|

|

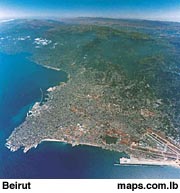

Beleaguered beautiful Beirut December 3, 2001 Israel never lets you forget you are in Beirut, "the only Arab capital occupied by Israel." They "buzz" the city quite frequently. "Buzzing" is a rather innocuous term for flying over the city (and the liberated South) in their fabulously beautiful and deadly fighter-jets at supersonic speed, and breaking the sound barrier with the sound of a clearly audible but dull explosion... The first time it happens is the day after my arrival. I am in some shop buying a mobile phone (and that is another story to be told) and my new flatmate, a German researcher and journalist, tells me with a gleeful and mischievous gleam in his eyes that the BOOM we just heard are "The Israelis". To be totally honest, I am a bit exhilarated and not in the least bit apprehensive.

But the blackouts happen often, reminding me of the post-revolution, war years in Iran, when we were used to lighting candles, fanooses and Aladdin lamps... and here, too, a few times I have had to climb the eleven floors to get to our flat, and one time, when in dire need of a shower during the blackout, I actually boiled water over the gas stove and took a bucket/sponge bath. Definitely reminded me of Iran. The state of public utilities in Beirut is quite awful, which explains my (very reluctant) purchase of a mobile phone: land lines are hard to come by, they are expensive and difficult to install, and almost all the middle and upper classes (except for the poor of course who can't afford the fairly expensive rates) have cellphones. And generators, which explains why there isn't much public pressure (at least by the middle classes) for the government to fix the electricity supply. When the city lights go out in a neighborhood, the hum of the generators begins. Not as much in our neighborhood, which is a middle class neighborhood tending towards the lower and more or less Shi'a. Here, the neighborhoods are somewhat divided by religion, and the largely Muslim West Beirut (which was so mercilessly laid under siege, shelled and attacked by Israel and Phalangist forces during the Civil War) is separated from the largely Christian (and more affluent) East Beirut, by the infamous Green Line, Dameshgh Street, which is still marked by hollow pocked dark buildings that look corroded, eaten away, poxed by bullet holes and mortar. I am here in Beirut to do my PhD dissertation research and also a bit of volunteer work with Palestinian refugees. The dead Europeans in this city live better than the living refugees. My neighborhood is the neighborhood of graveyards: a vast Sunni graveyard right next door with beautiful gray-white marble gravestones all neatly in a row for an entire vast city block, and then behind that graveyard, and behind our apartment building are the English and French military cemeteries: the graves of the colonial soldiers who fell to the various wars of conquest in the region. In fact, some of the French dead seem to be of Arab or perhaps Senegalese (I have been told) descent (one can tell by the sound of their names and the crescent on their graves), and there are other French- and Englishmen with their European names, and all were apparently killed during the suppression of the nationalist Syrian revolt of 1925. And behind them -- also shaded by cypresses and plane trees -- is the serene and beautiful graveyard of the Polish Refugees (I have yet to find out when and why they came here) -- often locked, but with fresh flowers and burning candles on a few graves every so often. And behind them and slightly to the South are several garbage dumps that smell of vomit, death and the uncollected debris of god knows how many years, and immediately behind them are Sabra and Shattila refugee camps. I am not certain that a "refugee camp" is a very descriptive phrase for what these places are (I have so far visited Sabra and Shattila, Mar Elias, Burj-al-Barajneh, all here in the southern suburbs of Beirut, and Nahr-el-Bared in the suburbs of Tripoli to the north). A sort of solid shantytown is more like it. In Iran, the shanty-towns south of Tehran used to be built with discarded tin cans and corrugated zinc roofs and here, they are in cement breeze-block, white-washed (as if the inhabitants really want to honor their environment as best as they can). These camps have been around for upwards of fifty years now and they don't look fragile, but they do look poor. Additionally, more than anywhere else in Nahr-el-Bared, but also in Burj, there are metal skeleton extensions sticking out from the roofs of the houses, and despite the fact that the Lebanese government has prohibited any construction in the camps, when families grow, additional fragile floors are added to the already burdened buildings and the camp grows upwards, since the outer boundaries are so heavily circumscribed. In the camps, exposed water and sewage pipes run all over the place; they often break down from the foot traffic traversing them and one has to duck to get away from whatever it may be pouring from the broken pipes. The electricity is taken -- not always legally -- from a wild tangle of wires coming off the electric poles and once the