India's Parthian

colony India's Parthian

colony

On the origin of the Pallava empire of Dravidia

By Dr. Samar Abbas, India

May 14, 2003

The Iranian

This paper reveals the ancient Pallava Dynasty of Dravidia

to be of the Iranic race, and as constituting a branch of the Pahlavas,

Parthavas or Parthians of Persia. It uncovers the consequent Iranic

foundations of Classical Dravidian architecture. It also describes

a short history of the Pallavas of Tamil Nadu, including the cataclysmic

100-Years' Maratha-Tamil War. The modern descendants of Pallavas

discovered amongst the Chola Vellalas of northern Tamil Nadu and

Reddis of Andhra. (Some names in this text are garbled.

The Word document characters could not be converted.)

1. Pallavas, Pahlavas, Parthavas, Parthians and Persians

1.1. Introduction

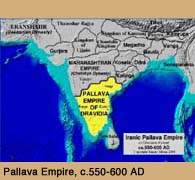

The Pallava Empire was the largest and most powerful South Asian

state in its time, ranking as one of the glorious empires of world

history. At its height it covered an area larger than France, England

and Germany combined. It encompassed all the present-day Dravidian

nations, including the Tamil, Telugu, Malayali and Kannada tracts

within its far-flung borders (larger

map).

The foundations of classical Dravidian architecture were established

by these powerful rulers, who left behind fantastic sculptures and

magnificent temples which survive to this very day. Initially, the

similarity of the words "Pallava" and "Pahlava" had led 19th-century

researchers to surmise an Iranic origin for the Pallavas. Since

then, a mountain of historical, anthropological, and linguistic

evidence has accumulated to conclusively establish that the Pallavas

were of Parthian origin.

1.2. Occurrence of Parsas across the world

The wide occurrence of the Iranic root-word Par in various place-names

proves the dispersion of the Pars or Persians across much of Asia

in ancient times. Thus, Persia, Persepolis, Pasargadae ("Gates of

Parsa") and "Parthaunisa (ancient city, Parthia)" or Nisa (Enc.

Brit., vol.9, p.173) are all constructed from the ancient Iranic

root-word Pars.

In this regard, the learned Prof. Waddell notes in his masterpiece

The Makers of Civilization: "Barahsi or Parahsi [of Akkadian

inscriptions] now transpires to be the original of the ancient Persis

province of the Greeks, with its old capital at Anshan or Persepolis,

the central province of Persia to the East of Elam and the source

of our modern names of 'Persia' and 'Parsi'. And it is another instance

of the remarkable persistence of old territorial names" (Waddell

1929, p.216).

The Parsumas mentioned in Assyrian annals are also generally

identified with the Persians, and the Zoroastrian Parsis of Maharashtra

are clearly of Persic descent. Moreover, the word Parthian is itself

derived from Parsa, as the Encyclopedia Britannica notes:

"The first certain occurrence of the name is as Parthava in the

Bisitun inscription (c.520 BC) of the Achaemenian king Darius I,

but Parthava may be only a dialectal variation of the name

Parsa (Persian)." (Enc.Brit. Vol.9, p.173)

Professor Michael Witzel of Harvard University has further identified

the Parnoi as the Pani mentioned in the Vedas:

"Another North Iranian tribe were the (Grk.) Parnoi,

Ir. *Parna. They have for long been connected with another

traditional enemy of the Aryans, the Paṇi (RV+). Their

Vara-like forts with their sturdy cow stables have been compared

with the impressive forts of the Bactria-Margiana (BMAC) and the

eastern Ural Sintashta cultures (Parpola 1988, Witzel 2000), while

similar ones are still found today in the Hindukush." (Witzel 2001,

p.16)

Thus, the Persians, Parthians, Pashtos, Panis and Perizzites are all

offhoots of the ancient proto-Persians. This testifies to the achievements

of the Persian branch of the Iranic race in civilizing and colonizing

Southern Asia. All this, of course, is well known and the subject

of numerous books (cf, eg. Derakhshani 1999). Less famous is the fact

that the magnificent Pallava Dynasty of Southern India was also of

Iranic descent.

1.3. Pahlava History in Iran

The Pahlavas made important contributions to Iranian civilization.

The modern Farsi tongue is derived from the Old Parthian language,

as noted by the Encyclopedia Britannica: "Of the modern

Iranian languages, by far the most widely spoken is Persian, which,

as already indicated, developed from Middle Persian and Parthian,

with elements from other Iranian languages such as Sogdian, as early

as the 9th century AD." (Enc.Brit.vol.22, p.627) Furthermore, "Middle

Persian [Sassanian Pahlava] and Parthian were doubtlessly similar

enough to be mutually intelligible." (Enc.Brit.22.624); a statement

which further confirms the identity of the Pahlavas and the Parthians.

Moreover, the Pahlava alphabet is the ancestor of the Sasanian

Persian alphabet: "The Pahlava alphabet developed from the Aramaic

alphabet and occurs in at least three local varieties: northwestern,

called Pahlavik or Arsacid; southwestern, called Parsik or Sasanian,

and eastern" (Enc.Brit. vol.9, p.62).

Some authorities seem to insist that it was the Semitic Aramaic

alphabet which gave birth to the Parthian alphabet. This is not

so; it was actually the Assyrian variant which developed into the

Pahlava characters, just as it was Assyrian art, not Aramaean, which

inspired later Achaemenid culture. The Achaemenid empire was in

many ways the successor-state of the Assyrian empire.

1.4. Pallavas of Dravidia as Pahlavis

The Pallavas are first attested in the northern part of Tamil Nadu,

precisely the geographical region expected for an invading group.

This, together with the evident phonetic similarity between the words

"Pallava" and "Pahlava", has long led researchers to advocate a Parthian

origin of the Pallavas:

"Theory of Parthian origin: The exponents of this theory

supported the Parthian origin of the Pallavas. According to this

school, the Pallavas were a northern tribe of Parthian origin constituting

a clan of the nomads having come to India from Persia. Unable to

settle down in northern India they continued their movements southward

until they reached Kanchipuram5. The late Venkayya supported

this view 6 and even attempted to determine the date

of their migration to the South. A crown resembling an elephant's

head was issued by the early Pallava kings and is referred to in

the Vaikunthaperumal temple sculptures at the time of Nandivarman

Pallavamalla's ascent to the throne. A similiar crown was in use

by the early Bactrian kings in the 2nd century BC and figures on

the coins of Demetrius. It is presumed on this basis that there

is some connection between the Pallavas of Kanchi and Bactrian kings.

