From Shanghai to Kashgar From Shanghai to Kashgar

China is Seventy-Thirty

>>> Photo essay

Keyvan Tabari

January 24, 2006

iranian.com

abstract

When I was 24 and innocently presumptuous, I lectured about China in my classes on politics at Colby College. In 1962, the “East was Red” and Mao was its Sun God. My roommate then was the scion of a wealthy Shanghai family that fled from the Revolution to Brazil; he taught English literature at the College. Over the years, the conflicting sources of my knowledge about China grew ever more complex due to the surprising developments in that country. I also became wiser so as to acknowledge my inability to really comprehend “China”. The word now evoked a mostly visual response in me: I pictured the vast size of China on the map. It was in the hope of better managing the formidable concept of China that I decided to embark on a journey across its width, from the east seas to the western mountains. I sought a sense of the place. The sights of China beguiled me, and the variety of its people intrigued me. This report, however, is more about me, my experience in China.

keywords

Kashgar*Lanzhou*Dunhaung* Turpan * Urumqi* Xian* Shanghai* Beijing* Labrang* Silk Road*

***

Many a Miles to Go

It was five minutes to nine in the morning. The guard at the Chinese consulate in San Francisco, a young Russian émigré, was looking covetously at the shiny convertible Lexus which was parked at the curb. When he turned his face to me, the guard blushed, mildly embarrassed. I was thinking of how tempting it was to pontificate on the significance of this symbolic convergence of the trajectories of the world’s three greatest Powers on the emblematic Japanese export. Presently, however, I had to answer a more specific question posed by the Chinese visa officer who was examining my application: “Where is Kashgar?” I had a long, learning trip ahead me, and Kashgar was only one of the several unfamiliar cities in China I would visit. My application for a visa also included Lanzhou, Dunhaung, Turpan and Urumqi, in addition to the “regulars,” Shanghai, Beijing and Xian. “Is Kashgar in Tibet?” the young uniformed woman wanted to know. I told her no, it was in Xinjiang, which is a region of China proper. The visa officer checked this fact with her colleagues and, assured, told me that my visa would be ready the next day.

This was my first trip to China, but my interest in that country had a long history. China made me a news junky before I was 10 years old. I remember following its civil war of the late 1940s in the daily newspapers. Its staggering dimensions left indelible marks on my mind. Armies with millions of soldiers were contesting thousands of miles of territory in an epic struggle. At stake was the future of a civilization with two millenniums of glorious past. These big numbers provoked intense curiosity, but they also induced a certain feeling of futility: how could one possibly comprehend China! Indeed, it seemed that the more I learned, the more elusive the whole concept of China became. In chasing it, I became especially enticed by China’s meaning for the country of my heritage, Persia. Evidence of the globalizing interchange of these two cultures in ancient times abounded in the string of Silk Road settlements from Beijing to China’s western borders. I wanted to get a feel for these places, just as I wanted at least a glance at the Beijing and Shanghai that had evolved into a post-Mao hybrid of Communism and capitalism. Limitations of language and training would, of course, inhibit me from reporting on China, but I was after something else: cumulative vignettes of my own experience in China.

First Transaction

Outrageous charges by rogue taxi drivers are a common nuisance at international airports. In Shanghai I deflected three such hustlers before agreeing to go with the fourth after he reduced his price for taking me to my hotel from 40 Yuan, first to 35 and then to 30 (about 4 dollars). I would try my negotiating mettle in this fabled land of entrepreneurs, I rationalized. In reality, I was too tired to look any longer for the conventional transport at the end of a ten hour flight.

The car was not at the curb, which surprised me; we had to go to the parking garage. There we met the real driver; the party to my contract proved to be a broker. He sat with us, however, and we drove until we came to a toll booth plaza. Now the car stopped and the broker got out, telling me that he needed to go to the bathroom. The driver spoke no English. Soon, he left the car too. I saw him go and stand behind the trunk. I came out and saw another cab being flagged by the broker. He talked to the new cabby and told me that the latter would take me to my hotel. I was pondering my choices as the first driver started to transfer my luggage to the trunk of the cab. He then swiped his hands together as a sign that he had retained nothing. The broker now asked me to pay him the fair. I said I would pay at the hotel. The broker got some money -his cut- from the cabby, which made the latter look disgruntled. As I sat in the cab, to deal with my mild concern, I took its tag number. We reached my hotel without further incident.

Scenes from a City

Garden Hotel was chic and comforting. Here, for the first time, I saw a “Washlet Toto” which is a combination of Bidet and Spray with warm water. This hotel also had a pedigree. Built as Cercle Sprotif Francais in the French Concession district, and in that era, it was liberated by the Chinese Communist into the People’s Cultural Palace. Chairman Mao stayed there when in Shanghai. The hotel displayed no picture of him.

Next day, however, I was watching Mao Zedong on the television screen of Bus No. 26 in an operetta. As a young woman sang a heroic aria, the background film depicted scenes of glory from the Communist years -marked in decades, 1949, 1959, 1969, up to 1999- dominated by period pictures of Mao, Deng, and Zamin. There was only one shot of Chou En-Lai, standing next to Mao at the 1949 proclamation of the Communist State in Tiananmen Square, although I was to hear often that he was the most beloved of the Red Chinese leaders.

This was a morning commute bus. I had taken it to see ordinary Shanghainese going to work. I was the only non-Chinese looking person on the bus. It was full and I had to stand up, holding on to the straps that advertised the logo of 7up and its Chinese character. When there was a pause in the sound track of the television, the noise of a radio, which was also on, could be heard. Underneath both there was incessant conversation, reduced to a steady hum.

