|

|

October 14, 2002 I It was a day perfectly set against the background of tranquil, moral Switzerland -- the perfect place to plan a war... First, he bought himself $1.1-billion worth of nuclear reactors from France; not for the plutonium, but for the energy, he said, which seemed a bit peculiar to some observers at the time, since if there was anything that Iran definitely did not need -- holding, as it did,the fourth-largest known oil reserves in the world -- it was more energy. Then, in a great act of generosity, he lent Britain $2 billion to keep that island afloat financially, and promised that more would be available if the need arose.And, under the leadership of Harold Wilson, of course that need arose. With the result that Her Majesty's government in London suddenly found itself in hock to His Majesty's government in Teheran. England, the protector of the peace in the Middle East for two centuries, now suddenly found itself a client state of Iran. Then the shahanshah bought 25 per cent of that grand old company of the Ruhr, Fried Krupp Hflttenwerk. It was only a matter of time before he took over complete control. Old Hitler buffs thought they had spotted a trend developing, but nobody paid attention to them, even when the shah, in a further act of generosity, offered to bail out a little company in the United States that made the type of toys that Reza Pahlavi liked to play with warplanes. It seemed that, next to the Pentagon, the shah was Grumman's largest customer. It further seemed that he was very worried about getting delivery of 80-odd F-l4 interceptors on time from Grumman. Because he needed them for the War of 1976. As it turned out, he got them right on schedule, plus 70 more Phantoms from McDonnell Douglas, a number of which were equipped with nuclear bomb racks. Now he was in a position to make the Persian Gulf an Iranian lake, and have the entire world at his mercy thereafter. But first he had to convince his big brother to the north, the Soviet Union, that all this was a great idea -- and also attend to a few other details. That's why he went to Switzerland. On February 13, 1976, the shah of Iran arrived quietly in Zurich. As usual, he moved into the Dolder Grand Hotel; it was close to the clinic where he had his annual medical checkup. His entourage was not large: his young wife, Farah Diba, their children, her lady-in-waiting, his aide-de-camp, and about twenty security men. Few people took notice of them. It was, after all, the shah's twelfth consecutive winter visit to Switzerland. On February 18, apparently in good health, he and his family left by private jet for St. Moritz. Just before takeoff, two men, who had arrived at Kloten airport from Teheran just an hour earlier, joined the flight. The shah was at the controls of the jet most of the way, but turned the plane over to the Swiss pilot before landing. The shah knew the small airport at Samedan: it was squeezed between the mountains behind Pontresina to the south and those of St. Moritz to the north, and averaged 1.6 fatal crashes a year. Most of the security men had gone on ahead the day before in three Mercedes 600's. All three were on the tarmac when the Lear's engines were turned off. About twenty minutes later, the shah's party moved through the gates leading onto the grounds of the Suvretta House on the eastern outskirts of St. Moritz. In this city, the nouveaux riches stayed at the Palace; those who inherited wealth or title, or succeeded to both through marriage, stayed at the Suvretta. The shah, while still married to Soraya in the 1950's, had learned to love skiing in the Swiss Alps, and also to appreciate the setting of this particular Swiss hotel with its pine forests and the towering Piz Nair beyond. But he especially enjoyed the solitude, beyond the rude stares of German tourists with knapsacks full of leberwurst sandwiches and sauergurken. In 1968 or 1969, the shah had purchased a villa on the grounds of the Suvretta. It made things easier for the security men, and it added a further dimension of privacy. Yet it did not involve sacrificing the superb service and cuisine offered by one of Europe's finest hostelries. The manager of the Suvretta, Herr R. F. Mueller, flanked by two assistants standing well to his rear, was waiting outside the main entrance to the hotel. The welcome was brief. The window at the back of the first Mercedes was open not more than one minute while the pleasantries were exchanged. Then theconvoy of three limousines moved on. Both the windows and the curtains on the windows at the rear of the second limo remained closed. The third car was wide open, much to the discomfort of the shah's six bodyguards inside, who were not used to the air of the Engadin Valley in February, which hovered around the freezing level even at noon. The shah and his family had a brief lunch, and by 1:30 were out on the small practice slope, about 75 meters from the villa. Herr Mueller had discreetly arranged that they have exclusive use of the tow lift for the afternoon. Two veteran ski guides were there to assist. A good dozen security men, half on skis, posted themselves along the slope. The children, of course, protested the need for spending any warm-up time on what the Swiss term an "idiot hill"; they preferred to move right up to the main slopes of the Piz Nair. But papa remained firm. At 3:30, as the temperature began to dip radically and patches of ice started to appear, everyone returned to the lodge. They all had cheese fondue that evening. Thus ended a typical day in the life of His Imperial Majesty, the shahanshah of Iran -- devoted husband, dutiful father, sportsman. A day perfectly set against the background of tranquil, neutral, clean, moral Switzerland. It was, in fact, the perfect place to plan a war. Which was exactly what the two men who had remained so secluded in the back seat of the second limousine had been doing in the south wing of the shah's villa, while the Pahlavi family cavorted in the snow. They were General Mohammed Khatami, head of Iran's air force, and Commander Fereydoun Shahandeh, the Iranian air-sea strike chief for the western part of the Persian Gulf. As military men are prone to do, one of their first acts upon settling into their St. Moritz billet had been to pin a huge map to the wall. Its dimensions were illuminating, stretching from India in the east to the Mediterranean in the West; from the southern perimeters of Russia to the north to as far south as Yemen and the Sudan. Both the general and the commander had the appearance of happy men. And why not? They controlled the biggest and best-trained army in the Middle East; the largest and most sophisticated air force; a flexible, modern navy. In addition, Iran possessed the world's most extensive operational military Hovercraft fleet (British-built SR.N-6's and BH.7's), and an awesome arsenal of missiles, ranging from the U.S.-built Hawks to the British Rapier to the French Crotale, but its most dangerous weapon was, of course, the American Phoenix stand-off missile guided smart bomb.