[5. Mysore Gazetteer, I. p.303-304; 6. ASR {Ann.Rep.ASI), 1906-1907,

p.221 ]." (Minakshi 1977, p.4)

As Venkayya notes,

"[T]he Pallavas of Kāñcīpuram

must have come originally from Persia, though the interval of

time which must have elapsed since they left Persia must be several

centuries. As the Persians are generally known to (p.220) Indian

poets under the name Pārasīka, the term Pahlava or

Pallava must denote the Arsacidan Parthians, as stated

by Professor Weber." (Venkayya 1907, p.219-220)

Philogists concur in connecting the names Pahlava, Parthava, Parthian

and Pallava:

"The word Pahlava, from which the name Pallava

appears to be derived, is believed to be a corruption of Pārthava,

Pārthiva or Pārthia, and Dr. Bhandarkar calls the Indo-Parthians

Pahlavas. The territories of the Indo-Parthians lay in Kandahar

and Seistan, but extended during the reign of Gondophares (about

AD 20 to 60) into the Western Punjab and the valley of the lower

Indus. The Andhra king Gotamiputra, whose dominions lay in the Dakhan,

claims to have defeated about AD 130 the Palhavas along with the

Śakas and Yavanas. In the Junāgaḍh inscription

of the Kṣatrapa king Rudradāman belonging to about AD

150, mention is made of a Pallava minister of his named Suviśākha."

(Venkayya 1907, p.218)

2. Evidence for Parthian Descent of Pallavas

A whole mountain of evidence from various fields of science support

the Parthian, and hence Iranic, origin of the Pallavas. It would be

of interest to summarise the evidence here.

2.1. Archaeology

Archaeologists note the occurrence of oblong earthenware coffins in

sites coinciding with the region of Pallava hegemony:

"Oblong earthenware sarcophagi, both mounted

and unmounted, have been reported from several sites in S. India

from Maski in the North to Puduhotta in the South. Their distribution

in what was during historical period the region of Pallava hegemony

is not without significance in the light of a Parthian

origin of the Pallavas suggested by Heras (Heras, H.J.: Origin of

the Pallavas, J. of the Univ. of Bombay, Vol. IV, Pt IV, 1936) and

afterwards by Venkatasubba Iyer ("A new link between the Indo-Parthians

and Pallavas of Kanchi", J. of Indian History, Vol. XXIV, Pts

1 & 2, 1945).

2.2. Administration

Pallava administration was based on the Maurya pattern, which was

in turn based on that of the Achaemenid Empire.

"[T]he early Pallava kings issued their charters in Prakrit

and Sanskrit and not in Tamil and their early administration was

based on the Mauryan-Satavahana pattern, essentially northern in

character. Their gotra (Bharadvaja) also stands in the way of their

identification with the Kurumbar who had no gotra claims." (Minakshi

1977, p.5)

2.3. Dress

The dress of the Pallavas is cleary Parthian. Thus, Nair notes,

A possible link between the Parthians and the

Pallavas is the mode of tying the waist-band as evidenced by their

statuary (compare the knot in Pallava waist-band with knot in Parthian

waist-band ...)" (Nair 1977, p.85)

The entire city of Mamallapuram or Mahamallapuram in Tamil Nadu

is named after the Pallava King Mahamalla who is celebrated as the

founder of this city. This original Prakrit name "Mahamallapuram"

was later corrupted in the Sanskrit into "Mahabalipuram". In this

regard, Venkayya notes the origin of the name "Mamallapuram":

"[I]n ancient Cōḍa inscriptions found at

the Seven Pagodas, the name of the place is Māmallapuram which

is evidently a corruption of Mahāmallapuram, meaning `the

city or town (p.234) of Mahāmalla.' I have already mentioned

the fact that Mahāmalla occurs as a surname of the Pallava

king Narasiṁhavarman I in a mutilated record at Bādāmi

in the Bombay Presidency. It is thus not unlikely that Mahāmallapuram

or Māvalavaram was founded by the Pallava king Narasiṁhavarman,

the contemporary and opponent of the Calukya Pulikēśin

II., whose accession took place about AD. 609. Professor Hultzsch

is of opinion that the earliest inscriptions on the rathas are birudas

of a king named Narasiṁha. It may, therefore, be concluded

that the village was originally called Mahāmallapuram or Māmallapuram,

after the Pallava king Narasiṁhavarman I., and that the earliest

rathas were cut out by him." (Venkayya 1907, p.233-234)

Surviving contemporary sculptures of this celebrated King Mamalla

depict him wearing a typical cylindrical Iranian head-dress:

Fig.2: Pallava King Mamalla or Narasimhavarman I

(Dharmaraja Ratha, Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu)

Note the cylindrical Persian hat, long thin nose and long-headedness.

(Image by Michael D. Gunther)

Furthermore, the elephant-head crown used by Pallava kings resembled

those worn by Bactrian kings (cf. Appendix I).

2.4. Prakrit Language

The Pallavas initially propagated Prakrit, a language containing a

much higher percentage of Indo-European words compared to Sanskrit

as it represented a later, and hence purer, heliolatric Indo-European

invasion. "These three Prākṛt grants prove that there

was a time when the court language was Prākṛt even in

Southern India." (Venkayya 1907, p.223) That they initially did not

propagate Sanskrit or Tamil is significant as it rules out a Vedic

or Dravidian origin for the Pallavas.

2.5. Toponyms and Personal Names

Evidence from toponyms (place-names) corroborates the Iranic origin

of Pallavas. For instance, the Pallavas named a city in Tamil Nadu

as Menmatura or Men-Matura, after Mithra, the ancient Iranic Sun-God,

formed from tbe consonantal root MTR. The large town in southern

Tamil Nadu, Madurai, is named after the Sun-temple city of Mathura

in Oudh, which is also based on "Mithra". Further, the Pallavas

had a fondness for Iranic Prakrit personal names such as Ashoka:

"In the Kāśākuḍi plates, Aśōkavarman

is referred to as the son of king Pallava. Here Aśōkavarman

is evidently a reminiscence of the Maurya emperor Aśōka

who lived long before the Pallavas." (Venkayya 1907, p.240, footnote

8).

