Will anyone miss us? Will anyone miss us?

Accompanying the Shah on a visit to communist Russia

By Farhad Sepahbody

April 25, 2003

The Iranian

Someone once said that writing and expressing can

heal. It can focus, support, and enhance our lives and well being.

Whether we laugh or we cry, whether through sorrow or joy, we can

understand more about ourselves, and each other, through writing.

The official or business part of a state visit was

invariably grueling, tiring. As a diplomat, I had to take notes,

attend all meetings, write down all that was said, prepare statements

and reports, decipher and send cables; sit down at long lunches,

dinners, and a lengthy list of other chores that kept me awake most

of the night. But when work was over, things got better and visiting

new places was rewarding.

So let me write about the instances that were fun

and joyful. Here it goes... an Iranian visit to Siberia where no

foreign head of state had ever seen.

Lake Baikal, Siberia, Summer 1966

It is a very hot July day and we are about to land at Irkutsk airport.

There are rows upon rows of white passenger jet planes shining in

the sun, parked all over the airport. I have never seen so many

jets assembled in one airport, not even at New York's JFK. From

the window of our plane it all looks very impressive. Maybe the

Soviets flew them specially there in order to display their

might to the Shahanshah of Iran.

Still, I am wondering why the Russians did not provide

the King with one of the latest jewels in their fleet. The trip

would have taken much less time instead of the agonizing, tedious

ten-hour flight from Moscow. But then I read somewhere that the

new jets were still plagued with a few bugs. Our Tupolev turboprop

jet, however, was a safe, reliable workhorse.

Baikal's all electric train

The airport is decorated with Persian and Soviet flags.

There are welcoming banners in Persian and Russian everywhere. The

Queen is dressed in a simple dress she wore the previous year on

our state visit to Brazil. She is is surrounded by young girls and

boy scouts. They belong to communist youth organizations and are

smartly dressed in white and red. The smiling Queen receives a bouquet

of flowers.

Following the habitual "warm welcome", the

Shah stands at attention on the dais while our national anthem,

the enticing Salam

Shahanshahi is played, followed by the Soviet

Union's hymn.

After a review of the troops and short speeches

we proceed by train to lake Baikal. The King is interested in just

about everything he sees and asks quantities of questions while

relaxing in the superbly equipped and spotless coach of the electric

train zooming us to Baikal.

It could have been like this in the dead of winter

A pretty Intourist girl, hands out pamphlets of the region and explains:

"The region of lake Baikal, the "Blue Eye of Siberia",

is among the most beautiful areas of Russia. Lenin was here during

part of his long exile. While in Moscow, I visited Lenin's Mausoleum

where he was lying in glass coffin, ashen and glassy. It gave me

shock.

Rather undiplomatically Tania adds that the "tyrant

Tsar" banished Lenin. Then she supplies me with one of his

poems dedicated to the lake. She adds: "It is home to more

than 2,500 plant and animal species, many of which are found nowhere

else. We will explore the 300-year-old city of Irkutsk and take

a ferry to Olkhon Island, part of the Pribaikalski National Park

and home to Baikal seals. We will also visit a giant new dam. We

Russians, love trekking in the eastern Sayan Mountains along the

western coast of the lake. There are extensive fir forests and the

Taiga. It is full of wild animals."

Lake Baikal, she goes on, is located in the south

of Eastern Siberia, in the Buryat Autonomous Republic and Irkutsk

Region of Russia. It covers 31,500 sq. km. and is 636 km. long,

on average 48 km.wide, 79,4 km. at its widest point. Its water basin

occupies about 557,000 sq . km. and contains about one fifth of

the world's reserves of fresh surface-water and over 80 percent

of the Soviet Union's fresh water. Baikal is the deepest lake in

the world. Its average depth is 730 meters and maximum depth in

the middle, 1,637 meters.