This particular public vehicle had a “star” sign which meant that it was air-conditioned and hence it cost more. A digital thermometer showed that the temperature inside was 23 degrees centigrade, 10 lower than outside. The conductor was a woman who never smiled but was uniformed and neat in her make-up, with big half-moon arches as eyebrows. She wore white gloves. So did the many traffic officers I saw on the streets outside. There were at least five of them at select intersections: one in the middle and one at each of the four corners. While at first this seemed like overkill, I realized it was necessary when I saw the chaos at those intersections which, inexplicably, were not attended by any traffic officer. The famous plethora of bicycles had not been replaced by the increasingly excessive number of cars in Shanghai; it was merely absorbed in them. I saw no accident, no fight, no armed police, no overt sign of an authoritarian regime.

Not everyone was hurrying to work this morning. I spotted men in their underwear, sitting on stools at low small tables on the sidewalks, playing games. I got out of the bus and walked. When I stopped at a street corner to write down my observations, I became an observed object myself. Passerbys took time to look with curiosity. They allowed me to take their pictures, even if we could not communicate much. At the counter of a food shop I bought dim sum and by motions asked for a napkin. Misunderstood, I was first given chopsticks and then toothpicks. I picked up a peach from a vendor who sat squatting on the ground in the fashionable Huailai Street. He weighed the fruit in a ancient scale held by hand. A wedding-clothes store was the busiest shop on that block. I inquired about internet cafes from a groom to be, and was taken to a “computer house,” a big hall where many teenagers were playing video games and chain-smoking while a tape played a Chinese singer botching the line, “Son of a gun, down by the Bayou”.

Bund and its Apparitions

The landscaped promenade that is the Western embankment of Hunagpu River was a good platform to see the Bund and the apparitions of its past glory as the heart of the cosmopolitan Shanghai of pre World War II. I looked across at the bell, “Big Ching,” on top of the Customs Building, which had been removed during the Cultural Revolution but restored in 1986 for Queen Elizabeth’s visit. Then I entered the Peace Hotel.

I went to see the fabulous Art Deco in the corridor just off the main lobby. Sharing my visit was a couple that spoke Spanish. I marked them as Argentine, for the woman had that special exquisite scent of feudal wealth and the man was polished almost to effeminate perfection. A charming partners desk caught my attention. The sign on it said “Assistant Manager.” He was not there. I sat in the guest chair. A smiling middle-aged woman approached me, followed by a man with an air of self-importance. She told me that she was from Israel but now lived in England. I happened to mention that “Bund” was the Anglo-Indian pronunciation of the Persian word band, meaning embankment. “Isn’t it a shame what has happened in Iran,” she uttered gratuitously, “Look how much progress these people have made,” referring to the Chinese. Her husband had the accent of the more established Jews of England. I was framing him in an imaginary Pinter play when he complained about the decline of the Peace Hotel, “We had to change our room three times here, before we got a decent one.” In the 1930s the Peace Hotel was the castle from which Victor Sassoon, an émigré Jew from Iraq, ruled over the financial Shanghai, and facilitated the refuge of over 20,000 European Jews here.

My Guide Becomes My Charge

I must have looked lost in the maze of Shanghai’s old town. A Chinese man in his early forties asked me if he could help. We struck up a conversation. I welcomed this as an opportunity to learn about a Shanghai “man on the street”. He said his “English name” was Steve; his English was halting but adequate. He was an accountant for a school district about 80 miles away. Steve was born and raised in Shanghai and his grandmother still lived here. He would come to visit her whenever he had vacation time.

Steve explained that the reason he could not find the street I was looking for was because Shanghai was changing so much and so fast. He pointed to the new high rise apartment buildings, “They were not here a few years ago. And these other small shops will be gone the next time I visit Shanghai.” He led me to a big store so that he could ask for directions. When there, he talked to a clerk and told me that we needed to go upstairs to see the manager. I followed him. They were serving tea on the next floor. Steve asked if I wanted tea. We sampled some tea. I asked about his parents. They were professionals. The Red Guards had inflicted so much indignity on them that Steve was bitter toward Mao. “He was a bad man,” Steve said unqualifiedly. We did not get into details.

Steve took a container of tea from the salesclerk and handed it to me. The price was 12 dollars. I figured this was how one paid for the tea tasting. I paid for the container as it seemed Steve would not have the money. I gave it to him as a gift. He said no, “You take it.” I said I had a long way to go in my trip and did not want to carry the tea. No, Steve insisted, “Maybe we could have dinner later.” This seemed like a moment when I could cause him to “lose face,” a big issue in cultural exchange. I resigned myself to buying him dinner in addition to dealing with the unwanted tea jar.

It was still a few hours to dinner time and we were running out of interesting subjects to talk about. I said I would want to go the “Saga of Shanghai,” the show that the hotel concierge had told me was “typically Chinese”. That was how I ended up paying for Steve’s theater ticket. The show was mostly acrobatics. The price was steep, and that became the core of our conversation at dinner which followed. Steve told me that he was yearning to visit Beijing and the price of that theater ticket would be enough for a train ride to Beijing. I was now looking around at our restaurant.

It was divided into several private rooms. In each room there was a television screen and a video player. In the room next to us, there was a group of people. One young man had a microphone in his hand and sang. The others served as a chorus. This was my introduction to karaoke in China. Steve did not suggest that we sing. Instead, he was busy ordering food. In addition to crab and shrimp which I liked, the waiter brought some dish which consisted of dark brown meat with darker skin on ribs. I found it too chewy, with an unfamiliar taste. Steve told me its name in Chinese which I never quite learned; he did not know what it was called in English. Later I learned it was sea turtle. Steve would take my portion with him.

The haste with which Steve ate once again reminded me of the gap between his meager resources and what a foreign visitor could afford. It made me uneasy. This was one reason I declined Steve’s suggestion that we explore the nightlife of Shanghai. He sounded surprised, “Eat and sleep?” When I said goodbye to him, Steve asked for money “to take a taxi to my grandmother as it is too late for buses”. This was not quite like a guide asking payment for his services. It occurred to me that Steve was not alone in finding it easier to ask for “favors” instead. Shanghai had an unusual number of beggars at its tourist spots.

