We continue to live with the memory of the Coup of August 19, 1953. There are still individuals alive who have vivid recollections of that tragic day.

Farhad Diba is the nephew of Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh. The son of Abolhassan Diba (Saghat-Dowleh ), he is one of Dr. Mossadegh’s closest living relatives. Farhad Diba’s grand-mother (Dr. Mossadegh’s mother), Princess Malektadj Firouz (Najmeh Saltaneh), was a grand-daughter of Abbas Mirza, the famous reformer and heir-to–be who died before ascending the Qajar throne. She played a significant role in Mossadegh’s upbringing.

A grand lady and a philanthropist, as well as a devout person, she married thrice, rare for her times, but dedicated her life to charity. In many ways, Mohammad Mossadegh saw his mother as the most influential person in his life.

He dedicated to his mother his doctoral thesis, “The Testament in Muslim Law,” written in French and submitted to the University of Neuchâtel (Switzerland) in 1914.

A nephew of Dr. Mossadegh, Diba is a member of the Qajar family. He witnessed the Coup as it was playing itself out on the streets of Tehran. A teenager then, Farhad Diba was there when his uncle’s house on Kakh Street was being ransacked.

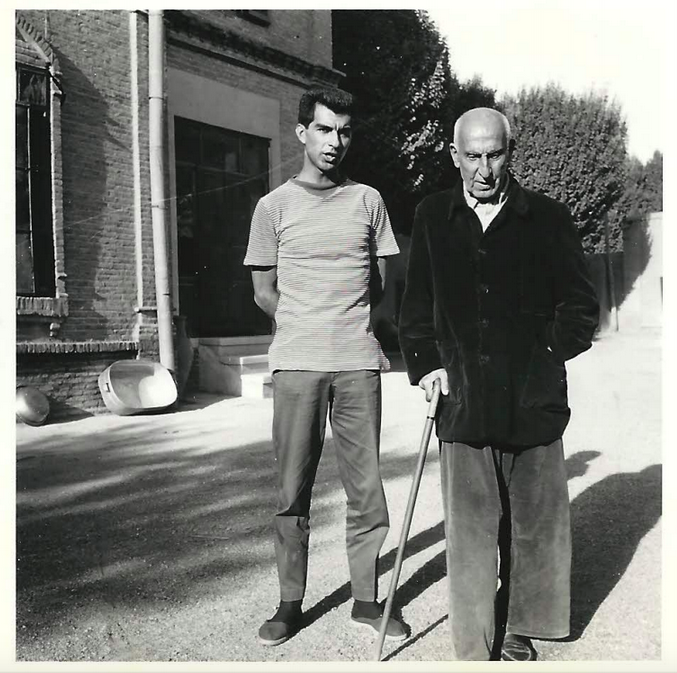

Farhad Diba is the author of the first English-language biography of Dr Mossadegh – Mohammad Mossadegh: A Political Biography (1986 ). In a recent interview, he recounted some of his very personal experiences as a youngster, in contact with his uncle. These constitute valuable firsthand insights, hitherto unknown, into the character of Mossadegh.

Here are some of his recollections:

“As I grew up, there were various phases of contact with my uncle.

The first phase was that, as a small child, my family would have lunch at my uncle’s house on many Fridays.

During those gatherings, we, young cousins, would play together and uncle was the figurehead of the family. Of course, before all else, we would go to greet him and he had a kind word for each and everyone of us. If it was our lucky day, we would get to sit with him for a short while.

One particular Friday, early in 1946, stands out vividly in my memory, most probably enhanced by an existing photograph, taken by Ahmad Mossadegh [one of Dr. Mossadegh’s sons who was also a talented photographer]. My mother stands with my sister and I, in a snowy courtyard on Avenue Kakh (uncle’s house), where we had gone to obtain his permission to leave for Europe, to boarding school. In the photo, I am smiling broadly, little knowing what idyll was being left behind or what fate had in store for that house, a little over seven years later.

The second phase was that of visiting Iran during school and university holidays. At times, uncle would be residing at Ahmad Abad and we would spend some nights there. There was an outbreak of malaria and, as a preventative, uncle would roll and cut some evil-tasting black pills, which we were obliged to swallow. I never found out about the contents.

This second phase coincided, for a while, with his premiership and also with 28 Mordad.

On a few occasions, during his time as Prime Minister, my father took me up to uncle’s bedroom, which also served as the office of the Prime Ministry. I was asked what I was learning at school and how I liked being in England. Upon leaving, uncle would invariably give me an envelope with a small amount of money in it.

At Norooz times, as I was at school and could not present my best wishes personally, I would write him a letter in my bad Persian hand-writing. Without fail, he would give my father a hand-written reply, containing a New Year’s present, to be sent on to me.

On 29th Mordad, the day after the Coup, soldiers ransacked our house, claiming that Dr. Mossadegh was being hidden by his brother. We were all put under house arrest, with a lorry load of soldiers posted at the gate until, a few days later, my father was able to arrange for my sister and I to return to school in England.

Later, when uncle was in prison, it was so sad for me to visit him in that situation. Although he never complained of being held in solitary confinement at a military prison, the air was heavily despondent.

My university breaks fell during his period of internal exile at Ahmad Abad. Again, on occasion, we would overnight there. He would stay in his room, with a few books around him, and come down to the dining room (which later served as his place of burial) for meals. The food was always simple but perfectly adequate, but he never seemed to be particularly interested in it.

Once he asked me what I was studying at university and when I replied “politics”, he was half-amused and half-shocked. He told me: “Haven’t you seen what politics has done to me?” As a man, as my uncle, he was a huge support. Being my father’s elder brother, he could give advice to my father. So, if I ever had a big argument with my father (and there were a few!), on the next occasion I would ask my uncle to intervene and, invariably, he sided with me.

On the many visits to Ahmad Abad, he never complained about his incarceration, at least not to us the younger set. However, an air of sadness was discernible and it was heart-rending, upon leaving for the city, to know that he would be all alone, in that desolate place, cut off from the world and, more especially, from the country and countrymen that he loved.

He never fully leant on the enormous popular support which he was given. He left the people to work out for themselves the right and the wrong of an action. A good example of this was the massive uprising in his favor, on 30th Tir.

However, on 26-28th Mordad, the people were duped by the conspirators to believe that Tudeh demonstrations were taking place, as had been the case some days before. Dr. Mossadegh must have known better and must have realized that another coup was taking place. Had he broadcast a speech on Teheran Radio, alerting the people to what was happening and calling on them to resist the putchists, history would have been very different. Of course, hindsight is a wonderful fix-all.

Finally, on a personal note, I have a memory of my uncle as strict but kind, generous with his time and caring towards his fellow human beings. He was a devoted husband and a strict adherent to the rule of law, and a humanitarian. Above all, he was a patriot.

I so wish that I had been a little older during his lifetime, so I could have had more meaningful exchanges about his life. A few extra years would have given me so much more insight into the workings of that great man’s astute legal and political mind.

“I miss him….”

The last time Farhad Diba saw his uncle was in Najmieh Hospital, on the day Dr. Mossadegh died. Dr. Mossadegh had requested to be buried alongside the martyrs of 30 Tir. But the Shah, in his desire for vengeance, denied him his last wish.

Farhad’s office was an octagonal Qajar building, previously a part of the home of his grandmother, in the compound of Najmieh Hospital. After its seizure, it was razed to the ground at the onset of the revolution.