Blood-less coup Blood-less coup

New-conservatives, regime crisis and political perspectives

in Iran

Ardeshir

Mehrdad and Mehdi

Kia

August 16, 2005

iranian.com

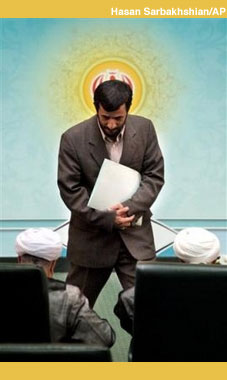

In the recent presidential elections

in Iran, Mahmood Ahmadinejad, an unknown conservative military

commander, won. His victory

was surprising, as many had predicted Hashemi Rafsanjani

would become Iran's next president. Rafsanjani, perhaps

the second most powerful man in the Islamic Republic, was

supported by a broad coalition of reformists and pragmatist

elites. The shock of this surprise victory may partly explain

the crude nature of some of the analyses that followed.

Even more striking is the failure to address the deeper

causes

and background to this event, and to analyse its consequences.

This article is an effort to address these issues. At the

onset a few observations may be helpful:

Background

In the Islamic Republic, elections, including

presidential ones, are fundamentally undemocratic, tightly controlled

processes. The law deprives many citizens such as women,

religious minorities (including non-Shi'ite Muslims)

and political opponents of the religious state, etc from

standing for president. This is enforced in practice by the

unlimited power of the Council of Guardians [1].

This Council

has consistently rejected anyone it considers unsuitable

for the ruling circles. Therefore, in practice, elections

in the Islamic Republic are nothing more than a "beiat" [expression

of allegiance] with one of the few, and often the only, person

the Council of Guardians has let through its net [2]. In

such conditions non-participation in elections, rather than

reflecting voter apathy, is one form of expressing "dissent",

a means of protesting against the regime and questioning

its legitimacy [3].

Those sections of the state that are up for periodic elections,

including the presidency, are in general of secondary importance

in the power structure. The system revolves round an unelected

central core, headed by a Supreme Leader, vali-e- faqih,

with truly unlimited powers. It is here that all major decisions

are made, especially so after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini

and his replacement with Ayatollah Khamenei. The presidency

and the administration have ultimately an executive responsibility

-- or as the outgoing President Mohammad Khatami puts it they "play

the role of a footman".

Yet because of the faction-ridden

nature of the ruling elites, the individual in charge of

the executive becomes important since this appointment

could effect the distribution of public resources and to some

extend

the ability of the entire state structure to function.

Hence control of elected organs, and the presidency in particular,

are also hotly contested, and subject to intense bargaining,

among the various factions.

The most important function of elections in the Islamic

Republic rests precisely here: namely the redistribution

of power among the various ruling factions. This contest

is particularly acute at times when the internal crisis of

the regime is intensified and when the normal bargaining

processes are unable to reach a "consensus". "Elections" in

such conditions become a mechanism for the re-allocation

of power, where factions test their respective power against

electoral legitimacy.

Until the latest election, the normal

practice in the Islamic Republic was for all the factions

to observe the rules of an in-house democratic game. After

the initial weeding process by the Council of Guardians,

the power centres did not intervene in favour of one or other

candidate outside "the legal framework", or more

accurately, did not undermine too explicitly legal appearances

[4].

What at first glance distinguishes the latest election

in the Islamic Republic from all its predecessors is that

for the first time the rules of the democratic game among

the regime's various factions have been openly flouted.

Cheating, in the shape of manufacturing votes has always

been a common practice, whether through stuffing ballot

boxes, or miscounting this or that voting booth in favour of a

candidate.

The Council of Guardians has frequently declared null

and void votes cast for some candidates. Finally the

overall

number of votes cast in elections is always massaged.

This is, after all, a way to claim greater legitimacy

among

the voting public for the entire system. This fraud, however,

always took place by common consent among the factions,

supposedly without damaging the electoral prospects of one or

other candidate.

What is totally unprecedented is what took place in June.

The world witnessed structural, nation-wide and highly organised

deception, led from the apex of the pyramid of power in favour

of one candidate that took not just the world, but a large

section of the ruling elite of Iran by surprise. The shape

and scope of this scheme was such that it would not be an

exaggeration to state that Ahmadinejad, a commander in the

Revolutionary Guards Corps, took over the presidential palace

through a blood-less coup or as revolutionary guard commander

Zolqadr said afterwards "in a complex way ... and

[through] multi-layered planning" [5].

These elections were also held at a time of unprecedented

developments in the region. As far as the Middle East is

concerned, Iran is in a very strong position, mainly thanks

to the military interventions of its long term "foes",

the United States and Britain. To the East, the Taliban regime

(with whom it nearly went to war in the late 1990s) is defeated,

and many of Iran's allies are back in power as regional

warlords, such as the governor of Herat province in western

Afghanistan under the pro-Iran warlord Haji Ismail Khan.

