In search of morning

by sima

20-Nov-2007

Last spring I read Dar Josteju-ye Sobh (“In Search of Morning [1]”), the memoir of Abdorrahim Ja’fari, founder of Amir Kabir publishing house in Iran. It is an unforgettable book.

Ja’fari was born in 1919, a year after the end of World War I. Though we have all heard the stories, it is not easy to imagine Iran during the first world war: British, Russian, and Ottoman troops at large; the last Qajar Shah roaming Europe while the country disintegrates at the hands of local warlords; famine, cholera, typhus; destitute European refugees; bread made of flour cut with sawdust; death and devastation at home and in the news. It was still war time when Ja’fari’s mother, daughter of a poor widow, was married off to a middle-aged shop-keeper who promised some protection. When at thirteen she gave birth to Ja’fari in Tehran, the father had already abandoned them and vanished in the provinces. Mother and grandmother raised the child on a pittance of an income from spinning thread for a small socks manufacturer. Ja’fari’s earliest memories are of interminable nights watching two weary women bent over the spinning wheel, working until the wick burning in a dish of oil died out. With the death of the grandmother the very young mother was left alone to fend for herself and her boy. The child must go to school at any cost. But when in fifth grade the bright but restless boy dropped out of school mother had to find work for him.

The incident that set Ja’fari off on his life’s work is a scene worthy of Gogol. During a torrential downpour one night, mother and son return home on a bus. The dirt street is awash in mud. A very young man getting off the bus stumbles onto the mud at their feet. Ja’fari’s mother rushes to his help and a conversation is struck up. The young man is a worker in a printing house. At the mention of printing house a spark goes off in the young mother’s head. That is the way to work and study at the same time.

This may be the moment of conception of Iran’s largest publishing house but the arduous labor lies ahead. Ja’fari starts as an errand boy in a print shop and slowly learns the trade. The work is back-breaking. Workers show up first thing Saturday morning and live in the printing house until the following Friday morning, often never seeing the light of day for days. They sleep in increments of two hours. Working with lead, many fall sick with tuberculosis. But the young worker, often dizzy with sleep, reads the pages that the machines spit out. He reads books sheet by cut and folded sheet, and page by typeset page. In his rare free time he rents books from other publishers. His education continues as his mother has wished. Eventually he leaves to manage the bookstore of a trade publisher, where he meets some leading scholars and writers. He feels the great potential of new fields of learning, new books. When he finally sets up his own publishing house with the small capital he has saved from his wages, he has no interest in the common money-making genres: religious tracts, prayer manuals, pictures of saints, calendars showing auspicious and inauspicious days for doing things, and the occasional volume of treatise or classical poetry. The trade publishers that he knows try to dissuade him. When he persists, they expect his failure any day.

But Ja’fari’s choice of the name “Amir Kabir” for his publishing house showed that he has ideas beyond earning a living at a trade he had learned. Amir Kabir was the self-made prime minister of Nasereddin Shah Qajar who was almost single-handedly responsible for building a centralized and modern Iranian state. He was particularly revered for creating modern and secular institutions of higher education. In 1852 Amir Kabir was sent to his death by the Shah and the intrigues of his court. At the bathhouse at Finn Garden in Kashan today, the wax figures of Amir Kabir and the executioner who slashed his veins depict one of the most tragic moments in modern Iranian history.

Driven by equal measures of intellectual curiosity and enterprising spirit Ja’fari built his own version of the great Amir Kabir’s legacy. He educated the public as he educated himself. He saw the potential of the market for new works and ideas and devoted his considerable energy to building and expanding it. He helped create a reading public. By giving decent contracts and royalty to his authors and translators, the former print house worker ended up supporting a class of professional intellectuals. As businessmen go he was a rare breed; he took financial risks on the market for intellectual pursuit. And, lo and behold, Amir Kabir grew and prospered.

Ja’fari’s memoir is a monumental work—and not just because it is the memoir of an extraordinary man. It is the history of an era told through the publishing of the books that helped define it. Amir Kabir’s 1979 catalogue lists close to 2000 titles—classic and contemporary Iranian as well as translations—in fiction, science, history, poetry, social science, philosophy, art. The titles include encyclopedias and dictionaries whose commissioning was itself of historical significance. The translations were of works not just from the west but India, China, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. The children’s series, “Tales of Nations,” included collections of stories from around the globe, from Vietnam and Cambodia to Sweden and ancient Greece to American Indians. The choice of Amir Kabir’s two most opulent volumes was symbolic: the Shahnameh and the Koran.

Ja’fari was tireless and insatiable. He turned down no good title. He labored over every aspect of production. He sought out, negotiated with and cajoled the best, and sometimes most difficult authors, translators, artists, and printers. His wife sat behind the register at the store and helped him proof galleys at night; his children edited and translated. He was active with the Publishers and Booksellers’ Guild. He helped streamline the production and distribution of school textbooks. His business conduct and books were impeccable. He was a self-made man with no ties to the previous regime, a true son of the working class, and a heart-felt, practicing Muslim.

A few years after the revolution, after a great deal of persecution prior to imprisonment, he finally emerged from jail with his company and assets in government possession.

But Ja’fari’s memoir ends before the darkest years of his persecution. The final paragraph describes his return home after his first detention at Evin and the premature celebration of his family. It ends with: “None of us knew of the storm that was gathering and the catastrophes that were to rain on us…” Then follows an editorial comment: “The second part of this memoir will be published soon.”