Amy’s Boyfriend

I did not think Shanghai would be for prudish visitors, but its offerings were more blatant than I had expected. My hotel was in a gated compound where the taxis stopped at the entrance inside. The one night that I walked through the gate, I found it attended not only by the hotel security guards but also by prostitutes and pimps, each respecting the other’s turf. A woman greeted me longingly, and a man hustled me. “No money, just look,” he pointed his fingers at his eyes. Then he said “Massage, 30 dollars.” At the hotel I noted signs advising that guests register their visitors. In its elegant lobby, a demur Chinese girl was playing classical music on a grand piano. I ordered a drink and sat not far from a man with a green jacket. We began a conversation. He was ahead of me by two drinks, and jovial. He told me that he was from Central America and on a business trip. We talked about Garcia Marquez and he told me about a new book by the famous author about a virgin prostitute. I told him about what I had just seen outside our hotel. He laughed and told me the following story which I will try to recall here faithfully:

“I was walking on Nanjing Lu earlier tonight, quite impressed by its lights. You know, it reminded me of Times Square, except bigger. These two young girls came up to me. One asked my name, and introduced herself as Amy. She said that she was a college student and wanted to practice her English. She asked me where I was going and I told her that I was looking for a restaurant to eat dinner. Now her friend, who had taken a few steps away, joined us. They said they had eaten but offered to show me a good restaurant. We went to a ‘Barbeque’ place. Amy was becoming increasingly friendly. She was calling me ‘my boyfriend,’ and holding my hand. She asked me ‘what is your job?’ I told her that I was a banker. She took out her little translation gadget and punched in ‘banker’ as I spelled it for her. Chinese characters came on the LCD and the gadget said ‘banker.’ She repeated ‘banker,’ as she looked at me admiringly. We were given a private room. There was a television screen and a karaoke video machine there. Amy’s friend turned them on and began to sing. They ordered food and drinks, at first only the few items I wanted, but then more. The friend now ordered Scotch. Amy was affectionate toward me, while the friend was telling me to drink her Scotch. ‘Let’s get crazy,’ she said. I was amused at first, but eventually I said ‘let’s not order any more.’

They brought the check. I looked at it and it was far beyond the amount I had feared. It was for $750. I refused to pay. A man with dyed blonde hair, a lilt in his voice, and dramatic motions appeared and demanded that I pay for what ‘your girl friends ordered’. I said his bill was outrageous and I only had 100 dollars on me. He said he would take a credit card. I said I did not have my credit card or debit card with me. When he acted agitated, I said we should call the police to settle this matter. ‘Why the police? The police is for criminals. Are you a criminal?’ he said. I did not yield. The fellow eventually offered a compromise: ‘I give you 20 percent discount.’ I did not accept. Now an older Chinese man came to us. He seemed to be the owner and more pragmatic. He did not speak English, but obviously had a moderating influence on the other fellow. He now asked the girls how much money they had. Amy said she had nothing, but her friend had the equivalent of $20 which she handed to him. I gave them my cash, except for $10 which I used to take a cab back to the hotel. Amy was calling after me as I was getting into the taxi, but I ignored her. As the cab drove by, Amy was yelling at her friend and talking on her mobile phone at the same time.”

My conversationalist laughed, rather inebriated, as he finished his tale, “Now I ask you, were they prostitutes or just interested in having a good time with somebody from the West?”

Business of Shanghai

I met several other foreigners who were in Shanghai for business. They all complained about how hard they had to work. Standing in line with me for the breakfast buffet was a woman from Kansas who worked for Hallmark Cards. This was her second visit to Shanghai but she had not seen anything of the city as she had to work everyday “until 9 in the evening”. A businessman from Bangladesh was on the same city tour which I took, his first opportunity in three trips here. An Israeli who sold textile machines took time off from exhibiting in a show -mostly, it seemed, to complain to me, and anyone else who would hear, about how hard it was to work with the Chinese: “They continue to bargain even after reaching an agreement with you.”

I sat next to Charlie on my flight to Beijing, and let him create the profile of a Shanghainese businessman in my imagination. Charlie was proficient in English and pleasant to talk to. He was going to Beijing on business. He was in his thirties. His father was a banker and his mother was a physician. They were not hurt in the Cultural Revolution “because we lived in a small town.” Charlie had worked six years for other businessmen and then, recently, formed his own partnership with two other persons. They were in “exporting auto parts.” International trade meant “exporting” to Charlie. If their venture in the auto parts did not work, Charlie said, he would get into exporting other goods. He rattled statistics which, if correct and relevant, would clearly assure his success.

Gallery Tiananmen

I walked toward Tiananmen Square with a sense of awe for its historical grandeur, and promptly fell into an amateurish marketing trap. On the wide sidewalk leading to the plaza, Candy and her friend May told me that they were art students from a college in Xian and if I bought a painting from the government gallery at Tiananmen which exhibited their works they would get one month free instruction from their art teacher. I agreed to go to the gallery with them as this late in the day the Tiananmen monuments were closed.

On the way Candy told me about her parents and sisters. Her father was a farmer and her mother sold the vegetable and fruit that he grew in his small lot. They gave away their first child, a daughter. Candy did not know where she was. Candy now had a younger sister. Because they lived in a rural area, her parents were exempt from government limitations on the number of children; they self-limited after three attempts did not produce a boy. “What do you think of Chairman Mao? Do you like him?,” I asked Candy. We were now standing under Mao’s giant face at the Gate of Heavenly Peace, where two couples were posing stiffly for a photographer. Candy looked baffled. “Of course,” she answered as though mine was the silliest question.

Candy referred to Xian as “the Chinese Midwest”. She said, “all kids in our school in Xian are given English names.” Candy said she learned English mostly by listening to special government radio broadcasts. In the gallery I met their art teacher. He was wearing a baseball cap that said “District Attorney, East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana” in a circle around a judicial scale logo. “This was given to me by Edward, my friend, the famous lawyer,” the teacher explained. By sheer coincidence, the following morning, on the hotel television screen I first saw the devastation that the hurricane Katrina was causing in that Parish.