However Iran's main international success has been

achieved in Iraq. Without firing a single shot, they have

seen not only the removal of Saddam's secular Ba'thist

regime -- a neighbour they hated more than Israel and

the US -- but the coming to power of their protégés,

the Shi'a parties and militias of "Islamic Daawa" (the

Iraqi occupation Prime Minister's party) and other

major parties in the Shiite United Iraqi Alliance such as

the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI),

sharing power with the Kurdish PUK and KDP. All are organisations

well known for getting military, financial and political

support from Iran since the 1980s. This, together with

chaos created by military occupation in Iraq is part of the reason

why the Islamic regime in Iran felt confident enough to

take

unprecedented risks in these elections.

As a result of this

election, for the first time in the life of the Islamic Republic,

virtually every organ and institution

of power, electable or otherwise, has been handed over to

the complete control of the conservatives. It would appear

on the surface that political power is now homogeneous and

concentrated at the apex of the regime, in the hands of its

Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. However, there

is evidence that the coup d'état that was carried

out behind the curtains of elections was not just directed

against reformists, or the leading candidate Hashemi Rafsanjani,

but against the majority of the existing groupings in the

ruling oligarchy [6].

There is no doubt that, Ahmadinejad and his supporters

belong to the conservative wing of the ruling bloc. However,

among the various conservative circles, Ahmadinejad, in

particular belongs to groups that have been named radical new-conservatives.

He was one of the founders of the groups called Alliance

of Builders of Islamic Iran (Abadgaran) and Devotees (Isargaran).

Over the last few years, encouraged and supported by

the Supreme Leader, these groups have been taking root,

predominantly

in the security-police and military organs. They espouse

populist-Islamist and value-based slogans that distinguishes

them from the other conservatives. It is also clear that

in the pre-election bargaining of the various ultra-conservative

factions, Ahmadinejad was not acceptable to all and the

conservatives

went into the elections with four candidates.

As a result of the June election for the first time in

a quarter of a century a military man, rather than a mullah,

takes over as head of the executive. This almost completes

the trend of military-security control of the main organs

of state, which began at the end of the Iran-Iraq War,

and gained momentum over the past 8 years. This trend began in

the municipal council elections when the abadgaran took

control of many towns and cities two years ago and was consolidated

when they went on to control the Majles (parliament). The

point cannot be overemphasised that this is an entirely

new

and qualitative change, one that could have a decisive

influence on the relation between barracks and mosque in a theocracy.

The open interference by the supreme leadership apparatus

[Khameneis entourage] in the "elections",

the key role of the military and para-military apparatus

in shaping and organising the vote, and ultimately the coming

to power of the populist new-conservatives was an act which

was contrary to the norms in the present political culture.

Not surprisingly it gave rise to an unprecedented wave of

protest from among the ruling elites.

Such behaviour can

undoubtedly upset the line-ups within the regime and place

the leadership apparatus, and specifically further isolate

Ali Khamenei. It can weaken his position among the

clerical oligarchy, which for nearly three decades has

held real power in its hands. It is not beyond the bounds of imagination

that the Assembly of Experts [7], despite being controlled

by conservatives, will question his suitability to continue

as leader.

Rafsanjani's recent proposal to replace

the Supreme Leader (Khamenei) with a Council of Leadership

could well be taken up seriously with the support of

other influential clerics. So, why take such a risk? How can

one

explain this political purge that took place under the

guise of elections? What are its possible consequences?

Why the coup?

The 9th presidential election was a stage where the crisis

engulfing the regime and the solutions that could harness

these crises were simultaneously played out in the shape

of an aggressive struggle for power. It took place at a time

when the existence of the regime was seriously threatened

from three directions: At home the regime is fast approaching

a crisis of control, increasingly isolated and assaulted

by a general wave of disaffection and protest. Meanwhile

the regional and global noose is tightening in pursuit of

Bush's project of "regime change". Finally

within the regime the factional splits and quarrels have

made it impossible for the ruling elites to take decisive

decisions and act in a united way.

These crises, of course, have structural causes [8] wedded

in the contradictory nature of power in the Islamic Republic.

They were born with the regime, and have steadily worsened

over the last two decades, in particular after the adoption

of neo-liberal policies and the application of the structural

adjustment programmes. They have been deepened, more recently

by Bush's post September 11 policies, to the extent

that today the regime finds itself faced with real dangers.

Over these years, and in response to the regimes crises,

the rulers gradually lined up, gelled into two different

politico-ideological camps. Self-styled "reformists" faced

conservatives. The former believe that without "reforms" the

system cannot survive, although they hold different views

as to what "reform" entails. Some limit it to policies

and ultimately the conduct of the state in relation to the

people, in particular in the social and political arena.

Others go as far as institutional reforms in the power-structure.

