|

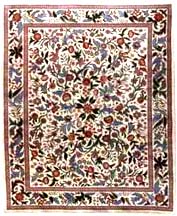

Words WordsWhen you were little you were ashamed when I came to your school By Sepideh November 27, 2002 The Iranian I'm a sophomore majoring in creative writing and minoring in advertising at University of Southern California in Los Angeles. I recently wrote a series of monologues about being Iranian-American for my American literature class. I've submitted one of them below. It's written by me, but from the point of view of the immigrant mother who struggles with the cultural assimilation of the child she is speaking to. If you want to know more about me, you can check out my website. Americans. They don't understand our subtleties. You bring your friends here and they wear their shoes in our home. I don't care if you wear your shoes when you go there: they don't have rugs older than your grandmother under their feet at their houses. It doesn't matter if I say, "Welcome, be comfortable." No one says, "Take off your filthy shoes which you tracked in mud and dirt before you came in my clean house, where I am going to feed you and serve you." These are things that guests should know. They are rude to say. You are becoming like them. I am worried about you. Don't argue with me. You are becoming like them. Yesterday when I pointed out that kaseef girl by your school, that dirty girl in the short skirt. She was dressed like a prostitute, but you just said "Whatever, Mom." You think it is okay to stand at a corner in a skirt like that? And you think I don't understand you when you talk with your friends. I do. I speak English too. Maybe I have a bad accent, an accent that embarrasses you, but I am not stupid. I understand your words. But sometimes I do not understand their meaning. When you were little you were ashamed when I came to your school and the teacher said good things about you. I agreed and said, "She is my proud." I know I said that wrong: you are my pride. But you blushed and said, "That's WRONG, Mom." But you said it quietly, because you didn't want to embarrass me in front of your teacher. You were my good girl. I want you to be happy. Everything I do, it's for you. Before we came here, we lived without thinking every minute if everything we said and did had meaning. Here I have to explain to you that "khafesho" doesn't exactly mean "choke to death."  I

tried so hard. I even tried to help you join with your American friends in their

activities. I wanted the best for you. We went to their Girl Scouts and softball

and PTA meetings, but we only went once, and then you didn't want to go back. Why?

I was not like those women there; my English was not good, I know. But I was no less

than them. I loved my child as much as they did. It wasn't my fault if I didn't fit

in their dry culture. They didn't even smile at me. They didn't even say hello. When

Americans go abroad, they are treated like kings and queens. Not because they are

special, but because the rest of the world understands hospitality. Who are these

people who don't say hello when you go to their meetings? And then they look at you

funny when you try to show your child that you love her by being involved. I

tried so hard. I even tried to help you join with your American friends in their

activities. I wanted the best for you. We went to their Girl Scouts and softball

and PTA meetings, but we only went once, and then you didn't want to go back. Why?

I was not like those women there; my English was not good, I know. But I was no less

than them. I loved my child as much as they did. It wasn't my fault if I didn't fit

in their dry culture. They didn't even smile at me. They didn't even say hello. When

Americans go abroad, they are treated like kings and queens. Not because they are

special, but because the rest of the world understands hospitality. Who are these

people who don't say hello when you go to their meetings? And then they look at you

funny when you try to show your child that you love her by being involved. They looked at me like I was stupid, like you are looking at me now. But I wasn't. I had a degree. I spoke three languages, and was learning English as a fourth. How many languages did they speak? Look at me when I talk to you, please. Do not turn your back on me. Ghorbunet beram, azeezam: I would sacrifice myself for you, my dear. And I have. Does this article have spelling or other mistakes? Tell me to fix it.

|

|

Web design by Bcubed

Internet server Global Publishing Group