I bought my first Chinese calligraphy painting from that gallery in Tiananmen Square. The currency note I could give them was more than the price and they did not have change. They gave me another painting instead, at a discounted rate. I was left to worry twice about carrying paintings on the remaining many miles of my trip.

Beijing Tourist

Mao’s Mausoleum. In Tiananmen, the next day I was surprised to see that the line at the Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum was short. No sooner had I joined it, however, than a man shouted, “No bag!” as he tapped my backpack. He grabbed me and wanted to drag me somewhere. He was not uniformed and I refused. Instead, I walked in the direction that he pointed to, but I soon returned as I could not find any place that would take bags. Now I saw the same man holding onto a European fellow and running with him across the hazardous traffic of the wide boulevard on the side of the Mausoleum plaza. I followed them and at a distance noted the place they had gone to. Then I saw them running back to the Mausoleum. That place, I realized, was where you checked your bags. By the time I got there, however, they had stopped taking any more. That European fellow was their last customer for the day. I missed seeing the embalmed Chairman.

Opera House. I went to the old Beijing Opera house where the Mao’s favorite, the Monkey King, was to be performed. The audience was mostly Western tourists; the Chinese themselves did not care enough for traditional operas to pay the considerable admission fee. I was seated at a table which I shared with a party of three. I was served a portion of watermelon, nuts, dried cherries, and one cookie. Ice cream and beer were available at an additional cost, as was an audio recording in English to guide you through the performance. I rented one. It broke down several times. The usher finally gave me a new one. Then I discovered that way up above the stage, there were supertitles in English which proved much more helpful.

They performed two shorts operas. I was surprised at how much I enjoyed them as this was my first exposure to the genre. I could not find the names of the operas, however, as there was no program. I asked the usher. She did not know, but she dialed a number on her mobile phone and handed it to me. The voice on the other end spoke sophisticated, albeit accented English. He introduced himself as the Director of the Opera House and told me that I had just seen the Monkey King. I had read enough about that opera, however, to tell him that the story line was different. He paused, told me to wait, and then apologetically corrected himself and said tonight’s performance had been changed to two other operas.

Temple of Heaven Park. I took a taxi to go to the Temple of Heaven Park. At the first intersection, while we were waiting for the red light to change, the driver opened the door and spit out on the street. This was a first for me, but not the last. Almost all of the other cabbies I rode with in Beijing repeated this defiance of the Chairman’s famous decree.

At the Park, a young Swedish girl asked if I could take her picture, handing me her camera. All of 20 years old, she was traveling alone, had come on the Trans-Siberian train, and was going to Tibet if she could obtain the rare permit from the Chinese authorities. She had a cold and was taking a pill that the drug store had given her. She showed it to me, asking if I knew anything about it. It was Contact, and I told her it was not harmful. I admired her courage, while I also feared for her innocence.

Outside the Park I saw a small food shop with several tables where the customers looked obviously local. I wanted some dumplings. The smallest order was a plate of 8. They were good but a bit bland. A hunchback who was sharing my table pushed a bottle of vinegar my way. It tipped and the content soiled my backpack. Back at my hotel, a motherly American lady told me that she used vinegar to remove other smells, but that she did not know what could remove vinegar’s smell. For days to come that smell on my backpack would remind me of the hunchback of the Temple of Heaven.

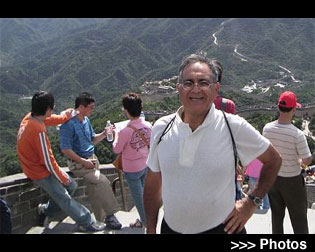

Great Wall. It was hot on the bus that took us to the Great Wall. The heat did not prevent two Chinese women and a man from vigorously working out at the elaborate gym facilities which were planted right on the sidewalks of Beijing. As I watched them perspire, through the window of the bus, what felt natural to me was to slip my feet out of my dock shoes. “Put your shoes on,” the tour guide gently chided me. I was put off guard so much that I did not ask what particular Chinese protocol I was breaching.

I was not the only misbehaving passenger on that bus. The guide quoted for us Chairman Mao’s saying that “a person is not a man till he climbs the Great Wall”. Ignoring this, one fellow tourist refused her friends’ pleadings to go with them and climb the wall; she stayed in the parking lot, saying “I was here two years ago, and the last I heard the Wall had not changed.” An Egyptian man violated the spirit of Mao’s command; he chain- smoked as he climbed the Wall all the way to the top, even though he was seriously overweight. It also seemed that far fewer Chinese than foreigners were doing the heavy lifting required by the Great Wall; they amused themselves instead by viewing a small zoo of black bears curiously maintained at its feet.

Traditional Clinic. We stopped at a traditional Chinese medicine clinic. Chairman Mao had been treated by the doctors in this clinic and his pictures were on all the walls. When they asked for volunteers to demonstrate their examination of patients, I offered myself as I happened to be sitting in the front row of the room. The doctor asked questions about my age, cholesterol count, blood pressure, and the frequency of my visit to the restroom. Then he took my pulse on both wrists. His diagnoses would have worried me if I had not been checked by my regular doctor just a few weeks earlier. I was given a prescription for herbal medicine that would have cost $300, a substantial sum in China. They said they would be glad to fill my prescription on the premises.

American Outpost

Xian is the Western outpost of American tourists in China. There are many attractions in this city that was China’s capital for many centuries, but the Americans congregated at the big tomb of the thousands of Terracotta soldiers -- more exactly, in the cafeteria of this place. That was the case, at least, on the day I visited it. I saw so many big men and women in shorts and polo shirts talking aloud with a thick East Coast accent in that eatery that I felt misplaced; they brought back memories of my trips to the crowded cafeteria in the famous Bear Mountain Park near New York City.

