Page

2 Page

2

>>> Page

1

The formal space of Abadan, as I mentioned before,

consisted of several segregated neighborhoods, the residents of

which were carefully assigned housing according

to their job, rank in the company roster, and even race, nationality, and ethnicity.

A rigid and inflexible hierarchy defined the neighborhood, street, alley, and

specific house of each individual employee according to his rank, work record,

skill, and even ethnicity, and assigned a house to his family (the employees

being all male).

Senior European staff was housed in 'Braim',

[see: Summer

of 1978] which consisted of large villas

and bungalows set on green lawns, surrounded by parks

and gardens and lined with English hedges, and built on lots averaging 1000

sqm, and 4.5 units per hectare. Workers' neighborhoods, such

as Bahmanshir, Bahar, etc., were row houses with high walls and

tiny courtyards, built in

straight lines and wall to wall, averaging 120 sqm, with a density of 26

to 31 units per hectare. In between these extremes poles laid the middle

and

lower staff neighborhoods, such as Bawardeh, which were combinations of these

two

forms in terms of architecture, design, and scale. [see: Bird's

eye]

The spatial discipline that laid out Abadan's urban design like a chessboard

was not as spectacularly successful in subjugating the rugged hills and mountains

of Masjed Soleyman to its rational blueprints. Consequently, the design of

Masjed Soleyman appears to be fragmented and unplanned. Nevertheless, as formal

company neighborhoods were laid out in the vicinity of workshops, oil wells,

and industrial installations closer scrutiny will show the same segregationist

and segmentationist approach as in Abadan, but on a more spread out and disconnected

pattern.

With the passage of time and successive political

developments, such as the ongoing haggling between the government

of Iran and the company over

the composition of the labor force and the distribution of profits from

the operations, the share of Iranian employees began to rise considerably.

Gradually,

the racial segregation that separated the spaces of routine interaction

and daily life between Iranians and the English became less marked,

in comparison

to the occupational and class distinctions that served as the norms of

segmenting city spaces.

Despite all this, what truly set Masjed

Soleyman and Abadan apart

was the cities' glaring modernity, reflected in their unique architecture

and design, but also in most other details of urban space and life. These

cities were the sites of the first airports, motor vehicles, cinemas,

technical schools,

mixed schools (boys and girls, foreign and Iranian) [See: Back

then],

leisure clubs, sports clubs, bus services, mass transports, luxury

inns,

well

equipped hospitals,

etc. in Iran and the region. At the same time, all these amenities were

segregated for different social layers and classes, to the extent

that Masjed Soleyman

even had separate cemeteries for workers and staff [44].

This system allowed the social position and status

of each individual employed by the company to be public knowledge

through his residential

address,

the means of transportation and the medical facilities he and his family

were

allowed to use, the country and sports clubs he was allowed to join,

and the schools

his children could attend. At the same time, because the company's

internal organization was also to a large extend a meritocracy,

and as each step

up the career ladder translated into greater material privileges and

social status,

the workers were encouraged both to feel envious and to compete against

each other, and to pursue individual and personal rather than collective

benefits

[45]. Transforming urban amenities and city spaces into symbolic capital

is one of the most effective instruments of controlling the population

in these

cities [46].

Modernizing the household

The authoritarian spatial design of company towns both reflected

the social relations that prevailed within this industry, as

well as reinforcing

and

reproducing them. The Company had to not only house its workers (initially

there were no

housing available in these barren locales), but it also had to adapt

this raw labor force to the rigorous and special demands of modern

industry. It had

to retain them, to keep them relatively satisfied or at least dependent

on wage labor, but also and at the same time docile.

We can witness

the reflection

of all these goals in details of the urban design, from the architecture

of the houses to the types of materials used in their construction,

in the different

designed and organized spaces of entertainment and leisure, the types

of

walls surrounding the residences and their heights, the length and

width of streets

and alleys, the morphology of planned formal neighborhoods, the types

of kitchens and bathrooms implemented in individual units, etc.

The French geographer Xavier de Planhol has argued

that the walled-in row houses of the workers were designed to duplicate

native architecture

and

a sense of

privacy, rooted in 'Islamic values' [47]. There is a striking similarity

between this argument and rationalization of the demolition of

old neighborhoods of Algiers under French colonial rule, at about

the

same time, in the

inter war period [48]. These neighborhoods were replaced with modern

apartment blocks,

designed by French architects and urban planners, who also tried

to incorporate 'native' and 'Islamic' values and norms in their

constructions.