For instance they want a change in the constitution to increase

the relative power of elected organs in relation to those

that are appointed [9]. They also want to normalise and "reduce

tension" in foreign relations, and abide by international

norms. This, they believe will guarantee the survival of

the system and hence their hold on power.

During 1999-2001 the "reformists" attracted the

support of a large section of the population and clocked

substantial victories in a chain of elections, occupying

almost every institution up for election. Yet at the very

moment of victory their dream turned to nightmare.

It became

obvious to all but the most blind that this repressive

and reactionary regime is not only immutable, but the institutional

power structure is intertwined with the interests of the

ruling groups such as to make any reforms impossible. In

addition the appalling consequences of the economic policies

of the reformists on the daily life of the millions, had

not only created major disappointment, but made inevitable

the prospect of growing protests.

The international scene fared no better, and September

11 put an abrupt end to Iran's efforts to normalise

foreign relations. Khatami's "dialogue of civilisations" foundered

when Bush placed Iran among rogue states and officially declared

a policy of regime change. It then became obvious that, contrary

to the hopes raised by Khatami's inauguration 8 years

before, in a changing world political environment his discourse

and foreign policies cannot provide the regime with any protection

against outside threats.

The effect of these setbacks was,

on one hand, to weaken the position of the reformist faction

within the overall ruling structures, subjecting them to

greater pressure from the conservatives. And, on the other

hand, destroyed the internal cohesion of the various groupings

that made up the "reformist" alliance. The result

was repeated schisms and splits.

The conservative bloc has

a different strategy to deal with the burgeoning crises:

Concentrate power more and more

at the top and use naked repression and terror through the

military and police apparatus. All the cliques within this

bloc oppose any change in the institutional structure of

power, especially if that means reducing the authority of

the leadership apparatus [10], which to them assures the "Islamic" foundation

of the entire system. They are convinced that any flexibility

in "principles and values" will lead to oblivion,

and should be ruthlessly resisted.

Indeed conservatives aim to simplify

the muddled and contradictory aspects of the regime by

doing away with the semi-elected republic in favour of a self-appointed

caliphate, with a highly centralised structure [11]. Conservatives

also viewed any openness in the political atmosphere or

the

formation of any form of independent social or political

associations as a dangerous threat to their total control

of society. Faced with the erosion of politically mobilised

social support for the Islamic Republic, they turned to

hired military and mercenary forces as their sole instrument of

control.

On the international level the conservatives prefer to

play the card of Islamic movements, terrorist activities

and politico-religious conflicts. They also try to open

up whatever breathing space they can by manoeuvring in the gaps

and on the competing interests among great powers, in particular

looking towards China, Russia and Japan. To achieve this

their main weapon is commercial and economic concessions.

Notwithstanding such policies, however, they have not flinched

from making behind the scene deals and concessions, if

it

served to consolidate their power, nor to use the nuclear

weapons card.

The conservative bloc, particularly since

the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, had occupied all the key positions

of

power. These included all the organs that came under the

command of the Supreme Leader -- the armed forces, the

police intelligence apparatus and the judiciary. Moreover

control over the Council of Guardians, by drawing red lines

that cannot be crossed, permits control over every branch

of state, including the state bureaucracy and the executive.

Yet

the despotic and intensely reactionary nature of the various

cliques within the ultra-conservative bloc severely

limits their ability to deal with the emerging crises.

Indeed within a few years after the revolution of 1979 they themselves

became the main cause of political and social crises, pushing

the latter to bursting point. This may be a reason why

throughout

its entire life this bloc could never extend its support

base beyond the military and quasi-military networks and

the people under the direct umbrella of the charities run

by them.

Their track record in dealing with the crisis

of legitimacy and the ever-escalating isolation of the regime

has been dismal. This can be seen in the proportion of

votes for their candidates -- never exceeding 25% of the votes

cast. They only became electable when the rest had boycotted

elections [12]. This fact was one reason why, at least

for the last 10 years, they were content to tolerate the rival

bloc's control over the executive machinery and the

legislative Majles, while keeping a tight grip on the

protective shield of the security forces.

With the failure of the reformists to keep their support

base, their inability to act as a safety valve for the

entire regime, the failure of their foreign policy to provide to

provide a partial shield against US threats, the conservatives

faced a new quandary and starkly precarious conditions

[13].

They had only two choices: compromise and abandon the ruling

political system in a step by step posses of isolation,

or face a deadly confrontation and put up with the consequences.

Faced with this Hobson's choice the conservatives split

into various factions: The Alliance of Builders of Islamic

Iran (abadgaran), Principled Reformist (usul-garane eslah

talab) etc.

These new groupings, which could be called Islamist new-conservatives,

carved their place in the political spectrum of the country

by being critical of and rejecting all other factions:

the reformists (supporters of Mohammad Khatami), pragmatists

(supporters of Rafsanjani) [14] and traditional conservatives.

In their view all three, had failed in practice, and indeed

exacerbated the crisis such that the very existence of

the regime was threatened. For the new-conservatives, recourse

to an immediate, bold and radical solution seemed unavoidable.

