Father

and Fatherland

Father

and Fatherland

... in the poetry of Nima Yushij

By Majid Naficy

February 4, 1998

The Iranian

Related links

* Listen to Nima's

poetry on Neda Rayaneh's site

* THE IRANIAN Literature

section

* Bookstore

* Cover stories

* Who's

who

From

Majid Naficy's "Modernism

and Ideology in Persian Literature; A Return to Nature in the Poetry of

Nima Yushij" (University Press of America, 1997), pages 30-37:

From

Majid Naficy's "Modernism

and Ideology in Persian Literature; A Return to Nature in the Poetry of

Nima Yushij" (University Press of America, 1997), pages 30-37:

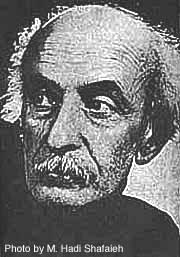

Nima Yushij was the pen name he used when he wanted to publish Afsaneh. His real name was Ali Esfandiari, and, as will be seen further on, as pseudonym, Nima Yushij, clearly shows his love and admiration for his father and his fatherland. In an autobiography which he wrote for the First Congress of Iranian Writers, which was held in Tehran by the Iranian-Soviet Cultural Relations Association in 1946, Nima subconsciously puts these two elements side by side:

In the year 1895, Ebrahim Nuri -- a brave and angry man -- was considered to have descended from an ancient village in the north of Iran. I am his eldest son. My father was preoccupied with his life in agriculture and shepherding in this district.

In the autumn of that year, when he was living in his summering grounds, Yush, I came into the world. My lineage on my mother's side, goes back to Georgian fugitives, who fled to this country long ago.

My early life was spent among herdsmen and horse breeders, who in search of meadows, migrate between distant summering and wintering grounds, and at night, get together for long hours around the campfire in the mountains.

From my whole childhood period I remember nothing but wild wrangles and things related to nomadic life and their simple recreation in monotonous, blind, and ignorant tranquility.

In the same village where I was born, I learned to read and write from the village mullah. He chased me through the garden alleys and tortured me ruthlessly. He tied my tender feet to the snarled and thorny stinging trees, beat me with a long stick and forced me to memorize letters which the village households usually write to each other, and he had attached them and had made a scroll for me.

Nima had a younger brother Ladbun, and two sisters named Nakta and Behjat. As can be seen from Nima's correspondence, the two brothers had a close relationship. Nima also wrote letters to Nakta and dedicated to her one of his early long poems, Khanevade-ye sarbaz (A Soldier's Family). Nevertheless, none of his siblings nor his mother had an impact on him that his father did. In a poem called Pedaram (My Father), which he wrote thirteen years after his father's death in 1926, he talks with nasim (the breeze) and sees in it his father's agility and cleverness:

Like you [the breeze], he on swift heels

Descended from this mountain peak

But following behind him

Were two lads fast and brave.

Then he remembers when his father returned home from his journey late at night and the family circled around him:

When [the father], the village darling, came to the village

Our hearts were in hope of finding his

The night was dark and the world had drowned

In the fearful silence of the village.

I saw a man armed

Drooping moustache, staff in hand,

A shadow of a smile on his lips every moment,

Coming towards us fatigued.

My mother jumped up and lit a light

He became a shadow, as if covered in tar,

Has he hitched the horse in the garden?

Has he jumped down from the wall?

Til dawn with wakeful eyes

There was talk of trouble on the journey

We were sitting all around him

He was gazing at our faces every moment.

He was asking after each of us

Sitting like a hero on the ground

Kind to all the world's people

His words cheerful, warm, and sweet.

Like you [the breeze], he went fast

He went and left me to grieve for

He hid his face from the world and shortened his journey

And I became worn with grief.

In the end he calls the breeze again and seeks in it his lost father:

My eyes are peeled to the road

I ask the road for him each moment

When you [the breeze] come to me tired,

I tell my dejected heart,

"I wish he would come through this window."

I shout out to him from afar, "Come!"

I would tell my wife Aliyeh, "Woman!

My father has come. Open the door."

In another poem that he wrote for his father two years later, called Panzdah sal gozasht (Fifteen Years Have Gone By), he draws his inspirations from his father's bravery and manliness and sees his own militancy as mirroring that of his father:

Fifteen years have gone by

Each day worse than a night

Each night turned blacker because of the black day.

Fifteen years have gone by

Since you left my side

I still have words of yours dangling from my ear

Oh, father, my eyes still

Attend to many of them.

Ah, why did you go like that!

Fifteen years have gone by

Each night one year and each day one month

But I did not come one bit short of my work.

I stood strong against the hardships

And thanks to loneliness

I did what I should have

And what I raised up

Got its beauty from your treasure

In a simple and at the same time beautiful poem called Az 'emarat-e pedaram (From My Father's Mansion) he first describes parts of his father's ruined house which still remained:

My father's mansion remains only in name

On the north side a hall

On the south side an archway

On its exterior the stables

Now the owl has nested in it

And a panel dangling in the doorway.

Then he sees a man who could be interpreted as either Nima or his dead father sitting in a lighted room of this house.

The door is open and his house is dark

Sometimes a lamp is lit in one room

A man has made his bed

His head is bent over a book

He has brought his knees to his chest

His hand is spinning over a notebook

Night, darkness, a lamp, and that man

In a tangle, but in the notebook

They have created another mansion

In the final stanza, the reader gets the idea that Nima finds his father incarnated him:

His hand wrote this on a page,

"My father's mansion remains only in name."