In fact,

far from reflecting the domestic

architecture of the rural and tribal origins of the migrant laborers,

these row houses were designed with two apparent purposes in mind:

first, the mass

production of a great number of cheap and durable houses and second,

to directly intervene in the domestic space of the family and to

modernize

it [49]. The

tiny courtyards and high walls prevented air circulation, especially

in the atrociously humid and hot summer months.

The widespread

use of new or modern

construction materials, such as bricks, stones, and metal frames,

instead of adobe and wood, were faster, standardized, and cheaper

but unlike

traditional

materials, did not have the ability to modify extreme seasonal

and climatic fluctuations. As a result, these new houses depended

on

modern amenities,

such as electricity, fans, some form of air conditioning, and heaters

(gas and electricity,

provided by the Company, overtime became common features in Company

housing). The provision of these modern amenities, as well as sewerage,

piped water,

and medical facilities helped to augur in new notions of personal

hygiene and public health.

The monopoly ownership by the Company of the means

of production, as well as reproduction is the main instrument of

social control

in company

towns.

In

other words, both occupation and the source of income are in the

monopoly of the company, as well as real estate, housing, and social

services.

The household

unit, aside from being the smallest, collective social unit, plays

a key role in many societies in shaping the 'individual', and in

placing him/her within larger networks of social relations. For

this reason macro social institutions

and powers, such as capital and the state, consistently attempt

to penetrate the household, and to shape and regulate it according

to their norms and interests.

This intervention often requires the imposition of radical change

upon existing household organizations, and sometimes even the prevention

of the survival

of these older forms.

The rigidly fixed residential architecture

of Abadan and Masjed Soleyman, enforced by the Company who owned

the real estate and

housing stock, prevented the accommodation of large extended families,

the basic unit of social life in the region. Nor did it allow the

use of the domestic

space for economic and productive activities, through the maintenance

of livestock and chicken, the production of meat, dairy, and eggs,

and vegetable garden

plots. The small, one or two roomed houses were not even practical

for traditional handcrafts, such as kilim weaving.

All these activities,

quite widespread in

the region up to this day, are crucial for making the household

into an economic unit, despite their small scale, by providing

income and food supplements.

They also bestow status and a sense of identity upon the household,

and provide it with relative economic autonomy and self-reliance.

As importantly, these

activities also happen to be the realm of the economic agency of

children and especially women.

Overall, this domestic architecture

promoted the nuclear family as its privileged unit, but it also

altered gender roles within

the

household, as well as the

other major division of labor between different generations. In

this setting the adult male becomes the sole legitimate economic

agent,

in

the sense

of his productive activity being socially validated, through the

labor market.

The workplace is thus separated and set apart from the place of

residence, and the result of his economic activity would return

to the household

in the form of a money wage or salary.

The other consequence of

this spatial

division

of labor is that the house becomes the exclusive domain of the

wife/woman, but deprived of the economic and productive activities

it previously

allowed. At the same time, domestic space also becomes a boundary,

between the private

and the public domains, and thus a physical constraint for women

who no longer can easily and routinely cross the porous boundaries

of the

household

space.

This spatial and gender division of labor, the new

role assigned and imposed upon women which in many ways dramatically

limited

their social

roles and,

in short, this 'modernization' of the household which so characterized

life in Abadan and Masjed Soleyman reflected directly the developments

that were taking place in the capitalist West at about the same

time. Contrary to

the extended household, the 'modern' nuclear family, a form imposed

by the domestic architecture of company towns, curtailed the number

of children and other generations or relatives who could live under

the

same roof, primarily

because of the shortage of space and the design of the house.

Ordinarily,

the only other generation who could reside in these houses were

the children who,

instead of participating in collective household productive activities,

were sent out of the home to schools (vocational and regular) in

order to replace

their parents eventually at home, workshop, refinery, and oil field

after several years of disciplined training and socialization [50].

This modernization of the family, gender, and women

has been a mainstay of 'modernity'.

However, its early imposition from above in Khuzestan's company

towns set the stage for its replication in later periods elsewhere

in the

country, long after AIOC had relegated its role to the oil Consortium

and the

Iranian State.

The anomie and social problems mentioned have remained

acute in newer

and smaller company towns of Khuzestan and elsewhere, such as

the agro-industrial model villages of Dezful, the sugar cane plantations

of Haft-Tappeh,

the steel town of Mobarakeh, the copper mining town of Sarcheshmeh,

the industrial machinery

town of Arak, etc. This is especially the case for women, where

geographic isolation and their seclusion in the household is not

relieved by

the large scale of the urban setting and the diversity of city

life, as

it was in Abadan

and Masjed Soleyman [51].

