extraordinary experience. They welcomed me as their own and would never believe

it when I told them I wasn't Egyptian. When they found out I was Iranian, they treated

me like a queen. Egyptians mean it when they tarof; their friendliness and warmth

is full of sincerity: I got the best tables at restaurants; gifts at the bazaar,

free feluka rides on the Nile, free taxi rides.

"We haven't seen Iranians for ten years," a bazaar merchant told me.

"Only Farah Diba and her entourage come to visit the Shah's tomb every year,

and they usually just visit the jewelery stores."

A man working in a baghali, or small supermarket, once said to me, "I love

[then Iranian Foreign Minister] Velayati! We Egyptians love Iranians. We have deep

respect for your culture and your politics. Will you take me to Iran?"

One of the most memorable times in Cairo was my visit to the slums; a place called

Imbaba. It was a different world, one far removed from anything I had ever seen.

But going there was no easy affair. Every time I would ask someone to take me, they

would refuse. "Why do you want to go there?" "It's not a good idea."

"You can't go and just watch people."

That summer, I met a wonderful young Egyptian man named Ashraf. He was serving

his compulsory two years in the military and was required to spend the majority of

the week at the barracks outside the city. Getting time off was close to impossible;

he came up with every and any excuse.

I only had a few weeks left in Egypt so Ashraf arranged to take time off through

a personal favor. His commanding officer asked him for a simple favor -- to drive

to his house in Imbaba, pick him up, drive back to Cairo to pick up his television

set which was being repaired, and then to drive back to Imbaba. In return, Ashraf

could have the weekend off.

"I want to go," I said to Ashraf. "Impossibe," he replied

in his perfect English with a slight British/Egyptian accent. So, I begged. "I've

been in Egypt for two and a half months and I still haven't seen the slums. This

can't be what all of Cairo is like--please."

I lived in Zamalek, a small island on the Nile which was a relatively rich area

and where many foreigners stayed. I was desperate to see more and being a single

Middle Eastern woman really infringed on my mobility. I had to find a way to use

it to my advantage.

"What would I say?" Ashraf asked. "It would be disrespectful for

me to bring a girl with me to see my commanding officer, this is not the U.S., besides,

I'm going to a very poor and traditional neighborhood, there would be too much attention."

I didn't let up. "Please, see, I've thought about it. I'll act like I'm your

long lost cousin from the States. Everybody thinks I'm Egyptian anyways."

After much discussion, he agreed. I promised to dress very modestly, to sit in

the backseat when we picked up the general, and make no mistakes regarding our family

background.

Imbaba was about an hour away. We drove through the choking

pollution, through deserted dry plots of land littered with all sorts of trash. Kids

played soccer barefoot among the labrynth of hard dirt and garbage. Factories bellowed

huge amounts of black smoke into the air.

Imbaba was about an hour away. We drove through the choking

pollution, through deserted dry plots of land littered with all sorts of trash. Kids

played soccer barefoot among the labrynth of hard dirt and garbage. Factories bellowed

huge amounts of black smoke into the air.

"These are the gifts Nasser left for us," Ashraf said in a tone full

of resentment. "He built factories near the city to keep workers close by in

case he needed to mobilize them for political support."

As we drove further and further toward Imbaba, the stench of poverty overwhelemed

my senses. The farther we drove, the more dreadful our surroundings became. All I

could see for miles were piles and piles of trash everywhere and, here and there,

children playing among them. I couldn't help but stare. People stared back at me.

Tears welled up in my eyes. "What was the point of coming? I knew you would

just get depressed," Ashraf said gently.

I had never seen anything like it. How was it possible

for people to live like this, I thought. The dejection was unbearable. The area was

completely neglected by government authorities, to the point that Imbaba must not

have even existed in urban plans or received any municipal services.

I had never seen anything like it. How was it possible

for people to live like this, I thought. The dejection was unbearable. The area was

completely neglected by government authorities, to the point that Imbaba must not

have even existed in urban plans or received any municipal services.

We pulled into what looked like a narrow unpaved road. Pedestrians cleared the

road and touched the car as it passed. It took me a while to realize we had entered

a neighborhood with homes. Ashraf stopped the car. "Where are we?" I asked.

"His house is right there, stay here, I'll go get him."

I looked around. The place did not look livable. It was strewn with all sorts

of litter, I couldn't make out any clear living spaces, there were a few holes in

a huge wall, the rest was dirt and trash. The apartments were makeshift mud and brick

structures. I couldn't stay in the car.