The fate of the second part of the memoir was very much on my mind when I went to see Ja’fari in Tehran. I had looked forward to this meeting with great anticipation—it was, in a way, the highlight of my visit. Ja’fari’s memoir was a map of the intellectual development of my generation; I wanted to give him my respects. I was also curious to meet the formidable tycoon who acquired the publishing house at whose bookstore I had worked.

When in eleventh grade I decided to work in a bookstore during summer vacation, it was a novelty. Middle class high school students in Iran did not work summer jobs. I worked two consecutive summers before going to college in the U.S. My friendship with one of my oldest friends, Sohrab, dates from that time. On this recent trip I almost had to drag him to accompany me to visit our old store in the bustling book-row across the street from Tehran University. He kept shaking his head: “It really is not what it used to be. The best bookstores are not there any more.” His wife added, “He can’t go for so long without smoking.” Sohrab is a chain smoker and there is no smoking in Ramezan, so we picked a time close to eftar so he wouldn’t have to suffer for long.

“Out of print, college, foreign,” yelled hired boys on the crammed sidewalks of our old haunt. “Come on up, come on up…” Everyone was selling books: in storefront shops, up in the mezzanines of buildings, inside cavernous book malls, on basat spreads on the sidewalks. The store windows were a random clutter packed with obscure titles, obscure publishers, obscure authors and translators with “Dr.” titles. “How to” books, domestic and import mysticism, software manuals, modern poetry, religious tracts, reprints of old favorites (quite possibly without authors’ consent or contract), good books, bad books, printed matter that could hardly be called books… It was like a Google search come to life.

Our old bookstore, the flagship store of Jibi Books Corporation, was at the time the largest bookstore in the country. It was new and shiny and spacious. Every new book passed through many caressing hands before being placed on the shelves: the publisher, distributor, book seller, random employee, random customer… Hot discussions ensued on whether or where the new title should be displayed. It was lots of fun. Now we had a hard time finding the old store. We finally identified it by its familiar shelves; otherwise it was indistinguishable from other crammed and noisy stores. Where we used to have sitting chairs grouped together for impromptus chats were now racks and racks of books. The store was cut in half. The east wing of the store had been turned into storage where a few scruffy, distributor-types were unpacking boxes.

“You’re from the days before Ja’fari?” asked one of them, looking me up and down. “Boy, you’re old…!” I guess it showed on my face that I thought he was a scruffy, distributor type.

The fate of this bookstore is an interesting one. Jibi Books was owned by the Iranian office of Franklin Book Corporation. The Iranian “Franklin” (as it was called) was established in the 1960s by its American parent organization to promote books by American authors and give technical and financial assistance to Iranian publishers. But under its competent Iranian director it became increasingly independent from the American organization. Eventually, the Tehran Franklin became so successful and profitable that it lent support to its nonprofit parent in New York. But it accomplished a great deal more. It played a significant role in standardizing, printing, and distributing school textbooks. It collaborated with many publishers (including Ja’fari) in commissioning and producing new titles. Its imprint, Jibi Books, was an effort to make books more accessible by producing many titles in “jibi” (“pocket”) editions. This and other projects continuously expanded. The editorial board of the organization had an excellent reputation.

By the mid-1970s, however, the second director of Tehran Franklin pulled off a spectacular coup of corruption. He cashed in most of the corporation’s considerable assets and settled with the pocketed money in Los Angeles. When he auctioned off Jibi and its assets, including the bookstores, Ja’fari bought it. Two years later the revolution took place and what was left of Franklin was confiscated and renamed “Center for the Promotion of the Islamic Republic.” When the zealous new director of Franklin called Ja’fari to discuss the purchase of Jibi, the conversation took place across a desk with a bare gun placed on it. “You must return Jibi,” Ja’fari was told. They reached the agreement that Amir Kabir would be reimbursed and Jibi will be returned to the new Franklin. After a while Ja’fari was informed that the money was ready and that his employees were to hand over the bookstores on a certain date. On that day Ja’fari went to our old flagship store, waiting to conduct the transaction. Instead, he received a phone call that the reimbursement had after all not been approved. Jafari writes that during that phone call the name of a certain official in the Revolutionary Council was mentioned, the significance of which did not quite register with him. It did not occur to him that there were now ways through which not just Jibi but the entire Amir Kabir operation could be had for nothing. It was only natural that the reimbursement budget was not approved.

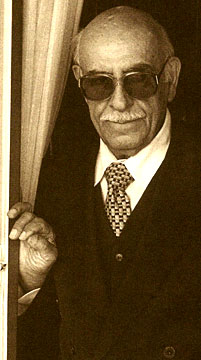

When I finally met Ja’fari, he was every bit as formidable at 88 as he had ever been. As we chatted in his living room his children one by one joined us. We talked about print-on-demand technology, electronic publishing, the internet, book returns, distribution, paper weight, etc. We did not have a lot of time and so much to say. We talked about translation of his memoir, the difference between Iranian and non-Iranian readership. But the second part of the memoir…? I was burning with curiosity.

A heavily edited version has been stalled in the Ministry of Guidance for some time now. There is no telling when we will be able to read Ja’fari’s account of his years after the revolution. This much, however, we can surmise: the history of this era will not be told through the books that he published. It will have to be told through accounts of persecution, violence, deceit, and betrayal. And the publication of the unedited version of the memoir—the un-self-censored version, that is—will have to be referred to our old friend, that unique realm of possibilities: Inshallah…

| Recently by sima | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

از طرف ثمینه باغچه بان: سیمین بهبهانی و روشنایی | 5 | Jul 15, 2011 |

| Guess what I've been up to | 9 | Apr 21, 2010 |

| Evlin Baghcheban | 7 | Feb 09, 2010 |