Possibly discontent in smaller company

towns is caused by the smaller scale and the cultural poverty of

these towns,

whereas what

distinguished Abadan and Masjed Soleyman, as we shall discuss later,

was their exponential growth, in spite and against the wishes of

the Company, and their

maturation into large and multifaceted cities which did come to

produce diverse, autonomous, and cosmopolitan spaces and a vibrant

urban

culture and life.

Public Space

The wide boulevards and the grid pattern that characterized the

formal space of Abadan distinguished it from other Iranian cities

at the

time. Khuzestan's

historical cities, Dezful and Shushtar [52], follow the local physical

topography, primarily as the means of water allocation by gravity.

They have narrow, winding

alleys and cul de sacs, lined by high brick or adobe walls, intended

to defend neighborhoods from wind and dust, extreme fluctuations

in climate, and from

physical and military attacks and molestation. In these cities

an important part of social life and relations flows and is shaped

in

the public

space of streets and bazaars.

The formal public space of company towns differs

from this historical model in several important respects: In Abadan,

instead of long

and narrow winding

alleys forming a maze, the front doors of the row houses open onto

either short, narrow, and straight alleys which abut onto large

streets at both

ends, or

directly onto large avenues. In this way each house is set up as

distinct from its neighbors, and separated from the neighborhood,

the intimate

street life,

and ultimately from the workers' society. Any collective protest,

or suspicious gatherings among neighborhood residents can be quickly

detected,

and each street, alley, and even neighborhood can be easily cordoned

off from the others should the need arise.

The assignment of housing by the Company, based

on occupation and rank (and race, in the early days of British

ownership), and the

constant

displacement of the personnel within the company hierarchy, made

the forging and maintenance

of lasting spatial solidarities difficult. Because the independent

ability to chose one's residence is denied the workers seeking

company housing,

the formation of autonomous and spontaneous networks of solidarity

in space by using common kinship, ethnic background, or geographic

origins,

are near

impossible to form.

In Abadan, the obsession to use urban space as an

instrument of controlling the population can be readily detected

in the details

of the design

neighborhood and public spaces of the formal city. Forty years

ago, the French sociologist

Paul Vieille and his collaborators pointed out some of glaring

examples of these coercive aspects of the urban design of Abadan

in a study

that is still

one of the best published examples of spatial analysis in Iran

[53].

The motives followed in the urban design of Abadan,

they argued,

were not the

conventions

of urban planning, nor the price of land and economic calculation,

but the separation and distinction of different areas of the city

from one

another

by a central authority. It is self evident that if different city

neighborhoods were constructed adjacent to each other the provision

of common services

and infrastructure would have been far cheaper due to the economies

of scale.

In

fact, city neighborhoods were built apart and separated by wide

stretches of empty terrain, wide roads, pipelines, administrative

and industrial

facilities and, of course, the enormous bulk of the refinery itself.

This imposed separation

prevents easy intermingling and routine pedestrian interaction,

as well as potentially dangerous collective congregation between

separate

city

sections.

Roads do not connect different city sections to

traffic exchanges. Rather they end in several bottlenecks that

allow the surveillance

of all communication

between different parts of the city. The boundaries of different

neighborhoods are marked by guard posts, and there are regular

police stations near

or at

the entrance of workers' neighborhoods.

The Abadan Refinery was

the monopoly owner of all land in the formal company town. It

was responsible

for

organizing different sections of the city, as well as creating

and maintaining the distinctions

between its different parts. It was the force responsible for

creating the segregated and hierarchic landscape of the city.

In Masjed Soleyman, the topography and physical

setting had to a large extent aided and modified the process of

social engineering.

Houses

and urban facilities

were constructed, in a spread out fashion, around oil wells and

industrial

facilities. Specific neighborhoods were often called after these

facilities -for example 'Nomre-e Yek' (Number One, referring to

the first

discovered oil well), 'Nomre-e Chehel' (Number 40), Naftak (Little

Oil), Naftoun, etc.

The distance and area between neighborhoods

was connected by narrow, company built roads, and rugged hills,

left

barren and undeveloped.

Every action for building unauthorized hovels and houses was immediately

confronted by the Company's bulldozers. Like Abadan, official Company

areas were

built separately from one another, and had only one narrow access

road in and out. Neighborhoods are designed either in circular

pattern, or as parallel

streets which are interconnected by perpendicular streets, but

dead end on both sides cutting and isolating the neighborhood with

the

world

beyond,

except

thorough the single, easily guarded access road.