The Locomotive

I proceed to film from the window of the coach with my small 8mm

Canon camera, a gift from my sister Parvine, who was stationed with

her diplomat husband in Japan. Queen Farah Pahlavi on the other

hand had a splendid 16mm camera, with sound to boot. (Unfortunately

my film footage of various occasions disappeared at the outset of

the Iranian Revolution when our house was plundered. I hope someone

is still enjoying them.)

The tall pine trees, firs and little isbas

(sort of Russian chalet) are bewitching. The train slows down, coming

to a stop at a small station and lo and behold a beautiful black

locomotive of yesteryears with red markings and so many wheels I

can't count, stands majestically on the tracks, steaming and puffing.

It looks like a living, screaming monster. The tall pine trees, firs and little isbas

(sort of Russian chalet) are bewitching. The train slows down, coming

to a stop at a small station and lo and behold a beautiful black

locomotive of yesteryears with red markings and so many wheels I

can't count, stands majestically on the tracks, steaming and puffing.

It looks like a living, screaming monster.

I notice the German markings of Krupp on the shiny

steel. Probably a spoil from World War II. When we get off at this

final stop, I cannot resist filming the locomotive, it seemed alive.

A heavy pat on my shoulder makes me jump. Someone from the station

disagrees vehemently to my filming and there is a commotion. Russians

are sensitive especially where railroad stations are concerned.

Fortunately this infringement to rules and regulations,

bordering so it seems on spying, is quickly forgiven. An official

from Moscow tells the finicky and now dismayed railroad employee

that I am allowed to film whatever I want. "Kharacho,"

everything is OK.

The Shah who noticed the incident, has a faint smile

on his lips. This little faux-pas it seems, rather amused His Majesty

and I did not gather the Imperial wrath. At the outset of the long

expedition he had stressed to us: "If you want something, like

bananas for example, just mention it aloud in your room. Generally

there are microphones hidden in the walls and the next day, if not

sooner, your wishes are granted. I experienced it myself, on my

first visit to Russia, I felt like having a banana and wished for

it aloud. There was no one in my room, but the next morning a banana

was on the table."

Later on, in the seventies, I tried this trick while

on an official visit with the Shah and Foreign Minister Ardeshir

Zahedi to America. We were staying at Blair House opposite the White

House. Instead of ham and eggs, I wished for caviar at breakfast.

Nothing happened. Either they did not have it, we did not deserve

caviar, or there were no bugs in the walls.

Once upon a time, during a United Nations visit Ardeshir

Zahedi took me to take notes at a private meeting he had with the

US Secretary of State. The meeting took place at the US Mission

opposite to the UN headquartrers in New York. There was a pleasing

painting behind the Secretary of State and no one else but us in

the splendid room. While I was writing notes of the conversations,

a loud bang was heard from behind the painting! We got startled

but then said nothing. What was it, a misbehaving bug? I still wonder.

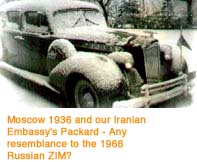

We left the immaculate little station in a

caravan of gleaming Zils (Russian limosines), Zims resembling old

American Packards, and an assortment of Tchaikas and Volgas. I was

assigned a better limo with Abbas Aram, the Minister of Foreign

Affairs, after all I was his private secretary. Instead, I jumped

in general Toufanian's modest volga. He is a jolly good fellow,

energetic and always enthusiastic about military hardware. Besides,

I did not want to hear the reprimands of the Minister of Foreign

Affairs on my snooping at the station. It did not take us too long

to arrive at Baikal. The view in front of us is stupendous, no wonder

outcast Lenin enjoyed it. I am assigned to a small chalet surrounded

with pine trees and overlooking the lake partially covered with

a light mist. We left the immaculate little station in a

caravan of gleaming Zils (Russian limosines), Zims resembling old

American Packards, and an assortment of Tchaikas and Volgas. I was

assigned a better limo with Abbas Aram, the Minister of Foreign

Affairs, after all I was his private secretary. Instead, I jumped

in general Toufanian's modest volga. He is a jolly good fellow,

energetic and always enthusiastic about military hardware. Besides,

I did not want to hear the reprimands of the Minister of Foreign

Affairs on my snooping at the station. It did not take us too long

to arrive at Baikal. The view in front of us is stupendous, no wonder

outcast Lenin enjoyed it. I am assigned to a small chalet surrounded

with pine trees and overlooking the lake partially covered with

a light mist.