The Pallavas thus sought to emulate the Maurya kings, who were

of Iranic origin (Spooner 1915, p.406ff). It is important to note

that the Iranic root-word "Mor" occurs all across the Iranian world:

consider the "Mardian" tribe of Persians mentioned by Herodotus;

"the Avestan name Mourva, the Marga of the Achaemenian inscriptions"

(Spooner 1915, p.406), and the city of Merv, also known as "Merw,

Meru or Maur", whose inhabitants are known as "Marga and Mourva"

(ibid.), the legendary "Meru" mountain, the "Amorites" or "Amurru"

of Syria and Palestine who possessed an Iranic ruling caste, the

"Amu-Darya" river, "Amol" town just south of the Caspian, "Marwar"

in Rajputana, the Oudh towns of "Mor-adabad" and "Meerut", the "Maurya"

dynasty of Ashoka, and the "Marut" warriors in India.

2.6. Official Symbolism

To this evidence we may add that the Pallavas had as their crest

the lion, just as the Achaemenids carved lions at Persepolis. Describing

the cave at Siyamangalam, Venkayya notes:

"This was excavated by king Laḷitāṅkura,

ie. Mahēndravarman I. and was called Avanibhājana-Pallavēśvara,

Ep.Ind., Vol.VI, p.320. I recently inspected the cave and

the two inscriptions found in it. The two outer pillars of the cave

on which they are engraved also bear at the top a well-executed

lion (one on each of the two pillars) with the tail folded over

its back. The tail resembles that of the lion figured in No.54,

Plate II. of Sir Walter Elliot's Coins of Southern India,

which has been attributed to the Pallavas. It has therefore to be

concluded that the lion was the Pallava crest at some period or

other of their history." (Venkayya 1907, p.232, ftn.6)

2.7. Anthropology

The depictions of Pallava nobles on sculptures further confirms

their Iranic origin, for they are depicted as tall and dolichocephalic

(long-headed) along with clearly Iranic features.

Fig.3: Court Scene, Mamallapuram 7th century AD

(Pallava)

Note the long-headedness and leptorrhine (long and thin)

nose of the surrounding Iranic courtiers. Contrast this with

the platyrrhine (flat) nose, thick lips and Negroid features

of the Dravidian God Shiva standing with his bull in the

centre. Note clear Persepolitan influence on the pillars.

(Image by Michael D. Gunther)

Larger

image

The long-headedness of these sculptures rules out an Outer Indo-Aryan

origin for the Pallavas, while their leptorrhine noses rule out

a Dravidian origin.

2.8. Architecture

The architecture of the Pallavas was clearly based on Iranian

forms, down to the last detail. Pillars especially were copies of

Persepolitan originals (see Fig.4 and Fig.3).

Fig.4: Varaha Cave Temple, Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu,

late 7th century. Note the clear Achaemenid influence

on the pillars, and the Persepolitan capitals. Flanking

lions are reminiscent of Persepolis and Assyria.

(Image by Michael D. Gunther)

Larger

image

2.9. Legendary Descent

The traditional genealogy of the Pallavas also points to their

Parthian origins:

"One point which might be taken as proof of the foreign

origin of the Pallavas has to be noted here. The indigenous Kṣatriya

tribes (or at least those which were looked upon as such) belonged

either to the solar or to the lunar race. For instance, the Cōḷas

belonged to the solar race and the Pāṇḍyas to

the lunar. The Cēras seem to have belonged to the solar race.

The Calukyas - both the Eastern and Western - were of the lunar

race. The Rāṣṭrakūṭas were also of

the same race. On the other hand, the Pallavas trace their descent

from the god Brahma but not from the Sun or the Moon, though they

are admitted to have been Kṣatriyas. Besides, none of the

ancient kings mentioned in the Purāṇas figures in the

ancestry of the Pallavas. The indigenous tribes, however, always

traced their ancestry from some of the famous kings known from the

Purāṇas. The Cōḷas, for instance claimed

Manu, Ikṣvāku, Māndhātr, Mucukunda and Śibi;

the Pāṇḍyas were descended from the emperor Purūravas;

the C ēras had Sagara, Bhagiratha, Raghu, Daśaratha

and Rāma for their ancestors. The Calukyas had a long list

of Purāṇic sovereigns in their ancestry. The Rāṣṭrakūṭas

were descendants of Yadu and belonged to the Sātyaki branch

or clan. The Gaṅga kings of Kaliṅganagara were descended

from the Moon and claimed Purūravas, Āyus, Nahuṣa,

Yayāti and Turvasu for their ancestors. (Ind. Ant.

Vol. XVIII, p.170). The Western Gaṅgas of Taḷakāḍ

were apparently of the solar race and had Ikṣvāku for

their ancestor (Mr Rice's Mysore Gazetteer, Vol.I, p.308).

The only king mentioned in the mythical genealogy of the Pallavas

is Aśōkavarman, son of king Pallava , who, as Prof.

Hultzsch rightly suspects, is probably "a modification of the Maurya

emperor Aśōka" (South Ind. Inscrs. Vol.II, p.342).

No doubt the earliest Pallava records were found in the Kistna delta.

But this cannot be taken to point to an indigenous origin of the

family. All these facts together raise the presumption that the

Pallavas of Southern India were not an indigenous tribe in the sense

that the Cōḷas, Pāṇḍyas and Cēras

were." (Venkayya 1907, p.219, footnote 5)

The above evidences, taken together rather than singly, provide

almost conclusive proof of the Parthian origin of Pallavas.

3. History of the Pallavas

3.1. Early History: Adoption of Dravidian Culture

After immigrating from Parthia, the Pallavas settled down in the

Andhra region. From here they entered northern Tamil Nadu. Initially,

the Pallava Empire was restricted to Toṇḍai-maṇḍalam,

the northern part of Tamil Nadu: "It thus appears that the Pallava

dominions included at the time [Sivaskandavarman, beg. 4th century

AD] not only Kāñcipuram and the surrounding province

but also the Telugu country as far north as the river Kṛṣṇā."