Downhill all the way: To man all this equipment, Iran had an army of 460,000 men (including reserves)

, reputed o be the most efficient fighting force in the Middle East (with the exception

of Israel), thanks in part to the training provided by over 1,000 American military

personnel who were sent to Iran in the early 1970's for that purpose. (The total

military hardware that was at Iran's disposal is shown in the inventory list

on this page.) All the Iranians lacked was a nuclear capability. And they would even

have that, provided the shah pulled off his final deal in St. Moritz. The penultimate

one had to be with the Russians. That was scheduled for the following day. The Russians knew that the huge truck plant which Fiat built in Togliattigrad in the early 1970's was also eminently suitable for manufacturing such items as tanks, armored personnel carriers, even aircraft frames in a pinch. It required only a conversion job costing around a billion dollars, and a contractor that had the know-how and the spare engineering capacity. Fiat had both, thanks to the fact that for decades it had been one of the major suppliers of arms to NATO, and the further fact that as a result of Italy's disastrous economic situation, half of Fiat's capacity lay idle. So Fiat had tendered a bid that at best would cover its overhead. The Russians knew this, and Grechko had been fully prepared to sign the deal the very first day in Turin. But Russians never sign anything the first day. So the five-day visit. This Thursday had been scheduled as Grechko's day off, a day to be spent privately. enjoying the unique beauty the Alps in winter. The Fiat entered the grounds of the Suvretta House. and headed directly for the shah's villa. The two Russians had barely emerged from the car when General Khatami and Commander Fereydoun Shahandeh appeared. Four handshakes, a dozen words, and they disappeared inside. The shah was standing in front of the fireplace in the library when they entered. He extended a hand to each Russian, and indicated that they would be seated on the sofa behind a massive wooden coffee table. He himself chose an armchair on the opposite side. The two Iranian military men remained standing to the shah's rear. "We shall speak English," were his first words. Marshal Grechko nodded his agreement, so the shahanshah continued. "I do appreciate your agreeing to this rather unusual arrangement. You understand that it would have been impossible for me to come to Moscow, and very awkward to receive you in Teheran." "We fully understand, Your Majesty," replied Grechko through his interpreter and both nodded their heads slightly as the words were beingrepeated. Russians are as much in awe of royalty as are Americans. "The subject I wish to discuss is Iraq. It is not the first time that that country has come up in our talks over the years." Silence from the sofa. "You are, of course, aware that Iraq has attacked Iran at least a dozen times during the past five years. It is preparing to attack again, this time on a massive scale," Still silence. "We further believe that the Americans will use this military conflict as excuse for intervention, in order -- as they so nicely put it'to 'stabilize' the Middle East." "How?" asked Grechko through his translator. "There are 12,000 American military 'advisers' in Saudi Arabia. For yearsthey have been trying to convince Faisal that Iran, not the United States, is the real enemy of the Arab people. And what better proof than a major Iranian-Iraqi armed conflict? Now to answer your question: the Saudi/American armed forces would move immediately to 'secure their northern flank.' Which means their occupation of the entire western coast of the Persian Gulf, up to and including Kuwait. But, all this can be prevented." "How?" repeated Grechko. "Very simply, though at great sacrifice to my country. Iran would make a preemptive strike. Not just against Iraq. We would simultaneously neutralize Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, as well as the northern tip of Oman. We will have the entire Persian Gulf -- both sides -- in our hands before the Americans even find out. After that they, and their friends the Saudis, will be finished in the Middle East." The shah paused, and then added six further words: "Provided your country does not intervene." "We could not stand idly by," said Grechko immediately. "Iraq is our friend." "But so is Iran. And it is I, only I, who can stop the Americans from gaining control of the Gulf." "There are other reasons," continued the shahanshah. "For example, would it be in your interest if we were forced to suspend shipments of natural gas to your country, especially now that