Lebanese government figured out that they can't stop it, they began charging a flat rate for each house for all services. Power goes out all the time (but it does in Lebanese neighborhoods also) and the sewers are not the best. When I was in Nahr-el-Bared, it rained torrentially and the sewers flooded and the streets were veritable rivers. Speaking of the streets, they are amazingly narrow little alleys. Two people can only walk shoulder to shoulder in these alleys if one of them is a child or a very slender person. The degree to which the alleys are kept clean differs. Nahr-el-bared was quite nice, and the parts of Burj-al-Barajneh which I have seen were also quite tidy. Sabra and Shattila are a different story though. Sabra and Shattila's alleys are filled with all sorts of rotting garbage, and in the demarcating line that separates them, there are vast hulks of buildings standing unrepaired, poxed with bullets and riven with vast holes (from mortar fire), from the Israeli/Phalange attacks on the camps in 1982, but also from the War of the Camps in late 1980s which pitted Amal against the Palestinians and which -- so far -- has been the memory I have heard spoken about most openly. This is perhaps because the Phalange culprits of the 1982 massacres are in positions of great power, untouched and untouchable, and with the ability to make these people's lives hell. Or perhaps because most of the people in the camps who have spoken to me of the War of the Camps -- knowing that I come from an Iranian Shi'a background -- are testing me and my political positions. I am still figuring this one out. Being Iranian here -- in both Palestinian and Lebanese circles -- has been wonderful. People love the Iranians here, and in fact, I have met a number of people who are of Iranian descent (but who are now totally Lebanised): the newspaper seller from whom I buy Al-Nahar everyday told me today that his mother is from Tabriz (and her last name is Tehran-zadeh) and I met a really brilliant filmmaker (whose piety is definitely not as "seft-o-mohkam" as one would expect, but who works for Hizbullah's al-Manar TV) whose grandfather was Iranian and he still has his Iranian passport, though he doesn't speak a word of Farsi and has never been to Iran. The Palestinian community -- who has no rights here in Lebanon: no right to work, own property, or pass on already-owned property to their children -- is served by a network of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), who try to help out as best they can. My interaction with the various NGOs which serve the community in various capacities has been pretty interesting. I have been interviewing the guy who runs Arab Resource Center for Popular Arts; this NGO does the kind of work that will probably end up featuring in my dissertation: collective memory collections; recordings of those cultural aspects of life which essentially act as defining the Palestinian people as a cohesive national group with its own cultural traditions. They collect oral histories, folk songs, tales, and all sorts of other subtle and delicate things that make a group of human beings a "people" with a shared understanding and view of the world. I have also been doing some volunteer work at the Children's Center at Sabra and Shattila, where I spend a couple of afternoons every week tutoring kids with their English and their homework. Looking at the books that the UNRWA (the UN organization taking care of Palestinian refugees) and Lebanese government provide makes me want to pull my hair out. These books are atrocious beyond belief.The 5th grade English lessons are about kids going to a park somewhere and riding a ferris wheel and fun houses and bumper cars. As if knowing what the hell a ferris wheel is helps a kid living in camp with learning English in any way at all. And the 9th grade English book has a passage about the Olympics (the OLYMPICS for god's sake for children who don't have a playground to play football on) which contains precious lines like, "The Olympics are a place where people -- rich or poor -- come together..." and asks "Do you agree with the statement that 'Sports are not about fair play, but about sadistic pleasure, a war without shooting'?" It is almost embarrassing to hear these words in English. The books are put out by the Lebanese Ministry of Education and purchased by UNRWA and god knows, I just wanted to cry -- aside from their absurdities, sheer irrelevance, and perhaps willful depoliticization of all topics -- they are full of grammatical, punctuation, and spelling errors. UNRWA also does not provide history lessons for these kids. And Pascale (a Lebanese friend) tells me that in school they learned only about French history, and that she knows very little about Lebanese history. So it really isn't limited to Palestinians, but you would think that a dispossessed people are entitled to THEIR history, to knowing what happened to them, where they came from and how it is that they ended up in the right-less, hopeless, poverty-infested camps that they live in. But the education is not the only thing suppressing their memories and their political independence through the use of the awful bare-bones curricula; an