(Venkayya 1907, p.222) Subsequently, the Pallavas expanded to conquer

large parts of Andhra:

"The Pallava dominions probably comprised at the time

[5th-6th centuries AD] the modern districts of (p.225) Nellore,

Guntur, Kistna, Kurnool and perhaps also Anantapur, Cuddapah, and

Bellary. The Kadambas of Banavāsi, who were originally Brāhmaṇas,

threatened to defy the Pallavas." (Venkayya 1907, p.224-225)

Tamil poets described the boundaries of Toṇḍai-maṇḍalam

as follows:

"According to the Toṇḍamaṇḍala-śatakam,

Toṇḍamaṇḍalam (ie. the Pallava territory)

was bounded on the north by the Tirupati and Kālahasti mountains;

on the south by the river Pālār; and on the west by

the Ghauts (Taylor's Catalogue, Vol.III, p.29). A verse attributed

to the poetess Auvaiyār describes Toṇḍai-maṇḍalam

as the country bounded by the Pavaḷamalai, ie. the Eastern

Ghauts in the west; Vēṅgaḍam, ie. Tirupati in

the north; the sea to the east; and Piṇāgai, ie. the

Southern Pennar in the south. The greatest length of the province

is said to be full 20 kādam or nearly 200 miles.... A variant

of the name Toṇḍai-maṇḍalam is Daṇḍaka-nāḍu,

which is apparently derived from the Sanskrit Daṇḍakāraṇya,

ie the forest of Daṇḍaka mentioned in the Rāmāyaṇa

and the Purāṇas." (Venkayya 1907, p.222, footnote 2)

After settling in Tondai-mandalam, the Pallavas rapidly adopted

the Dravidian culture, religion and language of their subjects.

This case was not unique in history; there are many examples of

ruling classes adopting the culture of those they ruled: consider

the Hellenic Ptolemies in Egypt, the Paleo-Siberian Manchus in China,

the Germanic Lombards in Italy, the Nordic Visigoths in Spain, the

Mongol Il-Khans in Persia, the French-speaking Normans in England,

and the Germanic Carolingians, Merovingians, Burgundians and Franks

of France. Thus, the Pallavas adopted the Old Tamil language and

the Dravidian religion of Shaivism and became vigorous promoters

of Dravidian culture.

3.2. Expansion of the Pallava Empire

From its nucleus in Tondaimandalam, the Pallava Empire expanded

in all directions. The Pan-Dravidian nature of the Pallava empire

is manifested through the extent of their dominions. Thus, the Pallavas

vanquished the Cholas, Cheras and Pandyas and conquered their territories,

uniting Tamil Nadu, Malabar, Karnadu and Telingana into one giant

empire:

"The earliest king of this series is Siṁhaviṣṇu,

who claims to have vanquished the Malaya, Kalabhra, Mālava,

Cōḷa and Pāṇḍya kings, the Siṁhala

king proud of the strength of his arms and the Kēralas." (Venkayya

1907, p.227)

This was the first pan-Dravidian empire in history. Perhaps they were

able to unite the Dravidian nations precisely because they were outsiders,

and hence did not possess any history of feuding with local clans.

Thus, we find the Pallavas conquering all the three mutually warring

Pandya, Cola and Cera kingdoms:

"The Cēra, Cōḷa and Pāṇḍya

kingdoms of the south are mentioned already in the edicts of the

Maurya emperor Aśōka. Of their subsequent history, almost

nothing is known from the epigraphical records, until we get to

the period of Pallava rule, when all the three figure among the

tribes conquered by the Pallavas." (Venkayya 1907, p.237)

After consolidating their rule over the Dravidian nations, the Pallavas

extended their empire to South-East Asia:

"The Pallavas were the emperors of the Dravidian country

and rapidly adopted Tamil ways. Their rule was marked by commercial

enterprise and a limited amount of colonization in South-East Asia,

but they inherited rather than initiated Tamil interference with

Ceylon." (Enc.Brit. Vol.9, p.89)

However, the exact extent of Pallava colonization in South-East

Asia is not clear due to paucity of sources. Even so, the Pallava

Empire was the largest South Asian state of its age, and served

as the model for future pan-Dravidian empires such as that built

by the Cholas.

3.3. The 100-Years' Maratha-Tamil War (AD 634-747) & Decline

The Indian equivalent of Europe's Anglo-French 100-Years' War was

the prolonged conflict between Marathas and Tamils under the Chalukyas

and Pallava dynasties which lasted well over a century.

"The history of this period consists mainly of the events of

the war with the Calukyas which lasted almost a century 7

(footnote 7: The war apparently began with the Eastern campaign

of Pulikēśin II. which must have taken place some

time before AD 634-5 (Ep.Ind., Vol.VI, p.3). The last important

event of the war is the invasion of Kāñci by the

Calukya king Vikramāditya II, who reigned from AD 733-4

to 746-7. Kirtivarman II, son of Vikramaditya II, also claims

to have led an expedition in his youth against the Pallavas. ...

) and which seems to have been the ultimate cause of the decline

and downfall of both the Pallavas and Calukyas about the middle

of the 8th century." (Venkayya 1907, p.226)

At this point, we may note Mr. Rice's hypothesis that the Calukyas

were Seleucids:

"Mr. Rice says: `The name Calukya bears a suggestive

resemblance to the Greek name Seleukeia, and if the Pallavas were

really of Parthian connection, as their name would imply, we have

a plausible explanation of the inveterate hatred which inscriptions

admit to have existed between the two, and their prolonged struggles

may have been but a sequel of the contests between the Seleucidæ

and the Arsacidæ on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates.'

(Mysore, Vol.I, p.320)" (Venkayya 1907, p.226, footnote 6)

However, Mr. Rice's suggestion has not been accepted by other

historians, and is merely a phonetic coincidence, for there is no

other evidence of any connection whatsoever between the Calukyas

and Seleucids.

Historians have found several reasons for explaining the bitterness

of the Maratha-Dravidian wars. Venkayya notes the religious aspect

of the conflict, with the Vaishnava Marathas on one side and the

Dravidian Shaivites on the other:

"No satisfactory explanation has, so far, been offered

for this natural enmity between the Pallavas and Calukyas. It is

possible that the hatred had a religious basis. The Pallavas were

Śaivas and had the bull for their crest, while the Calukyas

were devotees of the god Viṣṇu and had the bear for

their crest." (Venkayya 1907, p.226, footnote 6)

Shaivism and Vaishnavism are poles apart in all details of theology.