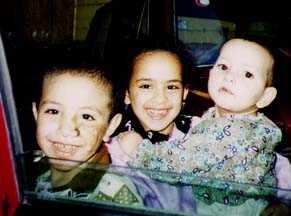

I was the only woman in the alleyway not wearing the hejab. I walked around and

saw what looked like a young brother and sister fighting. I smiled and began speaking

to them in my broken Arabic. They didn't understand my classical Arabic; their dialect

was incomprehensible to me. They touchd me and giggled.

The little boy wanted to get inside the car so I let

him sit in the driver's seat and act like he was driving. He rubbed his hands around

the steering wheel and made honking noises. The little girl came back holding her

baby brother in her arms. She just smiled. There were scars from a fast spreading

skin disease on their beautiful faces and hands.

The little boy wanted to get inside the car so I let

him sit in the driver's seat and act like he was driving. He rubbed his hands around

the steering wheel and made honking noises. The little girl came back holding her

baby brother in her arms. She just smiled. There were scars from a fast spreading

skin disease on their beautiful faces and hands.

Then I noticed the ground was moving beneath me. A closer look revealed millions

of flies, flies as far as my eyes could see, swarming on the ground. Horrified, I

got back in the car.

Ashraf and the general walked toward the car. He was a handsome heavy-set man

in his thirties, and very friendly. Ashraf introduced me in Arabic as his second

cousin who grew up in the States. Ashraf and I looked nothing alike! He was light-skinned

with dirty blond hair and gray/green eyes and I, a dark-eyed olive-skinned Persian

girl. But the general never doubted our story.

We drove on the dirt road back to the main road toward Cairo's sprawling main

downtown. I apologized to the general for not being able to speak Arabic well. He

was disturbed and lectured me through Ashraf about the importance of maintaining

my native culture. "Don't her parents speak to her in Arabic, I am very surprised,

Egyptians usually don't lose their culture?" I expressed my regret and promised

to practice my Arabic.

The rest of the time the general complained to Ashraf about his personal problems

in an effort to gain future favors.

When we dropped off the general with his fixed TV set, he bought Ashraf and I

orange sodas from the local canteen. He was ever so gracious and sincere as we said

our goodbyes. Driving back to Cairo and sipping our sodas, I asked Ashraf, "How

is it that he is a general in the Egyptian army and he lives in such awful conditions?"

I reflected on Imbaba's history -- it was the stronghold of the Muslim Brotherhood

or Game'ah Islamiyya, and at one point the self-declared Republic of Imbaba. This

was the breeding ground of the Islamic movements which spread through the Middle

East in the 70s and 80s.

It was a huge dichotomy. Government authorities feared Iranians, ordinary Egyptians

adored them. Even with an American passport, I was detained in a small room for five

hours in the middle of the night upon my arrival in Cairo. The cruel interrogators

drank small glasses of tea and smoked cigarettes until I joined in on their little

party and tired them of their power trip. Why? Because I was born in Mashhad.

To ordinary Egyptians, Iranians had achieved what they had envisioned, and what

many of them still longed for. It wasn't necessarily Islam -- they saw independence

and dignity in the Iranian revolution. They had no idea that the standard of living

in Iran had halved since the revolution and young Iranians desperately yearned to

leave their country.

Twenty years after the revolution, beggars on Vali Asr in northern Tehran reminded

me of beggars in Cairo. Once I saw a tiny Iranian boy who couldn't have been older

than four years-old, begging for money.

"What is your name, where are your parents?" I asked. "They're

at home," he replied without hesitation. "Why are they at home, why are

you here asking for money? Will you take me to them?" I asked. "No, they

told me to come here and ask for money." "Why doesn't your father come

and ask for money?" The little boy replied, "No, he can't, he's a grown

man, and grown men don't beg."

So, there was room to debate the dignity of the Iranian revolution.

Mubarak's Egypt reminded me of the Shah's Iran. Income disparity was huge. Across

the river on the west bank, Imbaba was laced with refuse, rodents, and trash. It

was a place where children, donkeys, and sheep drank from open sewers at night. During

that trip, I read about a funeral for two children eaten alive by rats. Its population

density was 105,000 people per 2.2 square miles; an average of 3.7 people lived in

every room. On our side of the Nile, the level of literacy was among the highest

in the world; in Imbaba, the average income was thirty dollars a month and residents

could only afford to buy camel meat.

Political Islam wasn't such a mystery after all. It arose from abject poverty

and despair. No wonder Egyptians loved Iranians so much.

![]()