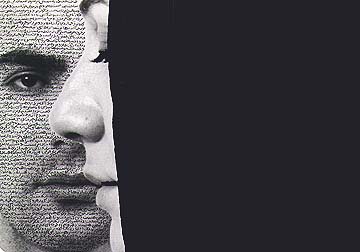

Photo by Shirin Neshat

The Rendez-vous

By Azadeh Naderi

March 12, 1998

The Iranain

When the woman woke up, she remembered it was July 14, 1986, and she had to keep a historic appointment. Her husband was up, and the sound of the water in the bathtub left no doubt of his location. Instead of the morning roosters and singing birds, Mahmoud was the herald of the new day. Familiar sounds followed one upon another: The slippers scraping against the floor; the opening of the bathroom door, razor and brush, toothpaste and cup, clattering out of the medicine chest. If she had had a few drinks the night before, or had finally overcome insomnia, or was sound asleep for some other reason, he still had other devices. He would clunk the kettle down on the stove, or call loudly to the kids. He would never shake her awake; politeness was still the order of the day. But one of his arrows would eventually hit the target.

She would walk-up with a headache, backache, toothache or stomach ache. Something was always the matter with her. She would leave the bed reluctantly. Her eyes half closed, she would search with her feet, near the bed, for her slippers, which Mahmoud had probably unwittingly kicked underneath. His carelessness would irritate her. She would throw herself on the floor, look under the bed, grumbling as she retrieved the slippers. She would put on a robe and go to the bathroom. She would put one on even in the summertime because her nightgowns were transparent, and she did not want her children to see that her nakedness did not interest their father.

While Mahmoud wrestled with kids, the woman prepared breakfast. She would put fruit and snacks in their lunch boxes, and sharpen their colored pencils, and be sure that they had erasers and notebooks. She would be sure that their socks matched, and their faces were washed before they left home. After they left, she would remain.

But not today. Today she would leave in a few hours to keep an appointment over the years she had occasionally thought of. On July 14, 1976, in a moment of love and ecstasy, she and a lover had promised to try to meet, and if they could not meet at least to think of one another and of the place. Now, although the woman was all but certain that only she would keep faith with the old pledge, she was determined to go.

But in fact, she herself would probably have forgotten the pledge if she had not lately gone to Naderi Street. She had dropped into the Naderi Cafe for a cup of coffee. As she pushed open the glass door, she asked herself, "What is it that I am supposed to remember?" At the table, waiting for the waiter to come round, she had done her best to lay hold of a dim intimation that seemed to want to come to consciousness. For as long as she could remember she had come to this hotel, with her parents, her friends, her lovers, and especially with the man, who liked this cafe. When the waiter put her Turkish coffee on the table, she remembered. And now this moment was reviving a familiar but obscure sense of openness to life.

Ten years ago after making love in the bachelor quarters of the young man, kissing and embracing among the scattered books, unwashed cups and glasses, and ashtrays filled with cigarette ends from the night before, after walking together in hot alleys, exchanging kisses, provoking in some onlookers admiration, in others disapproval, they chose the Naderi Hotel for lunch. The woman wore an orange tank top which showed to advantage her tanned, shapely shoulders. The man, tall, attractive and young, seemed to deserve such an attractive mate. All of the onlookers, whether approving or not, would have had to concede that the good-looking couple was well cast to play in this street show.

The garden restaurant of the hotel was swept clean and watered. Under the shadow of ancient elms, willows and cedars, rows of tables and chairs had been set out. The trunk of the trees, and the leaves of the ornamental shrubs, hid them from the sight of the parents and their children who had come to have lunch and dance. At the peak of noon an orchestra was about to play a tango; a blond couple stood under the shade of the marquee holding each other by the waist. The woman, hungry and thirsty after love-making and the walk in the hot streets, and waiting for the food to be brought, sipped her cold drink with childish delight. Everything was good. Nothing portended the revolution that, X years later, was to blight the pleasant trees and setting of the summer garden.

Today she put on the same orange tank top, but over it she put on the mandatory robe. She wore long black pants. She tied up her hair, and covered it with a navy blue scarf. Instead of summer sandals, she hid her toes in exercise shoes. She ran a chapstick across her lips. She knew she had changed, but everything else had changed, too. And the man, even if he did come, would expect something of the sort. No one expected to find a bare-headed lady in a cafe waiting the arrival of a man.