There were no other Americans in evidence on the rest of my journey to the western borders of China, a tour of the old Silk Road which now began. The exceptions were the three from Arizona in our group of 13 adventuring tourists. One of these lost her purse on the streets of Xian. This inauspicious beginning, however, had a happy ending. After returning to the U.S., she received an email from a Chinese student, asking her how best he could send her the purse which he had found.

Haggling

The Xian Museum displayed a good introduction of what lay ahead of us. It also provided me with the experience of mixing shopping in today’s China and the old-style Asian haggling. The Museum’s gift shop had an exquisite replica of a Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.) gem: a pottery camel with five musicians riding on it while playing their various instruments. The asking price, however, was too high and the piece was too big and fragile for transport. This was, however, the singular souvenir of the journey which I was hoping to find, so emblematic of the Silk Road as the ancient highway of peaceable globalization. Fortunately, my problem was mitigated when the salesclerk cheerfully informed me that the Museum would ship the piece. The price still remained a hurdle. We negotiated but reached a stalemate. I boarded the tour bus and we were about to leave when the salesgirl ran into the parking lot and climbed the bus to announced a new price authorized by the director of the Museum, who had now become personally involved. The offer was not good enough even for a counter. Later in the day, however, I regretted my refusal. I used our local guide’s assistance to deliver my counter offer. It was rejected, and we left Xian.

Several days later, after a futile survey of alternative souvenirs, I sent an email message to the guide in Xian to declare that I would accept the last offer by the Museum. She responded that the salesclerk was now saying that the Director had reprimanded her for their offer as he thought it was too low, considering the risk of breakage in shipping such a fragile item. The negotiations, however, were not terminated. If I agreed to pay a certain additional sum, the guide continued, the Museum would deliver the Camel. I recalled the Israeli businessmen I had met in Shanghai. I emailed my capitulation. I am still waiting to hear from Xian.

Portal to the Muslim World

Xian is China’s doorway to its western, Muslim, neighbors. We had our main meal at a Muslim restaurant, visited Xian’s colorful Muslim bazaar, and went to its big Mosque where we were formally received by the assistant to the Imam, the leader of Xian’s 60,000 strong Muslim community. He told me that he had just come back from a visit to Iran. A Persian stone tablet in the mosque, probably from the 14th Century, testified to the ancient ties. The Persian words still current among the Xian Muslims were clues to the origin and reasons for those ties: bamdad (morning), and sham (evening) -used especially in reference to the times of Muslim prayer-, doosti (friendship), doshman (enemy), and khoda hafez (goodbye). The walls of the huge main prayer room of the Mosque had wood panels with the Arabic verses from the Koran inscribed in small letters. I had never seen such remarkable display of what could well be the whole of the holy book.

Horse on the Train

The train station in Xian was dimly lit as we hauled our luggage up and down many steps that night. “The porters could not be trusted,” our tour guide explained, “they stole clothes from some tourists’ bags last week.” We were divided into groups of four on this night train to Lanzhou. There were four beds, two each on the top and bottom. We were still strangers and this was our first opportunity to “bond”. One man set up his Ipod with its speakers, another opened a bottle of Scotch Single Malt and the third began a story about his son, while we drank the liquor from our emptied water bottles. Soon the door to our car was opened and we saw a thin Chinese man grinning at the threshold. “Can I join you?” he asked. Before we could answer, he asked again: “Where are you from?” He continued without a pause, “I know where you are from is beautiful.” By now he was sitting on one of the beds.

We welcomed him, albeit reluctantly. He said his English name was Horse. He told us that he was a graduate of the Xian Technical School and worked as a “network engineer” in Lanzhou. His English did not enable him to follow our conversation which we had decided to resume. However, he would interrupt us repeatedly by initiating comments and questions on other subjects. He stayed in our car for quite some time.

Humor as Protest

Our guide in Lanzhou, David, was a study in the use of humor as a safe means to protest under an authoritarian regime. “Our politicians in Beijing like to do Tai Chi,” he said. Demonstrating, he moved his body following both stretched hands to one side as though throwing something out: “not my responsibility,” he said, pretending to be the imaginary politicians. Then he reversed the motions of the body and hands to the other side: “not my fault.” We laughed. Cleverly, he did a balancing hedge. Pointing to the constant mist and fog of Lanzhou which is the center of Chinese nuclear weapons research, David said “the CIA’s sophisticated aerial surveillance has concluded that these consist of umbrellas that China has put up to conceal its research facilities.” Another laugh, this time at the expense of foreigners, allowed David to come back to his domestic subject. He told the story of a farmer with a donkey who was being taught by the police not to cross the intersection when the light was red. At this very time, however, some military vehicles drove by and blatantly ignored that traffic rule. The farmer now admonished his disobedient donkey: “Why are you crossing while the light is red. Are you the military?” David would later explain, “You see no soldiers on the streets in China. They are called armed police.”

Inevitable Accident

David’s territory included the sensitive areas of “Minorities” in China, and it was on the way to their domain that he used the metaphor of suppression. “We need machine guns,” he said. However, he was not referring to the Minorities; his targets were drivers in an accident that delayed us for more than two hours. The highway that connects Lanzhou, a transportation hub, to points south is important for commerce and it was crowded with trucks as well as buses and cars. Only a narrow two way road, it looked neglected compared to the numerous superhighways that ring Beijing to facilitate the “politicians” commute. Long stretches of this road were under construction, not to expand it but to rectify a mistake in the original construction that neglected to provide for adequate drainage. As a result, in many places the road was reduced to one lane, with a big hole dug on the other, where pipes were being laid. Opposing traffic had to take turns at these points, which was unappealing to many impatient drivers. Their game of chicken finally produced a head-on collision between a truck and a bus near the town of Linxia. Traffic backed up on both sides, with vehicles parking on every inch of the both lanes, while police, insurance adjusters, mechanics were called.