Tania: a private official guide

It is in this idyllic romantic setting

that I met Tania. I had not quite settled in my room when she entered

the chalet. Are you "Gospadin (Mr.) Sepahbody?" Yes, "I

am tovaritch (comrade) Sepahbody," I answered, turning

towards the melodious voice. Truly, never had I seen such beauty.

Abundant dark blond hair, a youthful but somehow harsh face with

high cheek bones and the greenest slanted eyes in the world. She

looked willowy, tall and exotic. Surely she must have had some Mongolian

or Turcoman blood - after all we were not that far from Ulan Bator,

the capital of Mongolia. It is in this idyllic romantic setting

that I met Tania. I had not quite settled in my room when she entered

the chalet. Are you "Gospadin (Mr.) Sepahbody?" Yes, "I

am tovaritch (comrade) Sepahbody," I answered, turning

towards the melodious voice. Truly, never had I seen such beauty.

Abundant dark blond hair, a youthful but somehow harsh face with

high cheek bones and the greenest slanted eyes in the world. She

looked willowy, tall and exotic. Surely she must have had some Mongolian

or Turcoman blood - after all we were not that far from Ulan Bator,

the capital of Mongolia.

"Your baggage has arrived," she said in

a singing accented English."Where do you want me to put them?"

She delivered her words with a trace of haughtiness. Was it a sneer

I detected?

"No, no," I replied."leave the unpacking

to me; this is not a lady's job."

She would not listen. "My name

is Tania," she insisted, "and you must call me Tania.

I am your personal guide here." She sort of ordered me. "There

is Narzan mineral water, vodka, cigarettes, matches and Georgian

cognac if you are thirsty." She would not listen. "My name

is Tania," she insisted, "and you must call me Tania.

I am your personal guide here." She sort of ordered me. "There

is Narzan mineral water, vodka, cigarettes, matches and Georgian

cognac if you are thirsty."

God bless communism, I thought. But alas surely she must be a

KGB agent. I will never be able to approach her; what a shame. Photographing

a locomotive is one thing but befriending a pretty communist Mata

Hari on a state visit is another matter. End of career, imprisonment

if not worse -- for Western diplomats. As for Americans, forget

it; they'll have to face Congress, the Senate, FBI, CIA, and worst

of all their own wife!

My reveries were interrupted by Gholi Nasseri, an elderly gentleman

and close friend of the King. In Tehran he had the most amazing

collections of priceless Persian carpets. He had entered the room

without knocking, impeccably groomed, smartly dressed in a white

suit and wearing a felt hat as usual.

"Oh," he said,"I see that you are in excellent company;

ey sheytoun! (you rascal!). Are you up to your old Buenos-Aires

tricks?"

"No Sir, certainly not."

"Wait till I inform His Majesty." He bowed to Tania,

lifted his hat and left. I had no worries. Gholi and my father were

old friends.

In the meantime, Tania had opened my two Samsonite suitcases,

arranging the contents in drawers. I was surprised to see several

empty containers of 8mm films and a couple of American magazines.

I had thrown them in the dustbin at the Hotel in Moscow. In a brown

bag were also some plastic cigarillo tips! Amazing, it never entered

their mind that these items were worthless garbage. God knows how

they found their way back into my suitcases.