the second pipeline is in operation? "Why should you have to do that? We have very firm agreements!" Grechko was getting angry. "Because," replied the shah, calmly "if we allow Iraq to attack, its first target on Iranian soil will be Abadan.The refinery complex there is the largest in the world, and Iran's prime source of energy. It's within artillery range of Iraq. But our gas fields are beyond Iraq's reach. I think it should be obvious that after Abadan is destroyed, we will have to immediately stop all exports of gas. We will desperately require every cubic foot for domestic consumption." The shah raised both hands in a gesture of impatience. "But why should I dwell on circumstances which need not ever develop? With the agreement of your government, I can prevent such a catastrophe. Then not only will you have your gas but much more. I will be prepared to enter into a five-year agreement on shipments of crude oil to the Soviet Union -- at a fixed price. Ten dollars a barrel. Up to half a billion barrels a year." "It is too dangerous," said Grechko. "I am also in a position to lend you an F-l4. Or two, if you need them." Now Grechko's eyes flickered. The American F-14 was the only aircraft superior to the MiG-25, and both planes were planned as the top-performance interceptors of their respective countries in the 1980's. That Grechko understood. Let the people back in the Kremlin calculate the gas and oil thing. "How soon do you need an answer?" "Within three days." "And if it is negative?" "Then you had better find your own way of coping with the Americans." The shahanshah rose. The audience was over. But Grechko, though also rising, persisted. "How do you know the Iraqis are about to attack?" The shah's hand motioned to General Khatami. Out of his briefcase came two aerial photographs, compliments of a camera built by Kodak, as mounted in an aircraft built by McDonnell Douglas -- a total package for which the shah had paid $15 million in 1974. "This," said Khatami, taking the first photograph and pointing at the river forming the border between Iraq and Iran where the two countries meet at the northern tip of the Persian Gulf, "is the Shatt al-Arab River. Note the incredible concentration of artillery displacements and missile launching sites here, opposite Abadan, and there, vis-à-vis Khorramshahr." Khatami presented his second photo. "Now this is the territory immediately to the north -- the narrow plain between the Tigris and the Iranian border. You can quite clearly see the armor. Here, ready to move on Ahvaz. There, poised at Dezful. The idea, obviously, is to sweep cast and then south to secure Abadan and its surrounding oil fields." [...] put the photographs aside. "All in all we have counted about 1 ,700 tanks in that corridor east of the Tigris -- 800 1-55's, 450 M-60's, and around 500 BTR-152's. They represent 90 percent of the total tank force Iraq possesses. This type of concentration has never occurred before. At least half of the Iraqi forces have always been kept in the north, to contain and destroy the Kurds. Furthermore, the entire Iraqi Air Force has been on alert since last Wednesday. The army reserves were recalled last Monday. All this is, of course, quite easy for you to verify." The marshal spoke: "I shall be leaving Italy for Moscow tomorrow afternoon. You will hear from us immediately thereafter." Grechko bowed, turned, and left. Minutes later the shah walked out of the chalet with his wife and children. It was a perfect day for skiing. II In addition to the aircraft, the package Dassault hoped to sell included 1,500 Matra R.530 missiles (some with radar, and others with infrared homing heads), as well as 500 of the new French laser-guided stand-off weapon (its characteristics being very similar to the American Phoenix), which tested out with a better than 95 per cent hit rate even on targets as small as single armored vehicles, or parked aircraft. If accepted, this deal would have major long-term consequences for France. It, not the United States or Russia, would become the chief supplier of arms to the biggest single customer for weapons that had ever existed -- the shahanshah. The French asking price for this initial package was $5.1 billion. They proposed

that 50 per cent be paid on signing, the other half on delivery. The shah, in the

preliminary discussion earlier that year, had indicated he would prefer another mode

of payment. For the shah was very cash-flow-conscious (his cash was earning him 15

per cent per annum at Chase Manhattan in London). He preferred to pay in kind. And

kind, in Iran. means crude Oil. Were there any possible circumstances under which the French bombs might be used?