activist/volunteer Lebanese woman (a human of a rare breed) who is about 25 and who for the last 5 years has been working 2-4 hours a day as a volunteer with these kids told me recently that for a whole week, she had been running around on behalf of a kid who was kicked out of a school for good (he is 14), because he dared defy the authority of the principal when the principal wanted to beat him with a stick for laughing in class. Meyssoun (this woman) has been running around from UNRWA office to school back to UNRWA office trying to get the kid re-admitted, but no one really cared. It wasn't until she threatened to write to the New York office of UNRWA, that they relented and took the kid back. But the principal apparently promised to make his life hell. It is as if the children are trained to be some sort of obedient little automatons, and even the UN education system that is set up to support them essentially screws them over. Some of the NGOs try to offset the incredible weaknesses of UNRWA by offering tutorials, historical materials, and additional remedial classes, but it is like trying to put one's finger in the crack of a dam! I have also been working with yet another human of rare breed, an activist Palestinian woman, by the name of Olfat, who has her own NGO serving the women of Burj-al-Barajneh camp. She was originally trained as a nurse and lived through both the Sabra and Shattila massacres (she managed to be one of a handful of people who escaped the Shattila hospital through a window while the Phalange were massacring all the Palestinian nurses and doctors) and she lived through the siege of the Burj al Barajneh camp under Amal. The images of the siege are searing: I have been to houses in the camp where huge holes in walls and ceilings still attest to the damage done by mortar fire, and I am told stories of so many people having lost friend and family in these unnecessary and brutal conflicts. When under siege, Olfat was the only medic in a polyclinic with no equipment, or drugs, or help -- and she said that on one hand she was performing minor surgery, pulling bullets and shrapnel out of people without any anesthetics and on the other hand, the seriously injured people (men, women and children hit by mortars, shrapnel and bullets who could be saved if they could be moved into a proper hospital) were left in a room to die, since there was nothing that could be done. This experience left her with little desire to work as a nurse and so a couple of years on, she set up her organization that not only gives the camp people vocational training, literacy classes, tutorials for kids, and health and wellness workshops, she also sets up classes for women, telling them about their legal rights, and their human rights as women and as Palestinian refugees. She gets huge amounts of respect in the camp and outside it from everyone, and being the gentle and fabulous feminist that she is, she is a joy and a wonder to be around. She will probably be the one that will end up setting me up in an apartment in the Burj camp in January so that I can be closer to the community I am working with. As I write this, the streetlights of the city of Beirut and its suburbs in the distant hills are coming on and the sunset azan is being sung in the mosque right down the street (the azan here sounds a lot like the azan in Iran -- I have discovered that Muslim countries, all have their own azans, with different rhythms and different cadences -- and Beirut azans take me back to those dusky evenings of Mashhad). This is a beautiful city -- and an amazing country. And an amazingly small one: 4-5 million people in the whole of a country which can be traversed in a fast car from tip to tip in 4-5 hours, with exquisite views of the sea, beautiful greenery, and lovely people who seem to desperately intent on forgetting the long and brutal Civil War which took hundreds of thousands of lives, displaced a third of the population, and permanently scarred a lovely and open people. There are no hands, no sides, no groups not bloodied in some way, and that may be why people want to forget. There are still lots of buildings with marks of war (including the building I live in which has bullet holes lodged in the walls and the metal window frames) but since the end of the civil war, there have been more buildings destroyed in the name of "reconstruction" than during the war itself. The center of Beirut is this gleaming beautiful Mediterranean set of stone arcades with gorgeous arches and promenades, the buildings glowing with their luminous creamy yellow limestone -- but the center of the city is somewhat plastic, a bit dead, perhaps still coming back to life, whereas the other neighborhoods are more alive. My neighborhood is a veritable beehive of activity: shops and people and vendors and cars and cars and cars and cars all lying here somewhere in the middle between the hills in the east that glow at night like bejeweled skies, and the blue blue blue Mediterranean in the west that gleams in the sunlight. There are more Shi'a neighborhoods further to the south than where we live (we are just inside the borders of the city proper, the Shi'as who are demographically the most numerous and