High spirits

Shiraz wine: from Persia to Australia

By Cyrus Kadivar

February 8, 2000

The Iranian

What drunkenness is this that brings me hope -

Who was the Cup-bearer, and whence the wine?

- Hafez

One ancient Persian legend says that Jamshid, a grape-loving king, stored

ripe grapes in a cellar so he could enjoy grapes all year long.

One day he sent his slaves to fetch him some grapes. When they did not

return he decided to go to the cellar himself only to find that they had

been knocked out by the carbon dioxide gas emanating from some bruised

fermenting grapes. One of the king's rejected, distraught mistresses decided

to drink this poisoned potion, only to leave the cellar singing and dancing

in high spirits.

The king realised that this fruity liquid had the wonderful and mysterious

power to make sad people happy. When Alexander overthrew the powerful Persian

empire he entered Darius's palace in January 330 AD. During one of the

conqueror's orgies soldiers raided the wine cellars. In a drunken moment

Alexander ordered the destruction of Persepolis.

Shiraz, lying 5,000 feet above sea level, yet only 100 miles from the

sea, had the essential combination of factors necessary to a successful

vineyards. To the Persians, paradise was called Khollar - a village in

the mountains beside Shiraz. The region supplied Baghdad with wine under

the caliphs. In the 12th and 13th century Persian poets such as Hafez extolled

the beautiful maidens, roses and wine of Shiraz.

According to Jean Chardin, a young French jeweller who spent most of

his time in 17th century Persia, the wine of Shiraz was famous in Europe

and many members of the European trading companies imported it under contract

from governors with royal authorization. Shiraz had its own bottle-making

industry and wine was transported in large jars in baskets over long distances.

Chardin gives a fairly full account of the wine trade in A Journey

to Persia. "This wine which is so excellent and famous, is

called Shiraz, and for the beauty of its colour and the delight of its

taste is considered to be the best in Persia and throughout the East. It

is not one of those strong wines which pleases the palate straight away."

The Shiraz grape was probably the root of the Syrah grape often found

in hot places like the Rhone Valley in France. The wine business was still

in full swing in the 19th century when a British doctor with the telegraph

company, C.J. Wills, wrote how his friend and neighbor in Shiraz , the

Mullah Haji Ali Akbar, approached him with the proposition that they should

make wine together in Dr Wills' house.

"I cannot make wine in my house," said the Mullah. "I

am a Mohammedan priest. But if I ask the Jews to make it for me things

will be even worse, because the wine will be dreadful, and I am a connoisseur.

If I make it at your house, Sahib, it will be first class and I will kill

two birds with one stone. You and I will have good wine and there will

be no scandal about it."

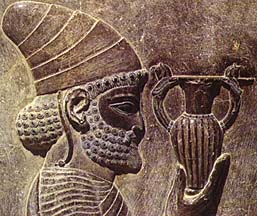

In the 1920s European archaeologists digging in the ruins outside Shiraz

discovered immaculate drinking cups of gold shaped as fierce lions and

winged ibex. Local wine production was encouraged under the Pahlavis. On

the eve of the revolution there were plans to export Shiraz wine with French

assistance. In 1979 many wine bottles were smashed by Islamic fanatics.

A few Shirazis continued to make their own homemade wine despite the threat

of being publicly flogged if caught by the vice police.

These days Shiraz wine is not Persian but rather a produce of Australian

and South African vineyards. Still, many Iranian restaurants in London

will insist that what the customer is drinking is the real thing. It is

a myth that seems to bring a smile to many in exile.

![]()