Despite David’s cynical expectations, no fight broke out. In fact, a carnival atmosphere emerged in the beautiful green countryside with the hills in the distance. Curious cows crossed the shoulders to mingle with us. There were so many idle people around that a French tourist suggested that shovels be brought so that we could manually fill the hole in the lane next to the accident to enable passage. As with so many ideas from France this sounded good in theory but evidently no Chinese in charge thought it would really work.

Minorities

“Their features are almost the same as the Hans; the only difference is their religion,” David said in reference to the Chinese Muslims who are the majority population of the Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture. In fact, these Muslims compromised several “Chinese Minorities”: Hui, Dongxiang, Baoan, and Salar. To our untrained eyes, however, both they and the “Chinese Minority” Tibetans were distinguishable from the Hans (“non-Minority” Chinese) not physically but by their clothes, foods, and the architecture of their buildings. In Linxia I bought a rimless hat of the type the locals wore -which allow the Muslims to touch the ground with their forehead as they pray- and my first flat bread made in an open oven of the type found in Central Asia. We also had our first taste of noodles with spices distinct from those customarily associated with “Chinese food.” Both here and in the town of Quanghe we saw numerous mosques.

An elaborate gate on the road physically separated this Muslim Prefecture from the neighboring Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. On the other side, the hilly road rose from the valley steadily to the Labrang Monastery at about 10,000 feet. There were other Buddhist temples and buildings along the road, but they were dwarfed by this lamasery. We stayed at the nearby hotel with its bare rooms and virtually no heat or hot water, and woke up at 4:30 to witness the monks’ procession to their morning meditation in the great hall. Starting at 5:10 they came individually and in small groups from all directions. Their fuchsia color robes almost touched the ground. Some wore special hats. They sat in rows on cushions. The leader was in the center with the light focused on him. They chanted. After twenty minutes we were motioned to leave, because the main event was over. In all, this was colorful and uplifting.

Outside we saw two women who walked fast circling the main hall several times, in a devotional exercise. Slowly, the sun came out. The scenery was superb, but I suspect it was the mystique of “Tibet” that caused our group to stay around and take so many pictures. We realized we had reached saturation when we found ourselves photographing each other taking pictures. Then we went to a store that sold souvenir trinkets not any more authentic than you could find in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. I had no choice but to go along with the group’s wish. I felt cold; I was bored and I could not conceal it; my expressions annoyed avid shoppers in our group.

Yellow River Buddhas

In our short time in Lanzhou we also squeezed in a visit to the Binglingsi Thousand Buddha Caves. To get there, after a long bus ride, we sailed on the boat upstream on the Yellow River. We landed at the entrance to the caves in the middle of magnificent huge red rocks -only the carved Buddhas were more impressive. We were greeted by women peddlers who swung their beads and textiles before our eyes while saying “you come back”, the sole marketing slogan they had learned.

Middle Kingdom

David was an exceptional guide. I especially liked his enterprising spirit. He knew a lot about digital photography which he had put to good use. He showed me the marvelous collection of pictures of children which he had just had printed. He would show them also to his many contacts along our tour road. He had been in the tour business for more than ten years, accommodating different employers. He held two jobs; the other was with an adoption agency. I took him to exemplify those who were now shaping China. Once, as we were waiting for others to board the bus, I was showing him my pictures of Tiananmen Square which was dominated by Mao’s visage. I asked, “Why haven’t I seen any sign of him in Lanzhou?” David said nothing, but led me to the other side of the street and pointed at the Statute of the Chairman at the intersection which I had missed. “Is he popular?” I persisted. David smiled, “Mao is seventy-thirty; seventy percent good and thirty percent bad.” Then David hedged, characteristically, “That is what people say about him here.” David wanted to avoid attribution. On the map of China, Lanzhou is close to the center. I was willing to accept that assessment of Mao, and the Communist regime which he represented, as the view of “middle China”.

Toll of the Trip Toll of the Trip

The pace of our tour had exhausted most of us by the time we took the plane out of Lanzhou that night, at 10:30. In the past three days we had been in the bus driving on roads full of potholes for more than 10 hours a day, having slept on the train or in uncomfortable beds for no more than 5 hours a night. When we landed in Dunhuang, it was past midnight. Very few lights were on in the airport and in the confusion, our new guide missed my bag when he delivered our luggage to the hotel. My anxiety that someone might have taken it was real that night, even if unfounded, since the bag was still in the airport the next morning.

Dunhuangology

The landscape in Dunhuang was dramatically different from what I had seen thus far in China. This was a desert and a beautiful one at that, claimed to be the most scenic in all of the Silk Road. It was easy to accept that local boast as I rode a two-hump camel, for fun, on the yellow sand dunes just outside the town toward the small Lake of the Crescent Moon. This was my first such ride, even though as a child in my hometown I had seen camels used routinely for delivering goods.

Buddhism was brought to China from Central Asia via the Silk Road by travelers on the camel’s back. Their legacy was spectacularly recorded in Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. There I saw old wall-paintings which combined Chinese styles with influences from Persia and India, still in vibrant colors. These and equally precious statues, created over a millennium from the 4th Century onward, constituted a truly unique art gallery in the desert. Our docent was, appropriately, a research associate at the Dunhuang Research Academy, which is dedicated to “Dunhuangology,” or the study of not only these art works but also volumes of religious texts and many manuscripts found here on history, economics, medicine, literature, and customs. The guide took us to Cave 17 where these remarkable documents had been found in the late 19th Century. She informed us that the manuscripts were in many languages. I told her of my special interest in the Sogdian texts, as they could illuminate the crucial link that the Sogdians, an ancient Iranian people of Central Asia, played in connecting China and India. She took me to her office and I met her associates. We agreed to stay in touch.