And this is what they did -- a slow consolidation of

power followed by a silent coup.

Over the last few years the new-conservatives had managed

to quietly infiltrate many organs, outwitting their rivals

to end up controlling many town councils, the Majles and

now the presidency.

New-conservative policies

The new-conservative groups, emerging predominantly from

within the armed forces and working under the umbrella of

the leadership apparatus, aim for a new equilibrium. This

is an equilibrium that will reduce the internal and external

crises and ensure the survival of the system.

The aim is

to create a powerful, centralised, principled state, cleansed

of corruption, one that can count on renewed support from

the lower sections of society, the military and semi-military

forces, armed with nuclear weapons, all funded by petro-dollars.

With these tools they believe they can confront both internal

and external challenges without resorting to any structural

changes, while maintaining the ideological-authoritarian

nature of the regime.

The difference between the new-conservatives and the more

traditional conservatives lies in:

First, prioritising destitute

masses to win back their support for the regime.

Second,

on their definition of the state. Theirs will be an interventionist

state, a state that will control all the main lifelines of

the country, quite unlike the "privatised" variety

of the traditional conservatives.

Third, on focusing their

slogans and discourse on social justice and the welfare

of poor rather than on Islamic values and the question of haq

va baatel [right and wrong in religious matters]. This

grouping, however, is still in the process of development, and

their

exact policies are somewhat ill defined, indeed in the

making. The broad outlines can, however, be deduced from statements

and utterances of its spokespersons. There are two central

solutions.

a. To centralise power at the apex and embark on a political,

organisational and financial purge of the executive body

of the state. What they hope to do is to harness internal

tensions and to block any effort by opponents to use internal

splits to further their aims. These are reflected in such

slogans as the fight against bureaucratic corruption, the

state aristocracy, and the rentiers.

b. The attempt to form a new political movement in order

to rekindle the social base of the regime, in particular

among the urban and rural poor -- something that had

gradually eroded over the last 15 years. In fact they are

trying to ride the popular discontent of the victims of the

economic policies of the regime. Here they hope to cultivate

the right material to help them rebuild the crumbling fortifications

of the regime.

Moreover, they might well be in need of cannon

fodder were the conflict with the US and Israel to escalate.

The role of such slogans as social justice, the fight against

inequality, the anti-poverty drive, the "taking the

oil money back to the people's table", the solution

to the housing problem, employment and marriage of youth

and such like is precisely to serve this purpose.

Some supporters

of Ahmadinejad have referred to this as the "third revolution" one

that instead of clergy or students has its leadership in

the military [15]. This

revolution is being born in the barracks rather than mosque

or university. Others see this is a rebirth of the idealism

of the early revolutionary years and a re-emergence of Islamic

populism [16].

It was along such a trajectory that the unannounced alliance

between a number of new-conservative groupings under the

leadership of Khameneis circle were able to lead the

recent elections, through a carefully planned and executed

plan with "headlights off" until the eve of the

second ballot, to go on and occupy the last bastion of the

reformists and pragmatists [17]. The ground is now ploughed

for the absolute rule of the velayate faqih -- something

the late Ayatollah Khomeini had called for but failed to

implement successfully - foiled by the deep contradiction

of his regime [18].

Does this scheme rest on real capabilities, real ground

and real potentialities? If successful can it save the

regime from the quagmire it is sinking in? Or is this just a moribund

attempt with no other outcome but further weakening of

the

regime, its greater isolation and a speeding up of its

implosion and collapse?

Can the new-cons do the impossible?

To answer these questions we will consider the real conditions,

potentials and limitations faced by the Islamic Republic

today. However it is important to first clarify a few issues:

1. The crisis of the Islamic Republic has structural roots.

They are above all the expression of the incompatibility

of a religio-ideological ultra-reactionary regime with its

material surroundings and historic setting. It is no surprise

that the Islamic government has been in continuous crisis

since birth, repeatedly surfacing under various guises and

at numerous levels. The constant need for political and structural

changes has been an inevitable necessity.

At best these efforts,

which surfaced as political U-turns, have merely shifted

the epi-centres of such crises from one area to another --

avoiding an explosion without removing the underlying causes.

Every time the question was the same: What are the regime's

capacities, where are the U-turns heading and what would

be the passing effects of any change in policy?

For the mullahs

ruling Iran, such crises were the norm. We have therefore

witnessed a move from "principles" to "expediency",

from elitism to populism, from decentralisation to the reverse

and back again -- always in search of stability! [19].

2. In the current domestic and international conditions

the Islamic Republic cannot find a solution to survive without

totally negating its very existence. The stark choice it

faces is either to submit totally to colonial conditions

(either keeping the religious appearance or under a secular

mask) as have some its neighbours, and to dissolve in Bush's

plan for a "larger Middle East", or surrender to

a progressive participatory and radical democracy.

