On the night of the 14th of July 1789 nothing out of the ordinary was going on in Iranian politics. Agha Mohammad Khan Ghajar, still a few years away from the Persian throne was locked in conflict with Lotf Ali Khan Zand, still a few years away from being betrayed, blinded and choked. Same old same old! The real action that night in July was happening a few thousand miles to the north, in Versailles.

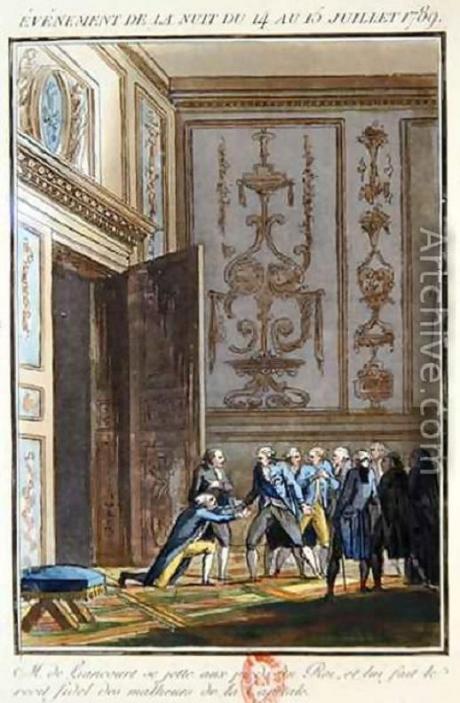

There, Duke Rochefoucauld-Liancourt hastily entered the palace of Louis 16th of France, bowed, and reported that the Bastille prison had been stormed by the people of Paris. Still not blockbuster material for historical action dramas. Stuffing a handkerchief down Lotf Ali Khan’s throat with a stick would be a bigger box office draw. The French drama won the 1789 Oscar less for the action than for the dialog. “Is this a revolt?” Louis asked, to which the duke replied, “No Sir, this is a revolution.” With this repartee Liancourt sent the word “revolution” on its way to acquiring its modern political meaning.

The king saw the Bastille event as a defiance of authority, something his soldiers or even reformed policies could try to deal with. Liancourt on the other hand was thinking in terms of historic inevitability. He was saying there was nothing any king could do, no matter how powerful or how smart he was.

To be sure, in scientific circles the word “revolution” already did have connotations of inevitability. The planets revolved around the Sun in an orderly manner, and inevitably returned to their starting point, i.e. in one revolution. Putting History in its own celestial sphere, thinkers could glimpse the idea that greater laws of social origin trumped the laws of kings. Even the French saw their goal as a return to a romanticized version of Roman and Greek societies. We also see this in Farsi word enghelaab, which means, “return” or “turning over.” But Liancourt ‘s use of “revolution” signaled a progression of understandings until the word no longer means an inevitable and irresistible return to the origin. Nowadays “revolution” implies irreversible upheaval into something totally new, as in industrial revolution, or digital revolution.

In this modern sense, Iran’s 1906 revolution is properly named, as it tried to establish an order never before experienced by the nation. In the antique sense, the accession of the Pahlavi dynasty was a revolution too, though it is never called that. It was a cycling back to Iran’s old system of governance, and nominally did strive towards a romanticized version of a glorious past. The 1979 revolution, however, is not properly named in the modern context. There was only a superficial change from a monarchial form of absolutism, not too unfamiliar with handkerchiefs and sticks, to a theocratic order similarly comfortable with rapes and hangings. In this upheaval of 2010 the Supreme Leader is about to ask, “Is this a revolt?” The participants in the storming of Evin or Kahrizak, should make sure that Liancourt can confidently reply “Non Sire, c’est une enghelaab.”