The empty film boxes and cigarillo tips were to follow me all

the way back to Tehran, no matter how many times I did away with

them. One time, while on a car trip from Bern, Switzerland

to Tehran, I was then a young embassy attache, we had stopped at

a Sofia hotel in communist Bulgaria. My wife Angela and I were having

dinner at a drab, sinister restaurant. When we returned to our room

late at night, the suitcases had been unpacked and guess what? My

Walther PKK revolver had been placed neatly on top of the bed's

pillow intimating, "be careful, we know." Thank God for

our diplomatic immunity.

Tania seemed immensely interested in my magazines, and I told her

she could have them.

"No, I can't take them, but I will have a look," she

said. Then she queried: "Do you need anything else?"

"No thank you very much Tania, I have all I need. Have a

nice evening."

She did not leave. Instead she sat down and read my magazines.

The Crypto cypher machine

I grab the attache case that never

left me and for very good reasons, it holds the Swiss Crypto cypher

machine. Our modern but complicated Swiss-made Crypto was based

on the old World War II German Enigma! I grab the attache case that never

left me and for very good reasons, it holds the Swiss Crypto cypher

machine. Our modern but complicated Swiss-made Crypto was based

on the old World War II German Enigma!

Lugging the darn thing and watching over it constantly was a major

pain. In Moscow, at a Kremlin state banquet I had dragged

the device all the way to the festive dinner of the heads

of state. I placed it next to my feet, under the table. At the end

of the banquet, when I looked for the machine it had disappeared.

I was in a state of total panic, a living a nightmare! Gholi Nasseri

who was sitting next to me had hidden it while I was speaking to

Foreign Minister Aram and placed it next to his own feet. A most

poisonous and nauseating trick. Later on, a journalist wrote

the story of a dedicated diplomat and his cypher machine in a Tehran

newspaper. The tale made the round at our Foreign Ministry.

Back to Baikal

It is dinner time . We are supposed to have

dinnner with His Majesty the King, the Queen and a few Russians.

They hosted an informal and relaxed dinner on the huge balcony overlooking

the lake. I ask directions from a Soviet plainclothes militiaman,

who accompanied us from Moscow. "It is not too far; I will

lead you." He sees me dragging the attache case and chuckles.

"Why do you always lug your machine everywhere?" It is dinner time . We are supposed to have

dinnner with His Majesty the King, the Queen and a few Russians.

They hosted an informal and relaxed dinner on the huge balcony overlooking

the lake. I ask directions from a Soviet plainclothes militiaman,

who accompanied us from Moscow. "It is not too far; I will

lead you." He sees me dragging the attache case and chuckles.

"Why do you always lug your machine everywhere?"

Then he proposes: "You can safely leave it in your room;

no one will ever touch it." Yeah, no one except you and surely

Tania or the KGB, I thought.

"I appreciate your great consideration," I replied,

"but there are rules and regulations I must obey, like you,

znayou?" He laughs and says, "you know if we

really want to peek into your briefcase we have ways of doing it

-- without you ever knowing!"

The sounds of balalaikas, violins and laughter fill the air as

we approach the terrace overlooking the majestic lake. Musicians

are wearing local costumes. Ladies are one side of the terrace,

men on the other. His Majesty is highly relaxed and smiling. He

seems to breathe intently the evening's fresh air. I have seldom

seen him that happy. And why shouldn't he be? It seems to be a very

successful trip and we have signed major agreements in Moscow.

Gholi Nasseri is standing close to the Shah and beckons me to come

closer. As I near His Imperial Majesty, he says, "Gholi told

us you already have managed to meet a gorgeous girl." Everyone

laughs except Aram the foreign minister whose motto was "Think

twice and then decide to say nothing."

"By the way," says the Shah pointing his finger at me,

"we know this Farhad quite well, do you still ski? How is your

father?" I replied with some adequate diplomatic niceties.

A bit later Alam confides: "Well let me tell you, you can

do anything in that department. If anyone coerces you, just relax

and say you have imperial permission." How considerate, but

I knew better. After all being a diplomat was a serious affair!