Vaishnavites revere the cow, Shaivites slaughter the cow but worship

the bull; Vaishnavites uphold the four-fold caste system, Shaivites

oppose the caste system tooth and nail; later Vaishnavism upholds

the authority of the Vedas and the Brahmans, Shaivism rejects the

Vedas and is anti-Brahmin. Thus, observers have noted that Vaishnavism

and Shaivism are like cat and mongoose, theologically destined to

be locked in an eternal war of opposites. Hence, religion played an

important role in exacerbating the hatred on both sides.

However, a far deeper reason contributed to the conflict, namely

that of ethnicity. Abstract theological formulae, on account of

their nebulous definition and easily modified nature, no doubt hardly

mattered to the great majority of inhabitants. Rather, it is race

and ethnicity which combined to make the Pallava-Chalukya conflict

especially bitter. Thus, the so-called Calukya-Pallava dynastic

conflict was in actual fact a racial Maratha-Dravidian war.

On the one hand were the Marathas speaking Outer Indo-Aryan languages,

of brachycephalic (round-headed) Turanoid race. The survival of

Burushaski - a language isolate linked with the Transcaucasian and

Finno-Ugric languages - in the Himalayas testifies to the immigration

of brachycephalic Turanian peoples into India. The Turanoid Maratha

is thus fair-skinned, short-statured and round-headed. On the other

hand were the long-headed and taller, black-skinned Dravidians of

Sudanic Negroid origin. The Dravidians, however, had a long-headed

Iranic Pallava ruling class. The Iranoid longheads are fairer and

taller than the Dravidoid longheads, who are in turn taller but

darker than the Turanoid Outer Indo-Aryan roundheads. Thus, racial

differences no doubt played, along with language and religion, a

prominent role in the conflict.

At the outset of the 100-year Maratha-Tamil War, it is the Marathas

who gained the upper hand, defeating the Pallavas and driving them

from the Vengi delta area of Andhra. However, the Pallavas later

defeated the Maharashtrians and sacked their capital Vatapi, annexing

it to the Dravidian Empire:

"The son of Mahēndravarman I. was Narasiṁhavarman

I., who retrieved the fortunes of the family by repeatedly defeating

the Cōḷas, Kēralas, Kalabhras and Pāṇḍyas.

He also claims to have written the word `victory' as on a plate,

on Pulikēśin's back, which was caused to be visible

(ie. which was turned in flight after defeat) at several battles.

Narasiṁhavarman carried the war into Calukya territory

and actually captured Vātāpi, their capital. This claim

of his is established by an inscription found at Bādāmi

in the Bombay Presidency - the modern name of Vātāpi

- from which it appears that Narasiṁhavarman bore the title

Mahāmalla. In later times, too, this Pallava king was known

as Vātāpi-koṇḍa-Naraśiṅgappōttaraiyan.

Dr. Fleet assigns the capture of the Calukya capital to about AD

642. 7 The war of Narasiṁhavarman with

Pulkēśin II is mentioned in the Singhalese chronicle

Mahāvaṁsa. It is also hinted in the Tamil Periyapurāṇam.

The well-known saint Śiṛuttoṇḍa, who had

his only son cut up and cooked in order to satisfy the appetite

of god Śiva disguised as a devotee, is said to have reduced

to dust the city of Vātāpi for his royal master, who

could be no other than the Pallava king Narasiṁhavarman.9

[footnote 9: Ep.Ind. Vol.III, p.277. . Paramēśvaravarman

I. also claims to have destroyed the Calukya capital. A still later

conquest of Vātāpi is also known. It was effected by

a Koḍumbāḷūr chief, apparently during the

second half of the 9th century. (Ann.Rep. on Epi. for 1907-8, Part

II, para.85)] The Śaiva saint Tiruñānasambandar

visited Śiṛuttoṇḍa at this native village

fo Tirucceṅgāṭṭaṅguḍi, and the

Dēvāra hymn dedicated to the Śiva temple of the

village mentions the latter and thus helps to fix the date of the

former as well as of the Śaiva revival of which he was the

central figure." (Venkayya 1907, p.228)

Unsung and forgotten are the countless heroes on both sides, their

deeds and brave acts lost in the mist of time, yet heroes they were

nevertheless. Like the knights of the 100-Years' Anglo-French War,

the glorious warriors of the 100-Years' Maratha-Tamil War fought

and died for their homelands, strengthening these nations' foundations

with their blood and bones.

This 100-year Maratha-Tamil war had far-reaching consequences,

leading to the exhaustion of both the Maratha and Dravidian states

and sapping their vitality. These states started to decline after

the war. Ultimately, both the Calukya and Pallava states disappeared

from history.

3.4. Modern-Day Pallavas

After the Pallava Empire was annexed by the Chola Empire, the Pallavas

merged into the Tamil population:

"The Pallavas of the Tamil country seem to have taken

service under the Cōḷas after the Gaṅga-Pallavas

were conquered by Āditya about the end of the 9th century

AD. Karuṇākara Toṇḍaimāṇ, who,

according to the Tamil poem Kaliṅgattu-Paraṇi led the

expedition against Kaliṅga during the reign of Kulōttuṅga

I. (AD 1070 to about AD 1118), was a Pallava and was the lord of

Vaṇḍai, ie. Vaṇḍalur in the Chingleput District.

Among the vassals of Vikrama-Cōḷa mentioned in the Vikkirama-Śōḷaṇ-ulā,

the Toṇḍaimāṇ figures first." (Venkayya

1907, p.241)

The Pudukkottai royal family is apparently descended from the ancient

Pallavas:

"In a Tanjore inscription belonging to a later period,

the name Toṇḍaimāṇ is applied to a local

chief named Sāmantanārāyana, who granted to Brāhmaṇas

a portion of the village of Karundiṭṭaiguḍi, the

modern Karattaṭṭāṅguḍi. Thus the name

Toṇḍaimāṇ actually travelled from the Pallava

into the Cōḷa country. There is therefore reason to

suppose that the Toṇḍaiman of Pudukkōṭṭai,

who bears the title Pallava Raja, is descended from the Pallavas,

who form the subject of this paper." (Venkayya 1907, p.242)

In addition to the royal family of Pudukkottai, other groups are also

probably descended from the Pallavas, such as the Reddis of Andhra

and some of the Kshatriya and Vaishya castes of northern Tamil Nadu:

"We now have to examine if there are any Pallavas in

our midst beyond the royal family of Pudukkōṭṭai.