the poorest religious group here live outside the city proper). In these neighborhoods, one can see the occasional hagiographic portraits of Khomeini, Sheikh Nasrallah (the military commander of Hizbullah) and even an occasional Khamenei, even if the political positions of Hizbullah are much closer to Khatami's reformist stance. Hizbullah is not quite like the image portrayed by most American media outlets. On the one hand, its social/political wing is remarkably organized, efficient, uncorrupt (which is something quite admirable and rare in this country, apparently), and quite amazing in providing services and support for their constituency (the Shi'a poor in this country). They have a women's organization which provides micro credit loans, services, classes, and social welfare to women and children, and their military wing is nationally recognized (even by the right-wing new Phalange party) as the liberators of southern Lebanon from Israeli occupation. On the other hand, friends who are doing (sympathetic) research about the women's programs of the Hizbullah tell me that within the party itself, there are all sorts of factions and fractionalization -- and that the women constantly fight to get their share of the budgetary allocations and that the women are far more feminist, and far more independent than the men in power in Hizbullah like them or publicly allow them to be.In fact, this kind of complication and complexity, which certainly does not lend itself to the simplifications we are accustomed to hearing, is present in every political and religious group here in Lebanon. For example, a general consensus among scholars and activists is that the poor Shi'a women in Lebanon -- despite the socioeconomic limits placed on their activities and education -- are in fact the most independent of all women; even if unlike their Maronite sisters, they wear the hijab. They have their own businesses (sometimes ingeniously hidden from their husbands), they are politically active, and they are also politically aware and curious. As for my visceral reaction to this country and especially to this city: I love it. It is amazing. It is wonderful, gaudy, polluted, beautiful, disgusting, consumerist, superficial, crowded, expensive ($7 glasses of beers in pubs are NOT an oddity), and absolutely incredibly seductive. It is beautiful and complicated (I don't know how a tiny tiny tiny country with such a small population can get as complicated as this -- but it is), and the food (all the thyme and olive and tomatoes) and the wine are amazing; the intellectuals are actually interesting and the young ones who profess a kind of hipster cynicism are in fact sweetly optimistic in that Sartre-like existential sort of way. An old Palestinian revolutionary I recently interviewed said that Lebanon, tiny beleaguered beautiful Lebanon, is a mirror of everything that happens in the Middle East. I couldn't agree more: problems with Israel, with refugees, human rights, women's rights, Shi'a radicalism, Sunni radicalism, unfettered globalization, unfettered real estate development encroaching upon gorgeous green lands, confessionalism, civil war, colonialism, occupation... you name it, the country has seen it and yet, it remains an amazing place to be: inviting, tempting, complicated and brilliant... And that is despite the frequent sonic booms set off by the invading Israeli jets who cruise overhead all the time and despite the economic downturn, and despite the pressures on the economy and politics of this country by the U.S. with its stupid extraterritorial terrorism laws (which in fact accomplish nothing except impoverish the poor who desperately need and receive the services of those banned "terrorist" groups)... When in the mornings sunlight pours through my window and I wake up looking at the hills in the distance, I am filled with wonder and astonishment at my good fortune. Beirut is like a woman -- this is not an original thought of mine, many others have said so -- she is wise and beautiful and ravaged by age and cruelty, she is complicated, cannot be summarized in two representative sentences; she is so strong, so overwhelming that one comes to either love it or hate it, no in-between emotions are allowed. And it is no wonder that Mahmoud Darwish, the great Palestinian poet has written:

|

|

|

Web design by BTC Consultants

Internet server Global Publishing Group

Well, that is a lie; I am just

the tiniest bit apprehensive. After all, only two years ago, Israel bombed

the major electrical facilities of Beirut, plunging the city into a 12 hour

blackout which is remembered not without some sort of strange fondness by

my flatmate, who has lived here for three years and must have had to go

up and down the eleven floors of our apartment to get to the flat on foot...

Well, that is a lie; I am just

the tiniest bit apprehensive. After all, only two years ago, Israel bombed

the major electrical facilities of Beirut, plunging the city into a 12 hour

blackout which is remembered not without some sort of strange fondness by

my flatmate, who has lived here for three years and must have had to go

up and down the eleven floors of our apartment to get to the flat on foot...