His soulless body has become like a body for me.

One month after Nima married Aliyeh Jahangir, his father died in May 1926. In a letter to his wife, he expressed his grief thus,

Last night out of terror I did not get to sleep until dawn. Who has seen such a coward, trembling like a willow. A half-dead flame, a heavenly book, and a piece of mud brick, in the corner of my father's room, have taken my father's place. Is a spirit conjured up by these means? Perhaps! My father! My father! Last night a black hand incessantly was pressing against my chest. Why don't they leave a lunatic even in the middle of the night! I took refuge to my mother out of fear. What a refuge! I started walking. My legs were trembling. The shadow of a boxwood bush startled me.

Here a hero has gone to sleep far away from home, and his body has gone cold.

Searching for a lost father is an ancient theme in literature, from Homer's Odyssey to James Joyce's Ulysses, which shows the longing of human beings for their origin and a sense of continuity. This search for one's ancestors, in turn, is linked with looking for one's birthplace, and here, history borders on geography, and love for father, or love for the fatherland.

A geographic dictionary of Iran prepared by the military, describes the village of Yush, thus,

The village is located in a valley. this valley runs from south to north starting from Mount Lovash, then from the village of Ilka, flanked by two low and high mountain ranges and continues until you get to Yush. Yush is the point of juncture and the valley bends eastward, toward Baladeh [...] In the valley is a river called Haraz, which is a generic name. Most of the land in the village is cultivated, especially near the dwellings, and it is these cultivated fields which connect the surrounding villages...

The land north of the river is called Khortab ("Sunny") and the southern Nesem ("shady"). The snow in the Khortab land melts sooner and its weather is warmer. The houses of Yush, and half of the cultivated fields, are located in Khortab, and on the Nesem side, there is not one building except one mill. The rest is all cultivated fields.

Nima was twelve years old when he was brought to the capital Tehran, and from the beginning he found himself a stranger among citydwellers. In his autobiography he goes on to say,

In the year, that I came to the city, my close relatives forced me and my younger brother, Ladbun, into a Catholic school. At that time this school in Tehran was known as The Higher School of St. Louis. My education started here. The first years of my life in school were passed wrangling with kids. The fact that I was withdrawn and shy, peculiar to children raised outside of town, made me subject to mockery at school. My art consisted of making a good jump and escaping from the school grounds with my friend Hosein Pezhman [who would later become a new-classical poet]. I did not do well at school. Only my grades in art [drawing and painting] helped me, but later on at school the care and encouragement of a good-tempered teacher, today's famous poet Nezam Vala, thrust me into writing poetry.

In his first long poem The Tale of Pallid Color/Cold Blood, he expresses his nostalgia for his village:

I am not one of these lowly people of the city

I am the painful memory of the mountain people

It was luck that brought me to your city

And I have been suffering ever since.

I am happy with mountain life

I've grown accustomed to it from childhood

Oh, how lovely is my homeland!

It is far from the reach of city folk.

There is no pretension there, no adornment.

No fetters, no cheating or treachery

How lovely is the fire on dark nights

Alongside the sheep on the hillside.

During his lifetime Nima always longed for his birthplace and on different occasions he expresses his admiration for the countryside and his disdain for the city and urban life. He called Tehran "the city of the dead." In an interesting letter that he wrote from Yush to his son in Tehran in 1959, a few months before Nima's death, the reader finds that, in spite of his age, Nima hunts, is familiar with the local terrain, and respects the villagers' opinions:

My dear son,

... In this separation and loneliness , it's obvious how sad your letter made me. On the other hand, I felt happy because Asadollah reached Yush one day later. I was deep in thought, why do you ask if I shot the rabbit or not? After your departure, I became listless that I didn't have the stamina to kill that beautiful and innocent animal. I barely made it to Kahriz.

I had my lunch there. They were harvesting wheat. All the time, many sparrows in this clear air that you know were singing in the trees. I was missing you and mamma. I lay down a bit in the sun, then I crossed the river. Surely you're thinking that I was out to hunt partridge, which I was mainly just hoping for that day of total anxiety to be over and for me to reach Yush before night fell. I wasn't blue just because even from faraway I couldn't hear the sound of partridges. In Aliabad, I ran into Bahadorkhan and others. I was sweating all over. I sat down a little and we chatted -- again for passing time. But the wind and the cold would make you desperate. Mount Nazar was still covered with clouds. The mountain could not be seen. You know when this mountain is covered with clouds, that means that it will be raining in the wintering grounds. It's getting colder in Yush. People gain experience. One should learn many things from people's experiences. It's not the books that make us knowledgeable.

About the author

Majid Naficy holds a doctorate in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures from the University of California, Los Angeles, and is currently co-editor of Daftarha-ye Shanbeh, a Persian literary journal published in Los Angeles, where he lives. His first collection of poems in Persian, called In the Tiger's Skin, was published in 1967. One year later his book of literary criticism, Poetry as a Structure, appeared. And in 1970 he wrote a children's book, The Secret of Words, which won a national award in Iran. He has recently prepared a collection of his poetry translated into English, called Muddy Shoes. (Back to article)

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved. May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

|

|

|