There is another general laughter. At dinner we were served a

unique Baikal fish, a rare delicacy. Unfortunately for the fish,

it was named "Omol" -- meaning tacky in Persian. That

too delighted everyone.Gholi Nasseri starts to sing Volga, in Russian.

Alam, the Court Minister joins him and everyone follows.

The singing over, Alam suddenly declares: "Grant it Your Majesty,

it is remarkable here, but what if they keep us in Baikal forever,

who would rescue us? Do you think anyone will miss us in Tehran

or elsewhere?"

The Shah is perplexed, "Hmm, probably not overly," he

answers jokingly, "but why would they do a thing like that?"

Once again there is resounding laughter.

Despite this unexpected, unsavory, observation, it is indeed a

very cheerful, engaging evening and our Soviet hosts are elated.

Mutual relations have never been that good! In Moscow the Russians

had said: "Why don't you send more Iranian students to our

country? They'll just study harder. You have forty thousand in America

and they return as nasty leftists troublemakers. Instead send them

to us and we guarantee that they will go back to Iran as good capitalists."

Indeed good humor was part of that memorable trip.

Later in the evening, at the Shah's dacha, I leave my black briefcase

to be watched over until morning by His Majesty's Iranian bodyguards.

Good Night Tania

As I enter my little chalet, I notice a slim silhouette outlined

against the bright moonlight. Slowly, I open the door leading to

the terrace. Tania, her fair hair flowing in the breeze, is watching

the glittering lake. I must say it was like poetry in motion. Beyond

the lake the crest of the Sayan mountains are outlined in a sky

full of bright stars.

Tania turns towards me, eyes as bright

as emeralds. "Do you like Russia," she asks looking straight

in my eyes. "I love mother Russia," I replied in Russian,

adding that I lived in Moscow for some four years when I was a child.

It was an excellent opportunity to practice my rusty Russian. In

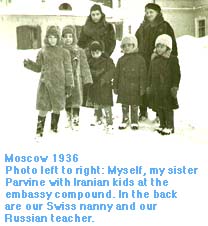

1936, my father was ambassador to the Soviet Union, during Stalin's

harshest years. She seems puzzled. We did not say anything and contemplated

the shiny moonlit lake. Tania turns towards me, eyes as bright

as emeralds. "Do you like Russia," she asks looking straight

in my eyes. "I love mother Russia," I replied in Russian,

adding that I lived in Moscow for some four years when I was a child.

It was an excellent opportunity to practice my rusty Russian. In

1936, my father was ambassador to the Soviet Union, during Stalin's

harshest years. She seems puzzled. We did not say anything and contemplated

the shiny moonlit lake.

"Let's go inside," I said. "It is getting chilly,

no time to catch cold."

"Yes," she approves.

Was it an impression? She really looks untamed, wild as a horse

of the steppes, her mane floating in the cool breeze. As she approaches

me, I feel a sudden all powerful, overwhelming rush to be close,

very close to her. Perhaps it is a call from my wild ancestral Qajar

blood. She must have sensed it: "I like the look in your eyes,

Farkhad." (Russians cannot pronounce "H"). I got

hold of my little transistor shortwave radio. "Come, let's

listen to some music."

Strangely enough, while I was searching for a station, the unjammed

Voice of America came out loud and clear -- and with just the right

blues tunes. A gift from Uncle Sam! The Cold War was very far away

and we reflected for a time. I offered her an American cigarette

and lit it. Frankly, I felt good lighting up an American cigarette

with Soviet matches.

Baikal and Persian Piff Paff

The next morning at around 7 am I have breakfast with Court Minister

Assadollah Alam and Abbas Aram the Foreign Minister. "Farhad

works hard and well," says Alam. "Besides, he knows quite

a few languages, including Russian. That's important. I am going

to take him to the Court. We need him there and that will be good

for his career."

"Oh no, no," replies Aram, who a year ago had lost his

clever, hardworking private secretary Parviz Raji to Amir Abbas

Hoveyda, the Prime Minister. In turn Hoveyda would lose him to Princess

Ashraf, twin sister of the Shah. "No! I won't allow this to

happen again," repeated Aram. Personally, I had no inkling

for either court, courtesans or courtiers.