Of course not! You could not fight and win a nuclear war with only six bombs! He

needed them only to be able to honestly counter a probable Iraqi-Soviet nuclear bluff.

If he could not, the chances were very high indeed that Iran would become yet another

satellite within the Soviet orbit. Such was obviously not in France's interest, especially

now when Iran was about to develop into France's largest single export market on

the one hand, while guaranteeing France's future petroleum supply on the other. N'est-ce

pas?

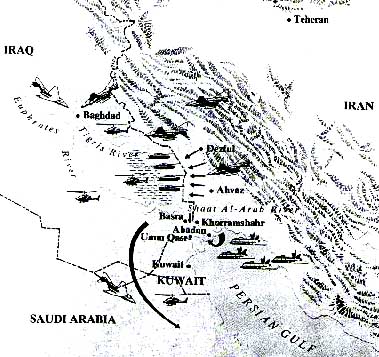

Iranians on the way to Conquest III Two days to rebuild an Empire Iran defeats Iraq and sweeps the Persian Gulf in a blitzkrieg that starts with air strikes on Iraqi airfields and bases. These are followed by Hovercraft encirclement of Iraqi tanks that face Iranian armor between the cities of Dez Jul and Ahvaz. The victorious Iranians then move down the Arabian coast, capturing Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Dubai, and Oman. The inset map shows the extent of the ancient Sassanid Empire -- Persia's period of greatest expansion, and inspiration of the present shah.

The king of kings was 56, and before he died he intended that the glory of ancient Persia be restored. See larger map His first move was right out of the Israeli book: 100 Phantoms, equipped with

their Phoenix stand-off missiles, made low-level dawn raids on all eight major Iraqi

military bases. Iraq at this time had 30 MiG-23's, 90 MiG-2 l's, 30 MiG-17's, and

36 dId British-made Hunters. All but 33 of these aircraft were destroyed on the ground

before the sun was up, thanks to the remarkable accuracy of the Phoenixes and to

the skill of the Iranian pilots, all of whom had been schooled by the United States

Air Force. The idea was tailor-made for the geography of the area. Remember all those Iraqi tanks in the corridor between the Tigris River and the Iranian border? Well, behind them -- to the west -- were the swamps of the Tigris-Euphrates delta, impassable terrain from the military standpoint. Impassable, that is, for every military vehicle known to man except the Hovercraft, which could move on top of its air cushion across anything that was reasonably flat -- water, swamp, or beach -- and at a speed of 40 mph., fully loaded. These remarkable machines (all built for the shah in Britain, the world's leader in Hovercraft technology) could move an entire armored battalion: in their cavernous bowels were tanks (Chieftains, also British-built) and armored personnel carriers (BTR-50's and BTR-60's,of Soviet origin) plus a full complement of military personnel in the wings and on the upper decks. They had a range of 150 miles. But they could not move until the naval base at Umm Qasr had been put out of action, and until the Iraqi fire power on the west bank of the Shatt al-Arab -- the gateway to the Tigris -- Euphrates delta -- had been eliminated. By 9 AM, it was. Immediately, the beaches on the Persian Gulf to the east of Abadan were filled with the howl of Hovercraft engines, as the air pressure was raised within the skirts beneath the vehicles. By 9:15 all 45 craft were under way. As these grotesque weapons of war moved around the corner, and up the Shatt al-Arab channel, the scene resembled a Martian invasion. Only two hours later, they began opening up their ramps on firm ground to the rear of the Iraqi forces. At the same time the main body of Iranian panzers, which had been grouped between Dezful and Ahvaz, began a frontal assault from the east. It was nothing less than a massacre. Already by early afternoon the vast majority of the Iraqi forces chose surrender. IV Meanwhile, back in Washington, Secretary of Defense Schlesinger and his chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Brown, were having drinks at a cocktail party, in Chevy Chase, being thrown by Senator Stennis of Mississippi in honor of himself. The first hint that something was going on started coming in around 8 P.M. Eastern Standard Time, on this 29th of February. The word caime from the Aramco communications center in Riyadh, was sent to the Standard Oil people in New York, and then relayed to the Pentagon. Since it was a weekend, they sat on it there for a while, and then some colonel decided that he'd better cover his back just in case. So Schlesinger was alerted by telephone out at Chevy Chase. "Goddamned Iraqis," was Schlesinger's comment to Brown after hanging up, "they've attacked Iran again. But this time in real style, apparently." Brown did not trust either the defense secretary or Standard Oil, so he immediately arranged for an aerial reconnaissance sweep of the region. Schlesinger thought he'd better call Henry. Nancy answered the phone and said Henry was at the office. So Schlesinger called the State Department. "You have a problem, James?" was pronounced "Chames." "Yes. Henry. Apparently Iraq has attacked Iran. And this time the shah's shooting back." "We have nothing on this at State" "It does not surprise me." Henry did not think that descry comment. "When will you have more," Kissinger asked. "Within the hour." At the end of that hour, Schlesinger and Brown were on their way to the White House. Henry, William Simon, and Nelson Rockefeller were in the Oval Office with the president when they arrived. All were drinking bourbon and branch water, so Schlesinger and Brown also drank bourbon. Mr. Ford asked the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to brief the group. Brown told of the air strikes around Baghdad, of the destruction of the Soviet-built naval base at Umm Qasr, and of the Shatt al-Arab end run. He did not consider these developments unfavorable for the United States. Quite the contrary. Iraq was a client state of the Soviet Union's. Iran was a client state of the Pentagon's. What was good for the shah was therefore good for America. The Hovercraft end-run: Iranian troops debouch front the swamps of the Tigris-Euphrates delta onto firm ground, having crossed the nearly impassable terrain by means of Hovercrat -- British-made vehicles that speed along on a self-generated air cushion. At this point the Iranians are poised to attack the main concentration of Iraqi tanks front the rear, taking them completely by surprise and forcing surrender. Triple strike: The war begins with airborne missile attacks that devastate Iraq's military bases. Iraq's Russian-built naval base at Umm Qasr is seen here under attack by Iranian troops brought in by helicopters.