The Pallavas are believed to be identical with the Kurumbas, of

whom the Kurumbar of the Tamil country and the Kurubas of the Kanarese

districts and of the Mysore State may be taken as the living representatives.

The (p.243) kings of the Vijayanagara dynasty are also supposed

to have been Kurubas. In one of the inscriptions of the Tanjore

temple belonging to the 11th century, a certain Vēlāṇ

Ādittaṇ is called Pirāntaka-Pallavaraiyan, meaning

"the chief of the Pallavas of Parāntaka." Śēkkiḷār,

the author of the Tamil Periyapurāṇam, was a Veḷḷāḷa

by caste and got from his patron, the Cōḷa king Anapāya,

the title Uttamaśōḷa-Pallavarāyaṇ,

meaning "the chief of the Pallavas of Uttamaśōḷa."

Uttamaśōḷa and Parāntaka are titles of Cōḷa

kings and the word Pallava seems to be used in both of the titles

as an equivalent of Veḷḷāḷa, or the caste

of agriculturalists to which both of them belonged. In

the Telugu country, too, some of the Reḍḍis who belonged

to the fourth or cultivating caste, called themselves Pallava-Triṇētra

and Pallavāditya. Sir Walter Elliot has told us that Pallavarāja

is one of the thirty gōtras of the true Tamil-speaking Veḷḷāḷas

of Madura, Tanjore and Arcot. It is borne by the Cōḷa

Veḷḷāḷas inhabiting the valley of the Kāvēri,

in Tanjore, who lay claim to the first rank. All these

facts taken together seem to show that there was some sort of connection

between the cultivating caste and the Pallavas in the Tamil as well

as in the Telugu country. The available evidence is, however, not

sufficient to formulate the nature of this connection. But it may

tentatively be supposed that some of the Pallavas settled down as

cultivators soon after all traces of their sovereignty disappeared.

The other sections of the agricultural class were probably proud

of their association and considered it an honour to be looked uon

as Pallavas." (Venkayya 1907, p.242-243)

4. Iranian Origin of Dravidian Architecture and Contribution

to Dravidian Civilization

4.1. Iranic Origin of Dravidian Architecture

The Pallava foundations for Dravidian architecture is universally

accepted by scholars. For instance, a standard textbook on World Architecture

states, "Mahabalipuram, the five temples (rathas), Pallava (7th century

AD), are embryonic models of later Dravidian, or Southern, temple

styles." (Holberton, p.55). Confirming this view, the Encyclopedia

Britannica notes:

"The home of the South Indian style, sometimes called

the Dravida style, appears to be the modern state of Tamil Nadu

... The early phase, which, broadly speaking, coincided

with the political supremacy fo the Pallava dynasty (c.650-893),

is best represented by the important monuments at Mahabalipuram."

(Enc.Brit., Vol.27, p.767)

Suthanthiran summarises the views of various eminent scholars:

"The prototypes of later developed Kopurams are found

in the Pallava period. There are different views regarding the proto-types.

Heinrich Zimmer was of the view that the Pimaratam is the earliest

prototype of the Kopurams. Raghavendra Rao says that the finished

oblong plan and the two storeyed waggon roof of Kanesaratam is the

prototype of all South Indian Kopurams ... A.H.Longhurst says that

the Kailasanatha temple entrance Tavaracalai is the proto-type of

all later Kopurams." (Suthanthiran 1989, p.30)

Venkayya agrees with the Pallavite origin of Dravidian architecture:

"We now enter into a period of Pallava history

for which the records are more numerous. The facts available for

this period are definite and the chronology is not altogether a

field of conjecture and doubt. The earliest stone monuments of Southern

India belong to this period. In fact, the foundations of Dravidian

architecture were laid by the earlier kings of this series.5

(footnote 5: The monolithic caves of the Tamil country were excavated

by the Pallava king Mahēndravarman I. The rathas at

the Sevan Pagodas probably come next. The temples of Kaliēsanētha

and Vaikuṇṭha-Perumal at Kañcīpuram and

the Shore temple at the Sevan Pagodas have probably to be taken

as later developments of Pallava architecture.)" (Venkayya 1907,

p.226)

One of the gems of Pallava architecture is the Kailashanatha temple,

which was also known as Rajasimha-Pallavesvara in ancient times

(Venkayya 1907, p.234, footnote 3).

Fig.5: Stupendous Granite Kailasanatha temple (formerly

Rājasiṁhēśvara),

Tamil Nadu, view from NW, c.695-722 AD. Central shrine built by

Rājasiṁha

(Venkayya 1907, p.230). Note the Iranic vaulted-barrel cupola similar

to

Sassanian arch at Ctesiphon and the Babylonian-style step-pyramid

tower

or "Shikara". Longhurstholds that the Kailasanatha temple entrance

is the

proto-type of all later Gopurams. (Image courtesy Dr. Vandana Sinha,

American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Larger

image

The pyramid-shaped tower or Shikara of the Kailashanatha temple

is strangely similar to Babylonian step-pyramids. Babylonia was

an integral part of the Parthian empire. While such innovations

could have been due to independant innovation, it is more likely

that the Pallavas were emulating Babylonian prototypes during the

construction of Kailasanatha.

Fig.6: Pancha-ratha Pallava Temple at Mamallapuram,

Tamil Nadu. Note the Saka-Buddhist vaulted-barrell

cupola on central building.

(Image by Stewart Lane Ellington)

Larger

image

The Pancha-ratha Pallava temple at Mamallapuram consists of five

temples, one having a Saka-Buddhist cupola, one an Egyptian-style

pyramid, and three having ziggurat-shaped roofs reminiscent of Sumer

and Babylon (cf. Fig.6) . This combination of designs is unlikely

to have been independantly invented without external stimulus. These

influences could only have come via Iran and the Pallavas, for the

Parthians ruled over Assyria and Babylonia.