Poor Abbas Aram, had puffy eyes, "Your Excellency, what happened?"

I asked.

"I was savaged, yes murdered by mosquitoes, there were millions

of them in my room."

"Me too," complains Alam, "And the Emshi (insecticide)

they gave us did not work; it just stank."

I knew how bad the mosquito problem was in Russia. From Tehran,

I had brought with me a precious can of Piff Paff, a strong Persian-made

insect killer. It blitzed the Siberian bugs straight out of the

air. By now the can was half empty and I was not about to surrender

this invaluable commodity. It was best to keep quiet. I would not

part with it, not even for a better job at the Ministry.. I already

had a good one.

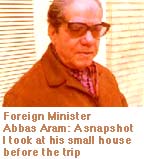

Aram, God bless his soul was an extremely

nice person, literate, compassionate, an avid reader, but also fussy

and a slave driver with his staff. But he also loved cats and that

was a formidable plus for me, a cat-lover. But Assadollah Alam was

the real power behind the throne, quick-witted, cunning, active

and a true Khan. When Khomeini initiated a bloody uprising in 1963,

the King was wavering and indecisive. In addition, shedding blood

was not his style. It is said that without the King's authorization,

Alam had called the troops and crushed the insurrection. Aram, God bless his soul was an extremely

nice person, literate, compassionate, an avid reader, but also fussy

and a slave driver with his staff. But he also loved cats and that

was a formidable plus for me, a cat-lover. But Assadollah Alam was

the real power behind the throne, quick-witted, cunning, active

and a true Khan. When Khomeini initiated a bloody uprising in 1963,

the King was wavering and indecisive. In addition, shedding blood

was not his style. It is said that without the King's authorization,

Alam had called the troops and crushed the insurrection.

Alam was decisive, manipulative, enigmatic, and never hesitated

to take action. Had he been alive in 1978, maybe the new uprisings

would have ended differently. Now, we shall never know. As for the

Shah, he was not willing to keep his throne through acts of violence,

which could have resulted in heavy loss of life.

Anyway, in October, following the Russian trip, Aram took me to

the UN General Assembly where on October 26, he gave a dazzling

reception in honor of Shahanshah's birthday. Dignitaries from everywhere

attended. There was champagne and Persian caviar galore. I always

liked to visit America, where I felt exhilarating freedom.

I pray for the rest of Aram's soul. This righteous and careful

diplomat, was thrown in jail during the revolution. He came out

of Evin's prison a broken man and died a few weeks later, hopefully

among his beloved cats and books.

Moscow

The long flight back to Moscow was exhausting, Rouhani, Minister

of Agriculture, fainted on the plane, probably from fatigue. Later

on he too would be executed by the Khomeini regime. Aram was sleeping

and Alam was writing notes on the trip. I asked him: "Do you

keep a journal, Sir?" He softly replied: "No, I only

keep notes, just in case His Majesty asks me what what we did and

said on this trip."

Many years later, after the Iranian Revolution, Alam's notes turned

into a book published by his daughters Naz and Rudy, The

Shah and I. The lively work describes the progress of Iran,

its many successes and the Shah's daily routine. Alam had

been Prime Minister during the dangerous and unstable early 1960s

and then Court Minister until his demise from cancer, just one year

before the revolution.

I saw him last, lying on a bed and looking very tired in a New

York hospital. In my teen years he used to visit our home, asking

for my father's advice. Alam was a friend of the Shah, since their

twenties. In retrospect I must say, he was uncommonly candid for

a Khan belonging to a culture that assuredly does not reward frankness.

From Moscow we went on to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg one more)

and then to Kiev and Yalta on the Black Sea. While in Moscow, I

took time to see the good old Persian Embassy with so many cherished

souvenirs of my mother, father and sisters.