Command indecision: Confronted by confused reports of hostilities between Iran and Iraq, President Ford meets with the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Stall, General Brown (far left), Vice-President Rockefeller, Henry Kissinger, and Defense Secretary Schlesinger. James Schlesinger endorsed this statement "without any reservations whatsoever."

It was totally consistent with American policy as initiated by Johnson in 1968, and

continued by the Nixon and Ford administrations ever since. V "Our Iranian friend called just to pass along a little message from the shah. He wants to assure us that he remains a staunch friend of the United States, and can now insure stability in the Middle East, an objective which, he says, our two nations have been jointly pursuing during the past decade. He added a P.S.," continued Kissinger. "He wants to calm any fears we might have concerning a possible attempt by the Soviet Union to take advantage of the situation by trying to move into the area through nuclear blackmail. Fortunately Iran possesses a quite adequate nuclear capability, thanks to the help of his two best friends: the French, who helped him get the bombs, and America, which has provided him such efficient delivery systems. He sends his best regards to you. Mr. President."

"What do you think, Henry?" asked Ford. "I don't know him well enough. But I do know somebody who does." "Who?" "Bill Rogers. Right after he resigned as secretary of state, he went to work for the Pahlavi Foundation." "Call him." So Henry did. Rogers's answer was slow to come, prudently worded, but quite clear: the shah probably had nuclear weapons, and if he was threatened by B-52's and the Sixth Fleet, he'd use them as a last resort. There was a carefully couched suggestion that an element of irrationality in the shah's character should not be ignored. When Henry had finished, somebody muttered: "We should have given that bastard the Allende treatment years ago." But nobody heard it. Three hours later a message was on the way to the shahanshah of Iran from the president of the United States. It expressed the hope that Iran and America would work as partners toward peace in the Middle East in the future, as they had in the past.

That did it. Within two months Italy and Britain were bankrupt. The dollar

had collapsed, along with a few thousand banks. Wall Street lay in ruins. And these

were only the first doinirtoes to fall. The Crash of '76 was inevitably followed

by the Revolution of 1977. the Famine of 1978, the Collapse of Society in 1979 ...

and ultimately, the End of the Industrial Era. Today, in 1984, most survivors say

that it has all been for the good. At least the ones here in California who don't

have to worry about starving or freezing to death. I'm not sure. Sometimes I like

to stop and think back on the old world -- but, right now, the cows need milking.

|

|

Web design by Bcubed

Internet server Global Publishing Group

Making history

Making history