Eighteen months after Washington quit the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, Tehran is proceeding with staggered steps away from its own compliance. The deal is unravelling against the backdrop of high regional tensions. A de-escalation along the lines developed by France provides an off-ramp.

Iran announced on 5 November that it is moving ahead with incremental breaches of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). According to President Hassan Rouhani, as of 6 November, Tehran will start “injecting [uranium hexafluoride] gas into the centrifuges in Fordow”, a bunkered enrichment facility that under the deal is meant to be converted “into a nuclear, physics and technology centre”.

This move is the latest in a series of staggered steps toward downgrading Tehran’s adherence to the nuclear agreement. The process began in May 2019, when the Rouhani administration set a 60-day rolling ultimatum for the agreement’s remaining parties (France, Germany, the UK, Russia and China) to deliver the deal’s expected economic dividends in the face of unilateral U.S. sanctions. It followed through on 7 July with a breach of the JCPOA’s quantitative cap of 300kg on low-enriched uranium and pushed past the quantitative limit of 3.67 per cent enrichment levels. Then, on 6 September, Iran started lifting limitations on nuclear research and development, including the activation of advanced centrifuges. These individual steps have been carefully calibrated to add urgency to diplomatic efforts without sparking an immediate non-proliferation emergency, with Tehran stressing at each stage that its measures are rescindable if the JCPOA’s core bargain – nuclear limits for economic normalisation – is fulfilled. “We are aware of their concerns vis-à-vis Fordow”, Rouhani acknowledged, “but whenever they fulfil their obligations, this step can be reversed”.

These individual steps have been carefully calibrated to add urgency to diplomatic efforts without sparking an immediate non-proliferation emergency.

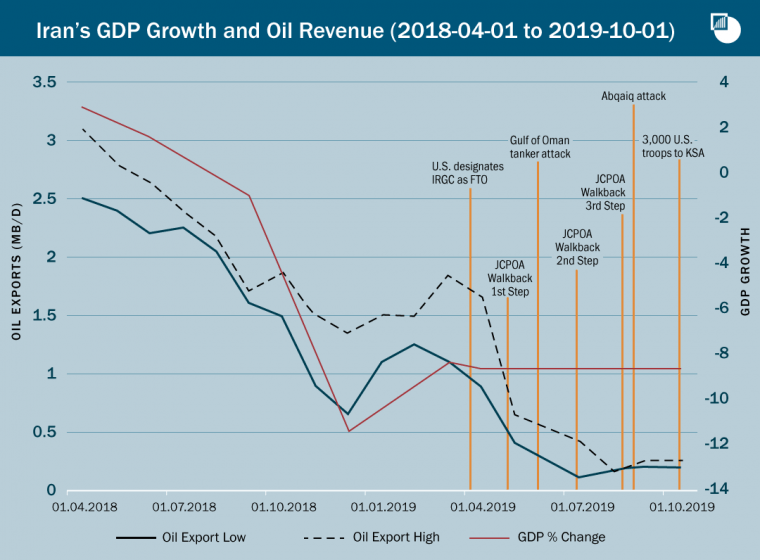

On the eve of the U.S. oil sanctions snapback in November 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was asked if Iran might restart its nuclear program. He responded, “we’re confident that the Iranians will not make that decision”. At the time, Tehran had opted for strategic patience in the hope that its nuclear compliance would encourage the rest of the world to continue trading with Iran in defiance of U.S. sanctions. When that assumption proved wrong, and especially after the U.S. in April 2019 revoked the sanction waivers that had previously allowed eight countries to import Iranian oil, the Iranian leadership started pushing back.

A senior Iranian official told Crisis Group that “we are in a full-fledged economic war. Even during the oil-for-food program, Iraq, which had invaded another country [Kuwait], was allowed to export its oil. The U.S. can’t strangle us and expect us to do nothing”. As the government in Tehran sees it, responding on the nuclear front serves three objectives: pushing the JCPOA participants, particularly the Europeans, to step up what have thus far been faltering efforts toward relieving the burden of U.S. sanctions; signalling to Washington that the cost of its sanctions will continue to rise unless it provides Tehran with some economic relief; and satisfying public opinion at home. As such, the Trump administration, which was concerned about the sunsets on Iran’s nuclear restrictions, has in practice moved forward the deadline for testing advanced centrifuges from 2026 and resumption of enrichment activities at Fordow from 2031 to 2019.