My father was ambassador to the USSR in 1936, during the great

communist purges and  trials that ended in so many executions

or forced exile to the Gulag at best. Our embassy was located on

Pokrovsky Boulevard, No.7. It still is. When I visited Moscow on

that 1965 trip, nothing much had changed. The embassy looked the

same, gray and drab as always. A sort of large complex accommodating

the Ambassador's residence, offices, garages and staff buildings.

The whole compound was surrounded by tall walls. In the back a new

annex had been built. trials that ended in so many executions

or forced exile to the Gulag at best. Our embassy was located on

Pokrovsky Boulevard, No.7. It still is. When I visited Moscow on

that 1965 trip, nothing much had changed. The embassy looked the

same, gray and drab as always. A sort of large complex accommodating

the Ambassador's residence, offices, garages and staff buildings.

The whole compound was surrounded by tall walls. In the back a new

annex had been built.

The mansion housing the ambassador once belonged to a very rich

Russian countess. When a child, I had seen the old lady. She never

said much and worked as a concierge a sort of gate keeper. I thought

she was a witch. She watched the entrance of the embassy in a small

dwelling and opened the gates when ordered. My father told us that

she was probably obliged to report to the KGB whomever visited our

embassy. We were in the worst years of Stalin's bloody tyranny,

living as privileged diplomats, thank God. According to my father,

she had escaped the wrath of the Bolsheviks and a Soviet commissar

had allowed her to have this job at her former mansion as a gate

keeper. A sort of Doctor Zhivago story!

Prince Abbas Mirza and Princess Van of Georgia

When he was the Ambassador to the USSR, my father had adorned the

glittering grand ballroom of the embassy with a painting of Abbas

Mirza, his ancestor, and the gallant son of Fath Ali Shah Qajar.

He told us that once upon a time Abbas Mirza ruled the now Soviet

province of Georgia, a vassal of Persia during the Qajars. King

Heraclius (Irakli) of Georgia had allied himself with Prince Abbas

Mirza, our warrior ancestor. The Prince it was said, fell madly

in love with the king's beautiful daughter. She in turn adored the

dashing bejeweled young Persian Prince.

It was the perfect love story. They were seen riding beautiful

white horses, hunting and playing. The people of Georgia loved them.

More often they fought the Russians, together with the Prince and,

a grandson of Heraclius.

My father's painting was a diplomatic but constant reminder to

the Soviets that although lost, Georgia was still on our mind, as

the American song goes. At any rate it was good to see the old embassy

again with so many fond memories, especially of Bolshevo, on the

Volga, where we had a magnificent summer residence -- and so much

fun.

Anyway that's it for Russia.

Epilogue

Tania never ventured to quiz me and I wonder where she is now that

communism in her country has vanished, perhaps -- who knows -- forever?

Yes indeed, a diplomat's life is fraught with niceties but also

with some perils. Two of our diplomats Mr.X. in Bucharest, and Mr.

Z. in Berlin were arrested upon their return to Tehran. A secret

report from Western sources provided to Tehran, had accused them

of undue sympathies towards communists. They were tossed in jail

and only a timely intervention from the religious leaders in Tehran

saved them. Most of the time the Shah was very lenient; he forgave

and forgot.

Much later an American Ambassador asked me: "Why don't junior

Iranian diplomats mingle more often with ours?"

I jokingly replied: "If they venture anything foolish,

the next day it will be on our Minister's desk or worse."

My own conversations with the American ambassador in Morocco concerning

President Carter's lack of support for the Shah, were cabled to

the State Department and in turn, if relevant, dispatched to the

US embassy in Tehran. The Ambassador had replied that he believed

it to be "but a temporary aberration." I was shocked to

read one of the cables printed later in a book of shredded

US secret files reconstructed by so-called students who took over

the US embassy in Tehran after the revolution. Today they are on

an American site on the Internet!

At a Columbia University gathering of the eighties, I had an occasion

to converse with William Sullivan the last US Ambassador to Iran.