She wore dark glasses to cut the glare of the July sun. She took a cab to the Naderi Hotel.

***

The man walked to his car, then changed his mind, deciding to walk to the cafe as they had done ten years ago. He took off his light summer jacket, and carried it. He put on his dark glasses. The streets of Tehran were smoggy, smoky and hot. But to the man they were familiar, cozy and friendly. This was his city. He had wandered through these streets year after year. He knew the twists and turns of every alley and back alley. He had measured the length of them with his footsteps, had counted the bricks of their walls, and read all of the posters and slogans that appeared on them. He knew which street had a ditch on its left, and which did not, and which were dead ends even without a public notice. In the hot July noon the street vendors had collected their wares and gone to sleep in the shade of their cars. The odds-and-ends old men were napping in the shade, and the Ethereal Women in the court yards were stripping in their veils. The streets, sweaty and hot, were entirely his at this hour.

The Naderi Hotel, like the streets, was void of life and motion. The summer garden had been closed; the interior cafe was filled with sullen old men. Lunch was served in a partition of the interior cafe. The man wondered what had become of the garden with its cedars and elms? When he pushed the glass door open, he felt a cool breeze. He was standing in front of a large fan. He wished he could remain there, but a waiter in tail coat -- a relic of past glory -- ushered him to a table. Would the woman remember after all these years?

He sat in a corner and began reading his paper. To him, it seemed to be written in code. Some turbaned man had criticized some other turbaned men, and those who had been attacked had defended themselves in statements that themselves read like attacks. Mahmoud set his paper aside and looked at the door. Even if Azadeh did not remember, he was glad that he had come. Maybe it was even better that she had not come. When he saw her, he could not boast that only he had remembered their pledge, and offer it in evidence against her accusations of his coldness and indifference to her.

He looked into his heart, into his memory, the remnants of his emotions. Did he still love Azadeh? Azadeh who had seemed to be so beautiful, lively, and smart, now seemed faded, ordinary, and at times even boring, complaining about everything. Was it Azadeh who had changed, or Mahmoud, or both? Or maybe everything else as well.

The glass door opened, and Azadeh wearing a scarf and robe and sunglasses lifted her head and untamed face over many shoulders and heads. She saw Mahmoud, smiled, and came to the table. She said, "I can't believe you're here. Maybe I'd rather you had forgotten, so that I could celebrate the anniversary in silence and reflection."

Mahmoud said, "You see that I am here."

She sat down. "I can't believe you remembered."

"Maybe if you had not come to Naderi Hotel a few days ago I would not have remembered. But when you told me that you'd come, it suddenly came to me."

The woman asked, "Have you ordered?"

"Of course not," he said. "I was waiting for you."

"So you expected me to come."

"I don't know. I didn't think about it much. Maybe I too hoped you would not come, so that I would get a chance to complain about YOU."

Azadeh laughed. After a few seconds of silence, she asked conquestishly, "Have I changed a lot during the past ten years?"

Mahmoud sighed and shook his head. "I don't remember your face, but I remember you were wearing a red tank top, and that your hair fell on your shoulders."

"Orange," she said, "not red." In plain sight of the onlookers, she took off the navy blue scarf that covered her hair. Before the waiters and customers could return to whatever they were doing, she unbuttoned her robe, one button after the other, and took her hands and arms out of its sleeves; the worn tank top showed beneath her robe. She raised her bare arms and loosed the knot that held her hair in place. The hair fell to her bare shoulders. And before the staff of the hotel, the avid onlookers, and the Revolutionary Guards could intervene, she said, laughing, "I'm wearing the same tank top now."

Translated by the author. Originally featured in the Fall 1996 edition of "The Literary Review," published by the Farlaigh Dickinson University.

About the author

Azadeh Naderi is the pen name of an Iranian woman writer/translator who lives in California and is completing her Ph.D. in a literray field from one of the University of California campuses. (Back to top)

Related links

* THE IRANIAN Arts &

Literature section

* Cover stories

* Who's

who

Copyright © 1997 Abadan Publishing Co. All Rights Reserved. May not be duplicated or distributed in any form.

|

|

|