4.2. Spread of Buddhism

The Pallavas played a major role in propagating the religion of Buddhism.

Buddha was known as Sakya-muni, Prakrit for "Lord of the Scythians",

and was an Iranian. Thus, there is little surprise when we find Pallavas

being the most ardent propagators of Buddhism: "The sect of Buddhism

preached in China by Buddha Varman, a Pallava Prince of Kanchi came

to be known as Zen Buddhism and it spread later to Japan and other

places." (Damodaran 1980, p.70). In other words, Zen Buddhism, like

its parent faith of Buddhism, was founded by an Iranian, Buddha Varman.

4.3. Dravidian Shaivism

As noted above, the Pallavas rapidly adopted the indigenous Dravidian

religion of Shaivism, and became staunch propagators of the faith.

Scores of Shiva temples constructed by the Pallavas remain. While

the Pallavas, like the Achaemenids and Parthians, were religiously

tolerant, the devotion of some Pallava kings to Shaivism went so far

that they went to the extent of demolishing Jain temples:

"According to the Periyapurāṇam, the saint

Tirunāvukkaraśar (also called Appar), and elder contemporary

of Tiruñānasambandar, was first persecuted and subsequently

patronised by a Pallava king who is said to have demolished the

Jaina monastery at Pāṭaliputtiram and built a temple

of Śiva called Guṇadaravīccaram." (Venkayya 1907,

p.235)

By and large, however, the primordial tolerance of Dravidian Shaivism

manifested itself, absorbing the other faiths in due course of time.

5. Refutation of Rival Theories on Origin of Parthians

Ayyar has summed up the various non-Parthian theories as follows:

"Thus some scholars considered the Pallavas as of Chōḷa-Nāga

origin 2, [2. Ind.Ant. Vol. LII, pp.75-80.] indigenous

to the southern part of the Peninsula and Ceylon and having nothing

to do with Western Indian and Persia, while others placed their

original home in the Andhra country between the rivers Kṛishṇā

and Gōdāvarī; yet others connected them with the

Mahārāshṭra Āryans 3 [3. C.V.Vaidya:

History of Mediaeval India, Vol.1, p.281.] and the Imperial

Vākāṭakas 4 [4. J.B.O.R.S.,

1933, p.180ff.]" (Ayyar 1945, p.11)

We now turn to the three theories, namely Chola-Naga, Andhra and

Maharashtra Aryan origins.

5.1. Refutation of the Maharashtrian and Vakataka Origin

The surviving sculptures in Tamil Nadu depict Pallavas as tall and

dolichocephalic (long-headed) (Fig.3), while the Marathas are short-statured

and brachycephalic (round-headed). Moreover, the Pallavas were Shaivites,

as opposed to the Maharastrians, who were adherents of the Vaishnavite

religion. Further, the Pallavas waged the brutal 100-year Maratha-Tamil

war against the Maratha Chalukyas. Had the Pallavas been Maharashtrians,

it is unlikely the conflict would have been so prolonged and of such

intensity. Thus, the Pallavas were almost certainly not of Maharastrian

origin. The slight Maharastrian influence amongst Pallavas is to be

attributed to their migration through Maharashtra on their way from

Persia to Tamil Nadu.

5.2. Refutation of alleged Vedic Origin

It is sometimes asserted that the Pallavas were of Vedic origin. However,

the Vedic and Puranic evidence itself contradicts this view:

"The word Pallava is apparently the Sanskrit form

of the tribal name Pahlava or Pahṇava of the

Purāṇas. The Pahlavas are described as a northern or

north-western tribe1 (footnote 1: In chapter 9 of the

Bhīṣmaparvan of the Mahābhārata, the Pahlavas

are mentioned among the barbarians (mlēccha-jātayaḥ))

whose territory lay somewhere between the river Indus and Persia."

(Venkayya 1907, p.217)

Furthermore,

"In the Harivaṃśa 4 (footnote

4: XIV. verses 15 to 19) the Pahnavas5 (footnote 5: In

the Rāmāyana (I.55, verse 18) the Pahlavas are

said to have emanated from the bellowing of the miraculous cow Nandini,

which belonged to the sage Vasiṣṭha.) are said to have

been Kṣatriyas originally, but become degraded in later times.

They are mentioned here along with the Śakas, Yavanas and

Kāmbōjas and their chief characteristic was the beard

6 (footnote 6: The beards of the Westerns (ie. the Yavanas),

are also mentioned by Kālidāsa in his Raghuvaṁśa,

IV, 63) which Sagara permitted them to wear. In the Viṣṇu

Purāṇa , the Yavanas, Pahlavas and Kāmbhōjas

are said to have been originally Kṣatriya tribes who became

degraded by their separation from Brāhmaṇa and their

institutions.7 (footnote 7: Muir's Sanskrit Texts,

Vol.II, p.259, and Ind.Ant. Vol.IV, p.166). In Manu, the

Pahlavas are mentioned along with the Puṇḍrakas, Draviḍas,

Kāmbōjas, Yavanas, Śakas and other allied tribes.

These were all Kṣatriyas originally, but gradually became

degraded by their omission of the sacred rites and transgressing

the authority of the Brāhmaṇas." (Venkayya 1907, p.217)

Had the Pallavas been of Vedic origin, they would not be cursed

in this manner in the Brahmanic scripture. Moreover, the Pallavas

did not practice the custom of Vedic human sacrifice (purushamedha

or naramedha) and horse sacrifice (asvamedha). Nor did they permit

sati (widow-burning) or bride-burning. The Vedic and Brahmanic caste

system was also not supported. Also, the Pallavas in their earliest

times promoted Prakrit and not Sanskrit. Thus Venkayya notes, "The

earliest known records of the Pallavas are three Prākṛt

copper-plate charters, viz. (1) the Mayidavōlu plates of Śivaskandavarman,

(2) the Hirehaḍagalli plates of the same king and (3) the

British Museum plates of Cārudēvi." (Venkayya 1907,

p.222) These facts disprove the Vedic origin of the Pallavas.

5.3. Refutation of the Dravidian Origin

That the Pallavas were not Dravidians is evidenced from the fact that

their migration can be clearly traced via copper-plate grants as being

from the Telugu to the Tamil country. The Pallavas initially promoted

Prakrit, which also goes against the proposed Andhra origin of Pallavas.