Despite

all the outcries and widespread claims to the contrary,

there is no third road. No matter how daring the manoeuvres, or

how unexpected the changes and shifts in power and policies,

this regime will face a fresh deadlock sooner rather than

later making its collapse inevitable.

3. The Islamic Republic

has come out of the latest election weaker than ever, and

will embark on yet another political

U-turn, creating an even greater level of instability. There

are two main reasons for this. Firstly in order to make to

entice the population to participate in the electoral process,

it has had to retreat from what was always considered its

fundamental principles and values. The rulers were forced

to recognise, and even consider some of the political, economic

and cultural demands of the people. We saw them apologising

for the dismal record of the last 3 decades. Even more astonishing

was how all candidates avoided issues relating to "Islam" and "revolution" and

directly or indirectly criticise the authoritarian and oppressive

nature of their own regime [20].

Moreover, in this election, candidates on both sides of

the political spectrum encouraged negative voting. People

were asked to vote to reject, rather than to support a

particular candidate or slogan. Reformists and pragmatists encouraged

people to vote against reaction, despotism and to guard

against

the danger of fascism (meaning Ahmadinejad). Conservatives

asked people to vote against corruption, inequality, poverty,

and the plunder of public resources (meaning Rafsanjani)

[21].

Yet despite all the departures

and all the tricks, and in spite of the usual threats of dire consequences

of voting

abstention, official sources admit that only 28 of the

48 million eligible were dragged to the polling booths (this

figure includes the rigged votes). In circumstances where

most of the opposition, the ones who call for an overthrow

of the Islamic regime, had asked for a boycott, the absence

of 40% of the voters, rather than a sign of disbelief or

indifference, is a clear and unambiguous sign of widespread

opposition to the very existence of the system [22]. Yet despite all the departures

and all the tricks, and in spite of the usual threats of dire consequences

of voting

abstention, official sources admit that only 28 of the

48 million eligible were dragged to the polling booths (this

figure includes the rigged votes). In circumstances where

most of the opposition, the ones who call for an overthrow

of the Islamic regime, had asked for a boycott, the absence

of 40% of the voters, rather than a sign of disbelief or

indifference, is a clear and unambiguous sign of widespread

opposition to the very existence of the system [22].

4. In its quest for political homogeneity and unanimity

in power, the regime was forced to jettison the ruling

alliance that had lasted nearly three decades, an alliance that

helped

the system maintain stability. Now, for the first time

in its entire existence, the Islamic Republic has to be answerable

to its various challenges, both domestic and external,

without

the help of reformists and pragmatists in key positions.

At a time when it has little room to manoeuvre, the regime

has lost one of the main weapons it has used successfully

on so many occasions to sow indecision among its domestic

and foreign opponents [23]. From now on it has to face

its crises head on, and in doing so to rely on its last resource,

the military barracks, to keep its balance.

The country is increasingly in military hands. Significantly,

on the road to creating a military state, the special position

and stature occupied by the clergy has been uniquely questioned.

For the first time in 25 years a non-cleric is president

-- and a military man to boot. The logic for the central

role of

velayate faqih - the embodiment of the monopoly of rule

by the clergy -- and the very basis of Khomeini's

vision of Islamic government -- has been abandoned.

5. Moreover, by choosing Mahmood Ahmadinejad, an extremist

counter-intelligence officer in the Revolutionary Guards,

with a history of involvement in terrorism and murder [24],

to head the executive, foreign relations, even attendance

at international gatherings will become more problematic

than ever before. In particular with the nuclear weapons

issue the US and Israel are in a better position to incite

international public opinion against the Islamic Republic.

Now, any judge or attorney anywhere can try their hand

at prosecuting the second person in the Iranian government.

Not yet ready to fall?

Is the regime, then, ready to fall? Notwithstanding the

fact that the Islamic Republic has come out of this election

weaker and more fragile than before, one cannot necessarily

conclude that it is on the threshold of immediate implosion

and collapse. It is likely to continue its existence for

some time yet. The future of the regime rests on a number

of factors and the way they interact. Some of these factors

may allow the regime a breathing space while others will

do the opposite:

Will Iran's rulers be able to implement a series

of rapid new-conservative reforms to rekindle the support

of a significant section of the destitute masses [25]? Can

an anti-popular, utterly reactionary, despotic and authoritarian

regime, which was once able to use support from the "dishinherited" to

maintain power do so again? Can a regime, which in pursuit

of exporting its revolution, sent these supporters to clear

minefields for eight years, dangling a plastic "key

to heaven" round their neck, be capable of regaining

their trust? Will the people who had been betrayed once consent

to being betrayed again [26]?