The other side of the coin of Iran’s nuclear brinksmanship is a volatile regional environment. A series of incidents also transpiring since early May, particularly around the Gulf, dramatically raised tensions in the months that followed: on 12 May, four oil tankers outside the Emirati port of Fujairah were damaged by limpet mines; on 14 May, Huthi drones hit two pipeline segments along the major Saudi east-west oil pipeline; a rocket landed near the U.S. embassy in Iraq on 19 May; a suicide attack in Kabul on 31 May, claimed by the Taliban but blamed by the U.S. on Iran, wounded four U.S. servicemen; on 13 June, two tankers were attacked and damaged in the Gulf of Oman; on 20 June, Iran downed a U.S. drone; on 18 July, the U.S. claimed to down an Iranian drone; on 17 August, up to ten Huthi drones caused limited damage to a gas plant at Aramco’s Shaybah facility; and on 14 September, Aramco’s Abqaiq-Khurais facilities were significantly damaged in cruise missile and drone strikes from as-yet undisclosed points of origin but in what the U.S., Saudi Arabia and the E3 contend was an Iranian operation.

Iran’s responses on the nuclear and regional fronts call into question the core premises of the U.S. “maximum pressure” campaign. While the Trump administration’s approach has, without doubt, managed to inflict significant harm on Iran’s economy, Tehran has broken the binary outcome of concession or collapse by instead adopting what it touts as “maximum resistance”. As a result, judged by whether those Iranian activities that the U.S. views with concern have decreased in the face of significant financial duress, there can be little doubt that the strategy has fallen short, delivering impact without effect and rather than blunting Iran’s capabilities only sharpening its willingness to step up its provocations.

The leadership in Tehran seems convinced that nuclear non-compliance and regional escalation have been more fruitful for them than compliance and restraint during the first year of the Trump administration’s maximum pressure policy. They can point to the uptick in efforts to mediate between Iran and the U.S., notably those led by French President Emmanuel Macron; the decision by some regional rivals, like the UAE, to de-escalate bilaterally; and the absence of direct military retaliation by the U.S. and its allies. Domestic politics, too, could increasingly play a role as Iran prepares for parliamentary elections in February 2020 and a presidential election in 2021: hardliners may welcome increasing tensions with the West as a means of further discrediting the Rouhani camp, which advocated for engagement with the West, while Rouhani’s administration could resort to more brazen escalations in a bid to secure relief from sanctions as a means of boosting its political standing prior to these crucial polls.

But for Iran to push ahead on either the regional or nuclear fronts, or both, is likely to prove a dangerous gamble. A significant incident involving U.S. forces or U.S. allies could result in retaliation by Washington, which has twice already (after the drone downing and Abqaiq attack) come close to the brink of a military clash with Iran. Iran and Israel are also on a knife-edge, with Israel far less reluctant to take military action. The breaches of the JCPOA could also threaten the deal’s core non-proliferation objectives to such an extent that the Europeans find themselves with little choice but to trigger the deal’s dispute resolution mechanism. That process could result, within the 65-day timeframe defined in the deal, in the snapback of all the UN sanctions on Iran, which could in turn push Iran to withdraw not just from the JCPOA, but also from the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). With mutual consent, however, the adjudication process could be extended indefinitely.

But for Iran to push ahead on either the regional or nuclear fronts, or both, is likely to prove a dangerous gamble.

A ceasefire deal that would freeze tensions and allow both sides to take a step back from the brink remains the best way out of a dangerous spiral downward. This would require Iran’s leadership to accept the reality that despite President Donald Trump’s interest in a wider agreement Washington is unlikely to revert to its pre-JCPOA withdrawal sanctions posture, and the U.S. to acknowledge that Tehran is unlikely to agree to the kind of high-level summit Trump is seeking with his Iranian counterpart without an assured return. Marrow-deep mistrust is hard to overcome, even when mediators are involved. Referring to Macron’s efforts to arrange a meeting between his Iranian and U.S. counterparts on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly meeting in September, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei noted, “The French president, who says a meeting will end all the problems between Tehran and America, is either naive or complicit with America”.

A narrower version of France’s initiative, by which Iran would return to full JCPOA compliance and refrain from direct or indirect regional provocations in return for the E3 providing (and, importantly, the U.S. facilitating) a financial reprieve in the form of an increase in Iran’s oil exports offers the best available off-ramp. President Rouhani has talked about reverting to the 1 January 2017 status quo. A more realistic milestone is 1 January 2019, when Iran was able to export about a million barrels of its oil while it was still in full compliance with the JCPOA. At the same time, rumours are circulating about a prisoner swap between the U.S. and Iran. Such an exchange would be an important gesture and a means of opening a sorely needed communication channel.