Among other matters, I queried him on the gross neglect and loss

of these secret US files which also put Iranian friends of America

at high risk.

"At the very outset of the Iranian Revolution," he replied,

"I had packed and shipped all these sensitive documents back

to the State Department in Washington. For a time they were clogging

the corridors of the State Department. But when State felt that

conditions were improving in Tehran, they shipped them back there

and that was a major mistake." Then, he jokingly ventured:

"Had I instead shipped these files to Columbia University,

it would have been much better for they would have been lost forever."

Anyway, when the revolutionaries unlocked the prison gates both

X. and also Z. who were awaiting a dire fate, disappeared into the

streets of Tehran. Iran also entertained excellent commercial relations

with Romania's Ceaucescu and the new Islamic Republic continued

the same trend. Unfortunately for Ceaucescu, a few days after his

state visit to Iran, he was executed by his people.

The Shah appreciated the Romanians. He delivered one of his best

speeches while in Bucharest on a state visit. He had declared: "In

Iran, we much prefer the Canons of Law to the to the canons of War."

I was present and got a Theodor Vlamiderescu decoration from Ceaucescu.

On that noteworthy occasion we also visited the foreboding castle

of Dracula (Draghul) believed to be replete with vampires. The menacing

castle was unlocked exclusively for us. This was straight out of

a Bela Lugosi horror movie.

Returning home

State visits had their good side,

when we relaxed, spoke unofficially to hosts, took long, calm strolls

with them, getting to know their views better, spreading out our

own hopes, exchanging ideas and making deals. You have to be at

ease and serene. It is when visiting museums, getting a grip of

history, talking to people, centering on the human element, quietly

exchanging views that you reach understanding and, finally, an agreement. State visits had their good side,

when we relaxed, spoke unofficially to hosts, took long, calm strolls

with them, getting to know their views better, spreading out our

own hopes, exchanging ideas and making deals. You have to be at

ease and serene. It is when visiting museums, getting a grip of

history, talking to people, centering on the human element, quietly

exchanging views that you reach understanding and, finally, an agreement.

At the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad we were shown a fantastic

collection of French modern paintings never displayed to the

Russian public. The Soviets also showed us some of the many priceless

jewels Nader Shah had sent to the Tsar. The museum curator divulged

that at one time Nader Shah (The Napoleon of Persia) had asked for

the hand of a Russian princess but got a dissenting reply due to

his humble origin. When a Russian envoy had asked about the King's

parents, a piqued Nader Shah, the conqueror of India and other lands

replied, "I am the Son of my Sword." He surely gave the

right answer. I for one was proud of his impressive response.

Now in faraway Sedona, Arizona, all those days seems so distant,

as if they never happened at all. But here is a test to find

out whether one's mission on earth is finished. If you're still

alive, it isn't! So be present in life, right now, at this very

moment, because nothing else really exists. The past is gone and

the future isn't here yet. As Omar Khayyam said, "Do not fret

on the day that hasn't come or the day that has passed."

One last note, all of

our state visits were quite successful, including the one to the

Soviet Union where we signed the famed Isfahan Steel Mill deal.

No small feat and a lot of work. Even today it still produces lots

of steel, and that's just a tiny part of our legacy for prosperity

and peace. In the final analysis, if we did fail, it was not because

of lack of enterprise but perhaps because of overreaching

-- too much too fast. One last note, all of

our state visits were quite successful, including the one to the

Soviet Union where we signed the famed Isfahan Steel Mill deal.

No small feat and a lot of work. Even today it still produces lots

of steel, and that's just a tiny part of our legacy for prosperity

and peace. In the final analysis, if we did fail, it was not because

of lack of enterprise but perhaps because of overreaching

-- too much too fast.

Author

Farhad Sepahbody was Iran's last ambassador to

Morocco under the Pahlavi Dynasty.

* Send

this page to your friends

* Printer

friendly

|