There are two possible answers to these questions:

Affirmative: If it makes good use of the opportunities

offered, especially those resulting form the US occupation

of Iraq and Afghanistan , the Islamic regime can mobilise

some of the poorest in its support and survive the current

crisis. These opportunities include the quagmire of Iraq

(which could help the Islamic Republic play its Shi'te

card), the current buoyant oil market and the way any new

crisis in the Middle East might influence oil prices, the

significant foreign exchange reserves they have accumulated

and the surplus earnings due to the current high oil prices.

These could be channelled into immediate improvement in

the living conditions for targeted sections of the population

and reduce discontent among them.

Then there is the deep crisis among

the ranks of the opposition forces whose potential to fill

the current political vacuum

has shrunk. There is also the weakness and disunity among

radical and progressive forces that could have helped activate

the existing class divisions and use it to organise and mobilise

the independent organisations of workers and toilers. And

finally if they successfully use the basij -- a nationwide

political-military organisation [27] that it controls, and

the wide network of mosques and associated charities, as

powerful means of communication between the state and the

deprived and marginalised masses. Then there is the deep crisis among

the ranks of the opposition forces whose potential to fill

the current political vacuum

has shrunk. There is also the weakness and disunity among

radical and progressive forces that could have helped activate

the existing class divisions and use it to organise and mobilise

the independent organisations of workers and toilers. And

finally if they successfully use the basij -- a nationwide

political-military organisation [27] that it controls, and

the wide network of mosques and associated charities, as

powerful means of communication between the state and the

deprived and marginalised masses.

Negative: If the new political cliques in power cannot

overcome some of their contradictions the obstacles they

face both within and outside the ruling apparatus. These

obstacles are:

Creating a new balance between the economic interests of

the mafia-like rentiers at the top and the demands of the

dispossessed masses [i.e., the core element of the new-conservative's

strategy]: Being able to redistribute public resources (especially

oil income) to reduce the burdens of life. This will require

cutting all or at least some of the tentacles of an insatiable

monster. An octopus with one end in the inner circles around

Khamenei and the numerous institutions under its tutelage,

and tentacles in the Revolutionary Guards, the security apparatus,

the newly built palaces of the top families, and the offices

of their offspring (popularly known as the aghazadeha = sons

of clerics). In other word, being able to keep the promise

to have the "oil money on the table of the poor" and

to create hope.

Neutralising the immediate and savage resistance of capital -- both

domestic and foreign - which will view the slightest deviation

from its model of neo-liberal economy and austerity as anathema:

Being able to gain its confidence and to sell them an economic

policy full of contradictories and ambiguities. And to prevent

domestic and foreign capitalists using their most effective

weapon, flight to other places, thereby squeezing the economy

and increasing unemployment [28].

Repressing or overcoming the demands of working people,

key agents of socio-political change. Given the radicalisation

of such demands by the masses, the regime will need to block

efforts to organise at various levels; to entice working

people to blindly follow yet another "saviour",

it will have to split the ranks of the labour force, and

to isolate the more radical sections of the labour movement

[29].

Controlling the political context within which the regime

operates: That is to say, first of all, to crush the popular

movements for social equality, cultural and political freedom,

and self-governing. Being able to create an environment

of fear such that anti-despotic movements, and in particular

women, youth, intelligentsia, and non-Fars nations and

ethnic groups are controlled. Being capable of suppressing the

rising

waves of cultural and civil disobedience and political

protest. In short, producing a schism between the demand for bread

and that for freedom.

Stabilising the regime's relationship with the world

most powerful states: In particular, preventing the nuclear

weapons issue from becoming explosive, and hence being

able to divert petro-dollars as before to the state coffers.

And finally, preventing the crises

outside from infecting the corridors of power and fracturing

the political and factional

homogeneity achieved by the present coup: That is to say,

preventing the singularity of decision-making being destroyed,

giving way once again to factional squabbles, obstructions

and such like, this time between the existing military-economic

mafias in the conservative faction. And finally, preventing the crises

outside from infecting the corridors of power and fracturing

the political and factional

homogeneity achieved by the present coup: That is to say,

preventing the singularity of decision-making being destroyed,

giving way once again to factional squabbles, obstructions

and such like, this time between the existing military-economic

mafias in the conservative faction.

There is little evidence that new-conservatives in Iran

will raise once more the flag of social justice in a "third

revolution". If the "first revolution" was

a real tragedy, the "third revolution" will probably

be nothing more than a nauseating comedy.

Yet the key to the puzzle of Ahmadinejad is in the hands

of the working class. Emergence of a progressive, radical

and mass working class movement is the only development

that could fill the current ideological and political vacuum

within

which reactionary populism of Ahmadinejad is trying to

act. A class that is the only social force capable of preventing

demagogic populism [30].

The crucial issue facing Iran, however, is not the fate

of Ahmadinejad. It is the fate of the country. It does

not require much imagination to understand that the Islamic

Republic

has a mortal disease. Ahmadinejad's remedy is only

temporary. Inevitable death awaits this regime, so out

of keeping with its era. What Ahmadinejad and the regime

are

vainly trying to save is already doomed.