That afternoon, we drove from Dunhuang to the hamlet of Liuyuam to catch the train to Turpin. The local grocery store was surprisingly well-stocked with the provisions we sought for our overnight trip. The train station was overcrowded, and everyone was talking at the loudest decibel. Station agents had to make their announcements with a hand-held bullhorn, yet they were barely audible over the cacophony. We rode that night parallel to the imposing shadow of the distant Altai Mountains.

Chinese Turkestan

When we arrived in Turpan at dawn, we were met by another striking sight: many people were lying on blankets spread on the street before the station, waiting to board the next train. Very few of these looked Chinese. We were now in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region where the dominant group was the Turkic Uygurs with physical features distinct from the Han Chinese. In the West, when I heard about the Chinese “Muslim problem” the reference was usually to Xinjiang. Historically a part of Turkestan which extended to the Caspian Sea, this had been the region of China most exposed to influences from Islamic and Persian and civilizations.

When the bus that took us from the train station arrived at our hotel, I read its name inscribed in Persian at the entrance: Boostan Mehmankhaneh (The Garden Hotel). The long pedestrian mall that connected the hotel to the center of town was covered by a grapevine-wrapped trellis, creating a Middle Eastern ambiance. Around the mall store names, many of them Persian, were written in Arabic script. That evening we went to a concert of folkloric music in an outdoor setting which transported me, in imagination, to Turkey.

The most prominent building in Turpan, the Emin Minaret, was built by a Uygur ruler in the 1770s. In the Mosque which was next to the Minaret, I met a venerable looking Muslim Imam and his entourage. They all wore white. They responded warmly when I greeted them, “Assalam aleikum.” In the outskirts of Turpan we visited its other major attraction, the irrigation system of karez. A succession of wells connected by underground channels which used gravity to bring water from high elevations, karez (a Persian word, interchangeable with qanat) was an example of Persian technology, long ago transferred to China via the Silk Road.

“Turpan Expeditions” from Europe in the 20th Century, unearthed ancient manuscripts in the ruins of the city of Gaochang, a few miles from Turpan, which revolutionized oriental, religious, linguistic, and literary studies. Among them were the only extant Manichaean scriptures, illuminating our knowledge about that long lost Persian religion, and revealing the exodus of the followers of Mani, the ancient Persian prophet who challenged the official creed Zoroastrianism. To explore the dusty remains of Gaochang, we joined the local tourists and rode a donkey-driven cart. This frolicking atmosphere was accentuated by the presence of souvenir vendors with their colorful goods. The one who engaged me, communicated her prices by writing the numbers on the palm of her hand. It was from a shop at an opening to the karez, however, that I bought a documentary relic of contemporary China: a 1960s poster showing Mao and his lieutenants -including the then favorite Lin Piao- all waiving his Red Book.

When we went to the nearby Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves, we met the more serious Japanese tourists. They had come in search of their own heritage, the ancient traces of Japanese Buddhism as transmitted from Central Asia. The murals of these caves survived in rich and fresh colors to tell the history of a thousand years. In the 20th Century, however, European explorers cut up and removed the best of them to museums in their own countries. The ones they left had long been subjected to desecration by the local Muslim fanatics who considered them symbols of idolatry. In China one often hears about the intentional destruction of cultural monuments by the Red Guard. In that, they were not original.

Colonial Seat

We drove by bus from Turpan to Urumqi on a road that passed through pristine pastures before the majestic Heavenly Mountains. We saw many windmills, indication that we were approaching a much more modern city. Urumqi was established by China in 1762. It was first called Dihua, meaning “to enlighten and civilize,” which was the Chinese attitude toward the local population. Today, it continues to be the capital of Xinjiang and it is still largely populated by the Hans. The picturesque parts of this big city, however, are its Uygur markets, like the Erado Qiao which we visited. A new feature for us here was the outdoor Shashlik cafes, the evidence of years of Russian influence in this bordering part of Xinjiang. I climbed the tower in the middle of the market. In the circular room on the top, the walls were covered with pictures of government officials from Beijing.

We went to the Urumqi Museum because one member of our group was intrigued by reports that it had ancient blonde and blue-eyed corpses in its collection. He was from Scotland and speculated that the corpses might be from his homeland -many were looking for traces of their heritage on this trip. There were indeed several well-preserved ancient corpses in the Museum, but each had been identified to be from a specific local ethnic people.

The Museum had other ancient artifacts described in English and Cyrillic. One was a vase tagged with its Uygur name, ghadah kuzeh (pottery vase). I read it loud. Two steps away, a woman and a child were squatting, eating watermelon seeds. The woman was surprised that I could pronounce those Persian words. She now volunteered to show us the museum. We learned that she was, in fact, the museum guide, having come from Shanghai only a month before. She gave me her two email addresses to send the pictures we took with her. Both included the number 5. I asked why. She said the number referred to her family of two parents and their three children. Once again, the vaunted Chinese population control rules showed us a loophole.

Our Guide Sarah

Our national tour guide in China, Sarah, was a Han who lived in Urumqi. She disliked her job. It took her away from home on difficult trips throughout China. She was paid only $12.5 a day. Sarah was diligent, efficient and courteous, but she did not have the ebullient personality required to please foreign visitors. China’s vibrancy dissipated in her presentation. She had been at this job for five year and she was burned out. Sarah told me that next year she would try to get a job teaching school, like her mother. I wondered if she did not reflect the ennui of the larger Han community of Urumqi who were transposed upon the Uygurs of Xinjiang to guard China’s far away western frontiers.

