The artist and the craftsman The artist and the craftsman

Post-revolutionary Iranian classical music

Susanne Kamalieh

May 19, 2005

iranian.com

McLEAN, VIRGINIA -- With all due respect to Dr. Nafisi,

I beg to differ with him on the subject of Iranian music in general

and

his article -- "The

crisis of Persian culture" -- about the Kennedy Center

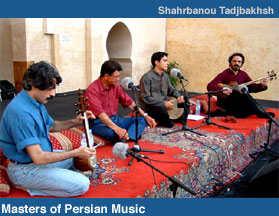

concert "Masters of Persian Music" in particular, although it seems

to

reflect the sentiments of many in the audience.

On the evening of March 5th the huge Kennedy Center

Concert Hall was more or less packed. For many attendants

the concert had social as well as artistic significance. The Iranian

community was extremely excited about having their concert in an

establishment of such caliber. The Kennedy Center is undoubtedly

one of the most, if not the most, -- important cultural symbol

in the nation‚s capital. "Making it" to the Kennedy

Center in Washington has the same significance as "making

it" to the Carnegie Hall, which is the ultimate sign

of success in live performance. So, for the Iranian community seeing

their most cherished musicians perform in the great halls

of American high culture was almost triumphant.

Sadly though, the venerated Kennedy Center Concert Hall does

not lend itself well, acoustically or otherwise, to a Persian

quartet. The small ensemble would have sounded much better

in a chamber orchestra setting rather than a concert hall that

is primarily designed for a symphonic orchestra. The Persian

instruments did not amplify well, but more importantly, the

necessary atmosphere that is only created in an intimate setting,

where the artist and his audience connect and interact, and is

conducive

to improvisational music, did not exist in the large space

of a concert hall.

The Persian audience was extremely enthusiastic

and supportive of their music heroes, but there was no proximity

for the musicians to feel that warmth and to respond to it. Thus

the concert was only a great performance because of the enormous

talent of the artists, and not an inspired one. For an audience

with such extremely high expectations that could be a disappointment.

My main dispute with Rasool Nafisi, however, is on his condemnation

of contemporary Persian music. Although, I don't consider

myself an expert in the technical aspects of Iranian musical

traditions, as a native Iranian, and a music lover, I have a totally

different experience with regard to the development of music

in Iran after the Islamic revolution.

I was living in Iran 25 years ago when the revolution broke out.

I remember how those of us involved in artistic activities

were searching hard for venues to express our emotions, pro

or anti-revolutionary, through our artwork -- most of us quite

unsuccessfully. Changes were happening at a staggering pace,

and there had not been enough time to digest, absorb and

to give back. Nevertheless, we certainly felt the need for artistic

expression of our intensified feelings. And that was when,

more than any other art form, music came to the rescue.

At

the time, when Islamic law was prohibiting musical activities altogether

calling it "haram", many traditional musicians

responded by producing music that was immediate to the revolutionary

fervor of the people, reflective of the political and social energy,

and irresistible even to the Islamic Republic. So it defied, it

endured, it resisted, and it flourished into what Dr. Nafisi is

calling "impoverishment of the traditional form." On

the contrary, I find this to be in the best tradition of artistic

evolution, and a genuine artistic response to the need for formalizing

contemporary "human

emotion."

I grew up listening to Marzieh, Delkash, Banan, the great

"Golha" programs and other traditional music and

I enjoyed it very much. But let's face it: the pre-revolutionary

music won't

make it in today's Iran. Try listening to it; other than

some nostalgic value, it sounds old and out of place.

To appreciate contemporary art one MUST make oneself open to

the experience with active participation and let go of dogmatic

tendencies that restrain our enjoyment -- even then it

may take some effort to truly appreciate something totally new.

It is much easier to relate to what we are accustomed to.

The old format becomes a religious doctrine, an untouchable

and unreceptive part of one's belief system. Changing it

threatens some deeply ingrained rules and regulations that

seem essential. To appreciate contemporary art one MUST make oneself open to

the experience with active participation and let go of dogmatic

tendencies that restrain our enjoyment -- even then it

may take some effort to truly appreciate something totally new.

It is much easier to relate to what we are accustomed to.

The old format becomes a religious doctrine, an untouchable

and unreceptive part of one's belief system. Changing it

threatens some deeply ingrained rules and regulations that

seem essential.

Throughout history art has faced this attitude. It has always

been the dilemma of the artist: to stay within the established

rules and enjoy the recognition, fame, and praise of his

contemporaries or follow his artistic instincts at the risk of

moving beyond the realm of public appreciation.

Let's

not forget that Stravinsky was booed on the opening night of the

Rite of Spring. Beethoven was considered to be losing his mind

when composing his Ninth Symphony. Van Gogh did not sell

a single work during his lifetime. The instances are frequent

and common rather that rare and noteworthy, far too many to mention.

Great advances in art, however, have always come about through

incessant probing of boundaries and the breaking of rules

and traditions.

The innovations that Shajarian and others bring to Persian music

are hard to get used to for those of us who have enjoyed Golha

for a large part of our lives. But it would be a crying shame

to miss the enormous energy and the new vitality that we find in

the post-revolutionary Iranian music.

What Dr. Nafisi calls

the "hurried tone" of Alizadeh might be the force

and the power that challenged religious dogmas of the government

and brought about the fatwa that kept music alive

in the country. (Mohamad Reza Lotfi and the Chavosh Group

also come to mind.) The old Golha music would have

been squished under the wheels of the Morality Police's

four-wheel-drives before getting a chance to make a sound.

It wouldn't have had the strength or the stamina to survive

the revolution and it did not.

It is also note-worthy that some of these innovations are extremely

creative and clever ways of overcoming the censorship and

limitations that have been imposed by the government. The

asynchronous duets are being used to allow women to sing in public

in spite of the ban on female voice. Performances of great

musical plays that are very popular in Iran today are taking

full advantage of it and bringing great female singers to the

stages of Iranian theatres.

The achievements of these musicians are admirable. Unlike most

of us they did not run away from hardship. They stayed and

used their talents and creativity to produce a new art form,

and more importantly, a voice for a population that needs it badly.

Iranians inside the country or abroad recognize that and

appreciate it deeply. The achievements of these musicians are admirable. Unlike most

of us they did not run away from hardship. They stayed and

used their talents and creativity to produce a new art form,

and more importantly, a voice for a population that needs it badly.

Iranians inside the country or abroad recognize that and

appreciate it deeply.

In his article Dr. Nafisi talks about "honar", meaning

art, versus "technique".

He states that the Iranian musicians, by putting emphasis

on their technical skills, never make the transition to being

an artist and stay at the level of a great technical expert. I

believe the painstaking perfection of one's craft is

what allows the true metamorphosis. The transition will not

come from a conscious decision to stop being a craftsman and start

being an artist.

You become an artist and express feelings, emotions,

make statements, or do whatever it is that artists do, as

you overcome the technical difficulties of your instrument.

When you don't spend your energy constructing sentences,

then you start talking, and the rest has to do with what

you've got to say!

It is not an easy task to define art, to tell art from non-art,

or to distinguish good art from bad art. Anybody can sign

a piece of junk and call it art (no disrespect to Marcel Duchamp!)

But to call Shajarian's music anything but high art would

be a wasted effort.

|