Had they been Andhras, they would no doubt have propagated the proto-Telugu

Dravidian dialect.

In further opposition to the Dravidian origin of Pallavas, Venkayya

has fittingly asked why the Andhras should have adopted a name which

would lead to them being confused with the Pahlavas of Persia.

"Why the indigenous tribe which was formed in the Gōdāvari

delta called itself Pallava, a name which would lead to their being

mistaken for being Palhavas of Western India is a question which,

to my mind, must be satisfactorily answered before the theory of

indigenous origin can be accepted." (Venkayya 1907, p.219, footnote

5)

However, the Pallavas rapidly adopted the indigenous Dravidian

religion of Shaivism and propagated it, just as the Germanist Lombards

accepted the Roman Catholicism of their Latin Italian subjects.

That the Pallavas were able to flourish in Dravidia is a testimony

to Dravidian tolerance and open-mindedness, a rare characteristic

in those days.

The remaining rival theories on the origins of the Pallavas having

been undermined, the Parthian origin of the Pallavas remains as

the sole logical alternative.

6. Consequences and Conclusion

The Parthian origin of the Pallavas was eagerly adopted by virtually

all schools of Dravidologists from the very beginning. Formerly,

Indo-European influence in Dravidian had been attributed solely

to Sanskrit. Anti-Sanskrit Dravidianists welcomed the Iranic origin

of Pallavas as it decreased the Sanskrit proportion in the Indo-European

component of Dravidian civilization. Indeed, certain votaries of

this school believe that Iranic influence in Dravidian is more important

than that of Sanskrit.

Dravidianist evangelists have in their turn used the Pallava example

to demand that the Tamil Brahmins adopt Dravidian culture. Their

chief argument is that, if the Pallavas from distant Persia could

so eagerly adopt Dravidian civilization, then why couldn't the local

Tamil Brahmins?

Multi-culturalist Dravidianists, meanwhile, upheld the Pallavas

as an example of ancient Dravidian tolerance and multi-culturalism.

The South Indian Brahminist school, which is also largely multi-culturalist

(often miscalled 'secularist') in character, has largely followed

this path as well. The political use - and abuse - of history goes

on.

The Parthian origin of Pallavas also provides an explanation for

the presence of tall, fair-skinned members of non-Brahmin castes

in Tamil Nadu and other Dravidian states. Formerly attacked as mixed-caste,

part-Brahmin, offspring, it is observed that such persons are at

present claiming a Pallava-Parthian origin instead. This is certainly

true of certain Cholas, Vellalas and Reddis. Especially in case

of those fair individuals who are long-headed, a Pallavite origin

is more plausible than a mixed-Brahmin one, for the South Indian

Brahmins are generally round-heads. The Parthian theory of the origin

of Pallavas has thus helped a large number of people to be rehabilitated

in Dravidian society.

It is hoped that Iranists will be inspired by this work to carry

out further research on the achievements of the enterprising Pallavas

in Dravidia, and bring to light the full scale of Iranic influence

in Dravidian civilization.

Author

Afsar Abbas is a professor at the Institute of Physics, Bhubaneshwar,

India

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof. Shireen Moosvi and Prof.

Irfan Habib (Aligarh) for their kind assistance with references.

The author is also very grateful to Prof. P. Oktor Skjærvø

and Prof. Michael Witzel (Harvard) for kindly sending important

research material. Many thanks to Fatema Soudavar Farmanfarmaian

for fruitful discussions, and to The Iranian for publishing this

paper.

The author gratefully thanks Michael D. Gunther, //www.art-and-archaeology.com;

Dr. Vandana Sinha, American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon,

//www.indiastudies.org; and Stewart Lane Ellington, //stewellington.com

for permission to reproduce their wonderful images in this paper.

References

Ayyar 1945: "A New Link between the Indo-Parthians and the

Pallavas of Kanchi" by V. Venkatasubba Ayyar, Ootacamund, Journal

of Indian History, Vol.XXIV, Parts 1 & 2 (April & August 1945) Serial

Nos. 70 & 71, p.11-16; Ananda Press, Madras.

Damodaran 1980: "Contribution of the Tamils to World Culture",

G.R.Damodaran, J.Tamil Studies, vol.18 (Dec. 1980) pp.69-76.

Derakhshani 1999: "Die Arier in den nah‘stlichen Quellen des

3. und 2. Jahrtausends v.Chr." by Jahanshah Derakhshani, International

Publications of Iranian Studies, 2.Auflage, 1999; ISBN 964-90368-6-5,

EUR 20,00.

Holberton 19??: "The World of Architecture" Paul Holberton,

WHSmith, Michael Beazley Publishers, 14-15 Manette St, London W1V

5LB.

Minakshi 1977: "Administration and Social Life under the Pallavas",

by Dr. G.Minakshi, University of Madras, Madras, 1977, Rs. 27.

Nair 1977: "The Problem of Dravidian Origins - A Linguistic,

Anthropological and Archaeological Approach", by T.Balakrishnan

Nair, University of Madras, Madras, 1977.

Skjærvø 1995: "The Avesta as source for the early

history of the Iranians", P.Oktor Skjærvø, in `The

Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia', ed. George Erdosy, Walter

de Gruyter, Berlin 1995, pp.155-176.

Spooner 1915: "The Zoroastrian Period of Indian History"

by D.B.Spooner, J.of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain

and Ireland, 1915, p.64-89 (Pt.I); p.405-455 (Pt.II).

Suthanthiran 1989: "Evolution of Gopura in Temple Architecture

of Tamil Nadu", by A. Veluswamy Suthanthiran, J.Tamil Studies,

vol.35 (June 1989) pp.28-38.

Venkayya 1907: "Annual Report 1906-7", Archaeological Survey

of India, "The Pallavas", by V.Venkayya, p.217-243; reprint

Swati Publications, Delhi.

Waddell 1929: "The Makers of Civilization in Race and History",

by L.A. Waddell, 1929, reprint S.Chand & Company, New Delhi, 1986.

Witzel 2001: "Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian

and Iranian Texts," by Michael Witzel, El.J. of Vedic Studies

7-3 (2001), p.1-115.

* Send

this page to your friends

* Printer

friendly

|