But the fate of the country is not inevitable. In the manifold

crises facing Iran, will the country face collapse and

break-up, invasion or a real liberating future? That choice, and

that

future, is being made today. And the answer is clearly

not preordained nor totally dependent on how, or at the hands

of whom, the Islamic regime falls.

This future is once again in the hands of the organised

working class of Iran. Will the working class be able to

tie its strategic potential to the energy and creativity

of the social movements? Would it be capable of giving birth

to a real agent for social change through combining organisation

and organisational ability? If the answers to these questions

are positive, then not only the swamp the Ahmadinejads of

Iran want to use to create another ultra-conservative and

reactionary movement will dry up, but the country will avoid

the threat of collapse, break-up or invasion. "Otherwise

there will be silence, and silence is our sin!" [31]

The experience of the last eight years has proved that

a heavy penalty awaits those that are unable to use the

opportunities facing them to create something new and surrender

to the

idea of reconciliation with reality. With the advent of

the ultra-reactionary new-conservatism, those movements who

fail

to take up the occasion provided today to move to a better

life, and to a different world, are without doubt going

to face a more savage penalty. The experience of the last eight years has proved that

a heavy penalty awaits those that are unable to use the

opportunities facing them to create something new and surrender

to the

idea of reconciliation with reality. With the advent of

the ultra-reactionary new-conservatism, those movements who

fail

to take up the occasion provided today to move to a better

life, and to a different world, are without doubt going

to face a more savage penalty.

This article was first published in Iran-Bulletin,

Political quarterly in defence of democracy and socialism

Notes

1. An all-powerful 12-man committee appointed by the Supreme

Leader and given veto rights on elections and laws that in

their view are incompatible with "Islam". In the

latest election only 8 of over 2000 candidates passed its

veto and were allowed to go on the ballot paper -- and

even here the two reformist candidates, Mostafa Moin (Minister

of Higher Education in the outgoing government) and Mehralizadeh

were only reinstated after serious protest.

2. See "Iran: Majles election boycott. What next?" Iran

Bulletin - Middle East Forum series II no 1 p 2

3. This is a fundamental difference between elections in

the Islamic Republic and normal parliamentary democracies.

The Iranian electors are highly politicised and have shown

their ability to use the ballot box very adroitly to play

the political field in highly undemocratic conditions pertaining

to the country. See for example Presidential elections: What

if the magic fails. iran bulletin 1993 no 2 p6; Majles elections

iran-bulletin nos 25-26; "Iran: Majles election boycott.

What next?" Iran Bulletin - Middle East Forum

series II no 1 p 2

4. What some western analysts have called "democracy

Iranian-Islamic style"

5. There is evidence that a coup-like plan, kept carefully "blacked-out" until

24 hours before the second round of elections, was put into

motion. Ahmadinejad , who had been trailing in the first

round of elections until counting was well underway suddenly

emerges as the challenger to Hashemi Rafsanjani to the open

protest of the other runner up, former Speaker of Majles,

Mehdi Karrubi. Ahmadinejad 's campaign distributed

5 million copies of a CD, almost exclusively in the poorer

districts of the country, which showed Rafsanjani and his

family living in luxury while Ahmadinejad was portrayed living

a simple life and giving away most of his salary to the poor.

Then in the second round the Basij (militia) troops put into

effect a "headlights off" plan in which each of

the 1.5 million strong Basij had to bring 10 persons to vote.

See Shargh news paper (Farsi) 14 July 2005. Chief of Revolutionary

Guards Corps, Zolqadr addressing in a large meeting of the

Basij: "in the complex political situation when foreign

powers and extremist currents inside have for some time been

determined, and planned, to change the result of the elections

in their favour and to prevent the emergence of an efficient

and principled government, we had to act in a complex way

and the principled forces, thanks be to Allah, through correct

and multi-layered planning, were able to get the support

of the majority of the people in a tight and real competition ... " Sharq,

Teheran July 2005 (in Farsi).

6. There were eight candidates. Moin and to a lesser extent

Mehralizadeh represented the reformists. The pragmatist Rafsanjani

was very much a compromise candidate who came in at the last

minute and was expected by all commentators to win. Others

were Karrubi who represented the Society of Militant Clergy -- with

some links to the reformists. The rest belonged to various

conservative factions. These were former police chief Gjalibaf,

Ali Larijani the Supreme Leader's representative on

the National Security Council and of course Ahmadinejad .

7. The Assembly of Experts is elected by the voters every

8 years from among senior clergy (defined as those with "knowledge

and wisdom"). Among their role is to elect the velayate

faqih -- the supreme leader to the Islamic Republic who

in turn has absolute power over the entire civil and political

society.

8. See Ardeshir Mehrdad. "The road to a terminal decline:

alternatives split society at one end even as it is united

in another" Iran Bulletin 1995, nos11-12 p6

9. The velayate faqih appoints most influential posts.

In additional to the Council of Guardians, he appoints the

heads of the arm forces, the judiciary, and has "representatives

of the velayate faqih" in virtually every organ.

