Heap of dust it is not Heap of dust it is not

Sialk is just one of thousands of structures

of antiquity in Iran plundered by colonialists,

thieves, incompetent

authorities, and time itself

By Nima Kasraie

April 20, 2004

iranian.com

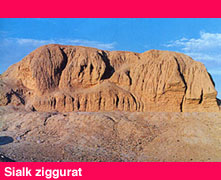

Upon visiting the oldest ziggurat in the world, one

is only greeted with the solitary sound of dusty wind gusts. Here,

tucked away in the suburbs of Kashan,

sits the 7,500-year-old ziggurat of Sialk, a testament to ancient civilizations

that flourished in Iran long before the Egyptian or Greek cultures blossomed.

Like many other ruins in Iran, unfortunately, what is left of this per ancient

edifice is only a big pile of crumbling bricks.

This author is familiar with the

efforts of dozens of historic preservation institutions as well

as local, state, and federal organizations

in Knoxville, that preserve and protect the heritage of eastern

Tennessee. These institutions

will do what it takes to make sure that a humble house built in the 1920s will

receive historic overlay zoning and come under he protection of the law.

In Sialk, on the other hand, what we see is a sign

saying: "Please do not touch objects", and next to it another

sign saying: "Items excavated here belong to the Stone Age". When

the guard, sitting in a chair, isn't looking, you can easily lift the rope

where the signs hang, and sneak a few pieces of millennia old ceramics,

spear

heads, or other items into your pocket.

The guard won't care if you climb

on top of the crumbling ziggurat itself, and while walking behind the ziggurat

you

can enjoy how it feels to kick 7000-year-old mud bricks to rubble.

You can even ask the guard to let you see the "off limit" 5,500

year old skeletons unearthed at the foot of the ziggurat. The guard won't care if you climb

on top of the crumbling ziggurat itself, and while walking behind the ziggurat

you

can enjoy how it feels to kick 7000-year-old mud bricks to rubble.

You can even ask the guard to let you see the "off limit" 5,500

year old skeletons unearthed at the foot of the ziggurat.

Built by the Elamite civilization, Teppe Sialk was first excavated by a team

of European archeologists in the 1930s. Like the thousands of other Iranian

historical ruins, the treasures excavated here eventually found their way

to museums such

as the Louvre, the British Museum, the

New York Metropolitan Museum, and private collectors -- including the

three jars you see in this piece.

What little is

left of the two Sialk ziggurats is now threatened by the encroaching

suburbs. It is not uncommon to see kids playing soccer

amid the

ruins.

One cannot help but imagine that if Sialk were located

in Tennessee,

the ziggurat would have been fully preserved by three layers of vacuum-sealed

Mission Impossible-type weathering protection systems,

if not rebuilt and

restored

altogether like the cathedrals in Europe. Hollywood would have made several

movies, using the monument as a device to further publicize the

antiquity and sophistication

of Western civilization. One cannot help but imagine that if Sialk were located

in Tennessee,

the ziggurat would have been fully preserved by three layers of vacuum-sealed

Mission Impossible-type weathering protection systems,

if not rebuilt and

restored

altogether like the cathedrals in Europe. Hollywood would have made several

movies, using the monument as a device to further publicize the

antiquity and sophistication

of Western civilization.

The significance of the scientific and cultural achievements

of the Elamites and their influence on other civilizations can

be better understood when

we learn that according to some scholars the first wheeled pitcher (or

wheeled roller)

is known to have been invented by the Elamites.

Furthermore, the first

arched roof and its covering, which are very important techniques in

architecture were invented by the Elamites, and used in the mausoleum

of Tepti-ahar

around

1360

B.C. (unearthed in the excavations made at Haft Tappeh) nearly 1,500

years before such arches were used by the Romans. Furthermore, the first

arched roof and its covering, which are very important techniques in

architecture were invented by the Elamites, and used in the mausoleum

of Tepti-ahar

around

1360

B.C. (unearthed in the excavations made at Haft Tappeh) nearly 1,500

years before such arches were used by the Romans.

But the painful

reality is that Sialk is just one of thousands of structures

of antiquity in Iran plundered by colonialists,

thieves, incompetent

authorities, and time itself. Only the more famous ones

come to attention

when threatened, and a select few come under the protection of UNESCO.

Other

ancient structures of Persian heritage are not so lucky. The

Sialk ziggurat at least has a guard or two protecting it, and Cultural

Heritage Organization

(hopefully) pays for the rope that supposedly prevents visitors

from

stealing the numerous excavated pieces. Others like the massive

Sasani-era citadel of Nareen Ghal'eh (See photo)

in Naeen have turned into

a garbage

dump by the locals. And many many others fare even worse than that.

Protecting

such heritage is a critical responsibility for everyone. Sometimes

I feel ashamed when I hear about Italian or Japanese authorities

voicing concern

over the

preservation of buildings in Iran. What are we doing? Turning ancient

caravansarais into bus

repair garages for TBT and IranPeyma?

If there is one reason why

Persian culture has managed to survive thousands of years of

change and onslaught, it is because of the

vast inheritance

that we

are now so easily giving away. The destruction of our monuments

from Taq-I-Kasra near Baghdad to the tombs of Bukhara and Samarqand

are

only minor facets of

this tragedy.

The least we can do here in America, is document

our culture by publishing

articles, making websites, creating databases of information,

photographs, and the fine arts, and spread the word around

by calling for the

help of other fellow

Americans of Iranian heritage.

Author

Nima Kasraie is a graduate student in Physics at

the University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

.................... Say

goodbye to spam!

*

*

|