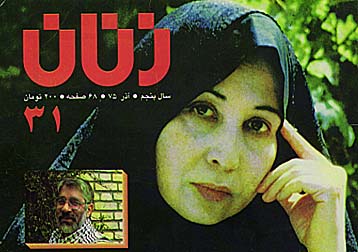

The December 1996 cover of Zanan

Agents of change

September 1997

The Iranian

From "God has ninety-nine names" by Judith Miller (1996, Simon & Schuster, New York) . Pages 454-456. Miller has been a correspondent for The New York Times since 1977. She was the paper's Cairo Bureau Chief from 1983 to 1986 and special correspondent during the Persian Gulf War.

The [reform] movement popularized its ideas through some twenty newspapers and magazines. While there are no truly independent newspapers and journals in Iran and though censorship remained pervasive and arbitrary, these independent-minded journals and newspapers, which appeared with official authorization, raised daring questions about Islamic government and promoted what they called a "reformist Islam," which strongly resembled what Western intellectuals call "secularism."

Among them Zanan (Women), whose feminist editor, Shahla Sherkat, feared that each issue might be her last. The government did not give free paper to Zanan as it did to other magazines, she complained, which made publication not only risky but expensive. Yet she and a tiny staff tackled issues at the heart of the Islamic Republic's discrimination against women, which she called "un-Islamic." Women's interest in their rights, if not rights themselves, had increased as a result of the revolution, she told me. Like so many critics, Sherkat had obviously learned how to articulate her antirevolutionary ideas in politically acceptable formulations. Perhaps she still believed in the Islamic revolution; perhaps she no longer did. I would never know.

But her criticism of the government's treatment of women was as scathing as that of any non-Muslim foreign critic. Her journal and another Farzaneh (The Clever Woman) [edited by Massoumeh Ebtekar, currently one of President Khatami's vice presidents], were among Iran's leading crusaders for women's rights, joining more than sixty non-governmental civic groups - some Islamic, some not - that shared the goal of the ending discrimination against women and government-sanctioned privileges for men.

Islam's hadith, the sayings of the Prophet, had been misinterpreted, she declared, pulling her chador more tightly around her chin; they were not consistent with real Islamic laws. Women in Iran were doctors, lawyers, engineers, newscasters, parliamentarians, scholars, businesswomen. Where does the Koran say that women cannot be judges, fighter pilots, or even leaders? Where does the Koran say that women must wear black? Colors are beautiful, and beauty is Islamic. Her issue on the topic of "color" sold well, she told me.

So did her issue on wife beating. Islam does not sanction a husband's physical abuse of his wife, she asserted. In a recent issue, Zanan argued that Iran's toleration of such abuses resulted from a mistranslation of the Koran's Arabic. Daraba , or beating, also meant "resting, avoiding, walking, preventing, staying home, changing, having sex with, and sharing a bed." Imam Ali, the article quoted Muhammad's cousin as stating, instructed a man first to "talk and preach to your wife." If she still refused to obey, he should refuse to sleep with her. If disobedience continued, he should "find a judge to settle the dispute between them." But "reactionary" elements in her country had ignored such counsel, sanctioning wife beating, a jahili, or pre-Islamic custom.

But beyond problems of mistranslation and misrepresentation, Sherkat added, treading now on dangerous ground, "what made sense in the seventh century may not make sense today." Muhammad was an enlightened man, she argued, a leader who valued women. Since Islam made sense for "all people in all countries in all times," the Prophet himself might not give today the orders he gave then. God's words had to be reinterpreted, updated so that they were applicable to modern life. Iran, for example, permitted citizens to marry at puberty, which it defined as nine for girls and fifteen for boys. "But people died younger in the seventh century. Today those designations are inappropriate."

Despite its circulation of less than ten thousand, Zanan was having an impact, Sherkat maintained. Women were being trained in Qum as mujtahids, interpreters of Islamic law. Eventually, they would help change the government's policies toward women. The Iranian Parliament, she noted, had recently enacted legislation giving women greater rights in divorce, although women still could not divorce their husbands. And the Judicial Council had recently ruled that women could be "consultants" in court cases - de facto judges. In several cases, their "advice" had been accepted.

A floor above Zanan is Kiyan (Essence), a quarterly magazine that has published Abdolkarim Soroush's lectures and essays. Mahmud Shams, Kiyan's dynamic editor, explained that the journal was founded in 1991 - without government-provided paper - to promote what he called "revisionist Islam," which endorses, among other "Islamic" civil rights, freedom of speech and of the press. "Since we are the children of this revolution, the militants view us as far more dangerous than secularists. For we fight them from an Islamic base."

Shams said that to become a modern nation, Iran must experience a "Reformation" as Christianity did in the West. But since Iran was deeply Islamic, the result would not be secularism, the topic of Kiyan's issue, which he defined as a "rupture between a society and its values." "Islamic revisionism" would provide greater freedom, tolerance and pluralism - "within an Islamic framework." This was Soroush's view as well, he said.

What enhanced Soroush's credibility was his impeccable Islamic credentials. As a former member of the government's senior Cultural Revolution Panel, Soroush had supervised university purges and book burnings in the early 1980s and defended the persecution of leftists. But just as [the late Ali] Shariati had argued for revolution to end social injustice through Islam, Soroush was now pressing for tolerance and political pluralism through Islam. No one could claim an exclusive right to interpret the Koran. There could be no "absolute truth" because understanding of Islam was relative. Implicitly, Soroush was arguing for the separation of church and state, though he had refused to confirm this when I had interviewed him. But Shams maintained that Soroush arguments implied that Islam could not, and should not, be transformed into an ideology. If Islam "ruled," it would be blamed for the failures of temporal rule. Islam had to remain above all that. For such ideas, Shams told me, many called Soroush "Islam's Martin Luther."

This "enlightened, rational" trend would inevitably win, Shams argued, because technology could not be stopped. Satellites, banned as a form of cultural invasion, were installed in every other home. Young Iranians traded jokes and information on the Internet, which the government had also tried and failed to shut down. Iranians would remain fascinated by the West and drawn to Western culture. The government had succeeded only in pushing all that it denounced as "un-Islamic" - promiscuity, alcohol, and satellites - off the streets and indoors. Iran had become not an "Islamic" country but a "twisted" land in which religion was now seen by a majority of younger Iranians not as a "choice" but as a set of onerous "do's and don'ts."

Ramin Jahanbegloo, who helped found Goft-o-gu (dialogue), a two-year-old reformist quarterly, argued that many young people were now "totally disillusioned" with religious values. The Islamic revolution had succeeded in producing among the young an areligious generation as well as a "James Dean Syndrome" - "rebels without a cause" - and a sharp generation gap between young Iran and the aging clerics who made the rules. Tehran's new cultural centers, which the mayor had expanded to attract teenagers, now featured computer and karate classes as well as jazz concerts featuring the music of John Coltrane and Dizzy Gillespe. The concerts were called "popular music of the blacks" to disguise their obviously American origin. Few were fooled, but even fewer knew how Iran could escape the Islamic trap of its own making.

Related links

* A

new generation? A paper by Prof. Afary

* Being

a woman in Iran. An interview with Prof. Nafici

* Kiyan

magazine online

* Abdolkarim

Soroush - News & views

* Seraj - The Soroush homepage

Web

Site Design by: Multimedia

Internet Services, Inc. Send your Comments to: jj@iranian.com.

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved.

May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

Web

Site Design by: Multimedia

Internet Services, Inc. Send your Comments to: jj@iranian.com.

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved.

May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.