10. The present vali faqih: Seyyed Ali Khamenei.

11. The dual structure of the Islamic Republic rests of

two pyramids. One the religious-political pyramid at the

apex of which sits the Supreme Leader -- Ali Khamenei.

The other the executive presidency based on a parliament

and presidency elected through tightly regulated and controlled

electoral procedures. See Ardeshir Mehrdad. Will Iran' political

system absorb civil society or be overcome by it. iran bulletin

1998 no 19-20 p10

12. As happened in the last elections to the Majles and

the municipal councils. See Iran Bulletin - Middle

East Forum Series II no 2 p

13. Key elements in this quandary were the failure of the

project to "reform civil society" and the increasing

poverty and failure of the economic privation programme.

14. Known in Iran as Kargozaran Sazandegi = agents of construction

15. Khomeini called the occupation of the US embassy in

1981 the "second revolution".

16. Kaveh Afrasiabi. The Ayatollah's Reign, June28,

2005, Asia Times.

17. See ibid footnote 5.

18. See Ardeshir Mehrdad. "Velayate Faqih -- a system

on its deathbed" Iran Bulletin 1998 nos 17

p6

19. For example when the clashes became paralysing Khomeini

created a new organ to stand above all other organs: the

Assembly for Expediency. See "Where does the Assembly for

Expediency fit" Iran Bulletin 1998 nos 17

p9

20. Unlike previous occasions there was little effort to

use religious orthodoxy as a powerful weapon to get voters

into the booths. Instead each candidate tried to distance

themselves as much as possible from the past and to absolve

themselves from any responsibility towards it. This was most

obvious with Ahmadinejad who, as a relatively unknown figure,

made greater use of this ruse with benefit. Moreover such

influential bodies as the Society of Teachers at the Qom

Seminary, the Teheran Society of Militant Clergy, the Assembly

of Militant Clergy, the Islamic Coalition Party (Hey'at-haa-ye

Mo'talefe), who had played such crucial roles in previous

elections, their support being critical for getting the vote,

were sidelined and few candidates were happy to be officially

linked with any of them.

21. A negative vote is not always a protest vote, or even

a boycott. It can also be a vote to prevent things worsening:

a choice between bad and worse.

22. This is exactly the opposite to what Ali Khamenei tried

to imply, and some opposition forces echoed. Presence in

voting booths cannot be automatically put to the account

of the legitimacy of the regime. A negative vote to the record

of the regime is not necessarily a positive vote for its

existence.

23. Right up to the recent election many opposition forces

had used the presence of the reformists within the regime

as a chance for a peaceful transition to a post-Islamic Republic

era. The same hopes had been used by, among others, the EU.

24: See for example Enghelabe Islami for details of Ahmadinejad

's involvement in the murder of Kurdistan Democratic Party

leaders

in Vienna (in Farsi). See also for other references.

25. The experience of the Iran-Iraq war is useful here.

Then it used this weapon to break the siege of domestic opponents,

while putting up an effective resistance to foreign invasion.

It now hopes to use the same weapon to reduce the capacity

of domestic opponents to manoeuvre and to prevent foreign

powers, and specifically the USA, to try a direct overthrow -- whether

by a velvet revolution, or a limited or unlimited invasion.

26. Can political Islam, as a mass-populist movement, reconstruct

itself in Iran after suffering a serious defeat, especially

in the framework of a system that is the institutionalised

expression of this defeat? It might be better to answer this

question in a separate article.

27. A "barrack-based party", as Mohammad-Reza

Khatami put it in an interview with HOMA TV, a satellite

channel.

28. A day after the election of Ahmadinejad the Teheran

Bourse lost 5% of its share value. The decline has continued

since and has not been reversed by the end of July. Iranian

State TV, Jaam-e jam, interview with head of the Iranian

Bourse. July 28, 2005.

29. There is no doubt that the populist slogans of Ahmadinejad

have found an echo in some of the poorest sections of society.

This has been pointed out by the international media, and

corroborated by independent sources. What is forgotten, however,

is that while most of the middle layers turned out to vote

for Rafsanjani, the majority of the 20 million who did not

vote belonged to these destitute strata. This signifies that

Ahmadinejad 's influence among the layers he has specifically

targeted remains weak. This does not bode well for the central

strategy of the new-conservatives.

30. In 2000 at least, 20-23% of the urban and rural households

lived under the absolute poverty line. See Nili et al, "Barrasi-e

tahavolaat-e faghr, tozi'e daramad, va refaah-e ejtemaa'ei;

Sazeman-e modiriyat va barnaameh-rizi-e keshvar; 1379 (Teheran,

in Farsi). The official rate of unemployment in Iran is 16

percent (Central Bank) and unofficial estimates are about

30%.

31. Poem by Siavash Kasrai'

|