Sarah’s one big mistake was failing to screen the hotel chosen for us in Kashgar by the local guide. As we arrived in the lobby late at night, we were greeted by a man in his pajamas who, we later learned, was the manager. The soiled carpet here was partly covered by a long white rag; its dirt and tear were more exposed in the corridors of the second floor where my room was. There was no water in the toilet but the plumbing leaked elsewhere in my bathroom. We were served breakfast in a hall which had an empty frame for a missing television screen, affixed to the upper corner of a wall. Sarah responded to protests from many in the group by hastily arranging a move to another hotel the next morning -designated for foreigners, she explained, unlike the previous hotel which was for Chinese tourists. A row of four receptionists welcomed us at the entrance to this hotel which had a newly carpeted lobby and “three star bathrooms”. Sarah’s one big mistake was failing to screen the hotel chosen for us in Kashgar by the local guide. As we arrived in the lobby late at night, we were greeted by a man in his pajamas who, we later learned, was the manager. The soiled carpet here was partly covered by a long white rag; its dirt and tear were more exposed in the corridors of the second floor where my room was. There was no water in the toilet but the plumbing leaked elsewhere in my bathroom. We were served breakfast in a hall which had an empty frame for a missing television screen, affixed to the upper corner of a wall. Sarah responded to protests from many in the group by hastily arranging a move to another hotel the next morning -designated for foreigners, she explained, unlike the previous hotel which was for Chinese tourists. A row of four receptionists welcomed us at the entrance to this hotel which had a newly carpeted lobby and “three star bathrooms”.

Kashgar

The government buildings that the Chinese Communists had built encircle Kashgar. Inside, it is a medieval town of riotous colors. I sat in the front seat of a taxi as it maneuvered through men, animals, and a wide assortment of vehicles toward the covered bazaar. Along the way we passed mosques and minarets of different vintages, representing the many phases of the history of this city which was first mentioned in Persian documents of some 2000 years ago.

The main bazaar was the town’s regular marketplace for all kinds of goods. We also had the special treat of visiting the weekly Sunday Bazaar on its own separate grounds. I passed through rows of watermelons which the local farmers had brought to sell], and came upon cobblers who were repairing shoes while their customers waited barefoot. There were food stalls exuding exotic aromas. Behind them, the sheep for sale were arranged in double lines, creating the illusion that they had their heads screwed on backwards. You could also buy cows here. The most animated scene, however, was where the horses were. Here I saw three customers testing their choices by galloping them up and down the field.

Kashgar’s Idkah Mosque is the largest in China with the capacity for 10,000 worshipers. Only a few were there on the day I visited it. Our Muslim guide said he prayed in a mosque only once a day. He was not particularly knowledgeable about his religion; he said that in praying he faced the prophet’s tomb but he was corrected as the orientation is instead toward the rock of Kaaba in Mecca. Idkah is a Sunni Mosque but its only elegant furnishing was a carpet from the Shiite President of Iran who visited in the 1980s. Kashgar’s Idkah Mosque is the largest in China with the capacity for 10,000 worshipers. Only a few were there on the day I visited it. Our Muslim guide said he prayed in a mosque only once a day. He was not particularly knowledgeable about his religion; he said that in praying he faced the prophet’s tomb but he was corrected as the orientation is instead toward the rock of Kaaba in Mecca. Idkah is a Sunni Mosque but its only elegant furnishing was a carpet from the Shiite President of Iran who visited in the 1980s.

I could picture joyous celebrations in the beautiful space that was the plaza before the Mosque. Idkah was a most appropriate name as it meant a place for festivities in Persian. The alleys around the Idkah were jammed with traditional shops. There were silversmiths, haberdashers, tea shops and shashlik stands. I walked into a store that sold local musical instruments. A man in his forties was playing the kamanche, an ancient Persian string instrument. I sat next to him, listening. The piece was Beethoven’s Fur Elize, unexpected in that setting but very soothing. He told me that he was a fifth generation kamanche maker.

For dinner we went to Chini Bagh, once a famous center of international intrigues. It was the residence of British India’s representative in Kashgar during the Great Game rivalry with the Tsarist Russia in the 19th century. A most charming building and evocative of nostalgia for British visitors who flocked there, Chini Bagh now seemed totally out of place. It was flanked on one side by the crumbling mud houses of the oldest district of town and on the other side by a plaza hosting one of the biggest statutes of Mao I had seen in China -at a height of 60 feet.

Passage Out

Historically, Kashgar’s raison d’etre was its location near the gaps on the high Pamir Mountains which allowed passage between China and its neighbors in Central Asia. Early on the morning of my last day in China, we boarded our bus to go to the Irkeshtam Pass at the border with Kyrgyzstan. As we climbed the steep road, the temperature dropped. We stopped at a road-stand and bought bread for breakfast. It now began to drizzle. The potholes were getting bigger too, and we felt the discomfort of our aging vehicle even more. Suddenly we came to a full stop. A police car had blocked the road, and beyond it we saw an idle construction truck. A stream was running over the road. It was hard to tell if this was a runoff of the current light rain.

We had no choice but to wait, but we were getting anxious because there was only a window of a few hours for crossing the pass. We had been told that much advance planning had been required to synchronize the brief times that the border offices of these two countries at this pass would both be open. When the truck driver resumed work we sped to the frontier and reached the Chinese customs and immigration offices at 8523 feet above the sea. We were processed with deliberate speed. Now we had to make arrangements to cross the long “no-man’s-land” which was the distance to the Kyrgyz border. At first we were told that a Chinese official vehicle would take us. Eventually, however, a Chinese Officer boarded our bus and we started off.

We drove slowly through one mile of desolate space. At the end of it there were some structures that housed the Chinese observation post. When our bus stopped we were told that our Kyrgyz guide was on his way to meet us. Our luggage was unloaded. Our Chinese guides were apologetic because they now had to go back with the Officer in their bus. We were no longer their charge, but they departed reluctantly as there was no sign of our Kyrgyz guide. We were left standing with our luggage in the cold barren land, facing the Kyrgyz border guards who looked very young with their big weapons hung on their shoulders. We did not speak their language and they spoke very little of ours.

About

Keyvan Tabari is an international lawyer in San Francisco. He holds a PhD and a JD, and has taught at Colby College, the University of Colorado, and the University of Tehran. The information contained in this article may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or otherwise distributed without the prior written authorization of Keyvan Tabari.

|