Company neighborhoods are segregated according to

rank and status, set in separate places with different amenities

and characteristics.

The

senior managers live

in 'Shah Neshin' (Seat of the King), senior staff in Naftak and

Talkhab, junior and petty staff in Nomre-e Chehel, Camp Scotch,

and Pansion-e Khayyam, and workers in Naftoun, Do Lane (Two Lanes)

Seh

Lane (Three

Lanes), Bibian, etc.

The space of leisure and entertainment in Masjed

Soleyman, as in Abadan, was differentiated according to rank and

class. Senior

staff and managers

had membership

to 'Bashgah-e Markazi' (the Central Club), junior staff had the

'Bashgah-e Iran', and workers Bashgah-e Kargari (Workers' Club),

located in

Naftoun. Only members and their guests had access to each club.

The rest of the city's population, not employed by the Oil Company

had no right to

use company facilities, especially the clubs.

All these social

clubs had more or less similar facilities, such as cinema, restaurant,

cafeteria, swimming

pool, ping pong, bingo, billiard, etc. The difference was not so

much in the range of amenities as the quality and, more important,

the prestige conferred

by membership in each institution, which played an important role

in bestowing symbolic status on individuals and their family. In

Masjed Soleyman even the

company stores and types of 'ration' assigned to each member was

distinguished by rank and social class [54].

Production of place

as a contested process

Place is a social construct which both constitutes and is constituted

by social relations. The production of place and the interpretation

of its

meanings are

equally contested processes. People and institutions struggle over

defining, using, and shaping space and place according to their

individual and

collective interests. We have been discussing how APOC built Khuzestan's

oil towns and the architectural and design rational behind it.

I have argued that this

rational was both utilitarian, as well as a discursive exercise

of power.

The Company wanted to attract and maintain a labor

force that

would be

at the same

time competent, efficient, modern, and submissive. However, there

has always been a fragile balance between the power of the Company

over

place, and its

own clear lack of autonomy from both global markets, as well as

domestic and local dynamics. On closer scrutiny we can see that

the structured

coherence

of this industrial landscape has always been shaky and open to

contestation.

Company towns of the 20th century, as mentioned

before, have been designed by using two contradictory as well as

complimentary principles:

The

idea of general welfare and the assimilation of the labor force

into the generic

values

of the 'middle class' and, on the other hand, the praxis of colonialism,

both internal and external, in the form of a one sided domination

over an alien and weaker region and people, for the main purpose

of the

extraction of their

natural and human resources and abilities. Contrary to the first

principle above, the aim of colonial social planning is not necessarily

to integrate

and standardize the subjugated region and people into a larger

unit (national, for example), but rather to create and proliferate

its

internal divisions,

differences, and distinctions in order to better control and dominate

it.

The presence of both these principles can be detected

in Abadan and Masjed Soleyman: These cities were built in isolated

regions,

away

from any

significant centers of population. Their designed physical and

cultural space precipitated

a break between the new and migrant population and their mostly

tribal and rural background and surroundings. Various planned aspects

of

the city design

and organization generated and maintained new norms, principles,

and behaviors conforming to the needs of modern industry. In other

words,

even though

the Oil Company was not a 'colonial power' per say, nevertheless

it both made free use of colonial practices and mechanisms, as

well as

relying on principles of corporate welfare policies.

The standard

of living,

services, level of education and technical training, and the overall

urban culture of

Masjed Soleyman and Abadan exceeded the rest of the country for

a long period. In Khuzestan the Oil Company created a wholly new

and

modern

society. However,

the lasting legacy of this experiment was not embodied only in

the physical structures it put together. Long after the political

events

of the oil

nationalization movement and the 1953 coup détat brought

about the end of AIOC and its total hegemony over the oil fields

of Khuzestan, the social imaginary and the

collective forces and institutional practices it had produced have

continued to exert a significant influence. The cultural, geographic,

and institutional

legacy of AIOC influenced not only the industrial proletariat and

management but also had a deep and lasting impact on Iran's then

and future 'social

engineers', namely the planners, urban designers, professional

elites of various kinds, industrial managers, and technocrats.

Abadan soon witnessed the growth of a spontaneous

city, with a 'native' architecture, bazaars, 'informal' residential

and commercial

neighborhoods,

illegal

hovels and shanties, and especially forbidden places housing brothels,

drug sellers, and smugglers who made the most of the location of

the city on the

international border. These subversive places grew across from

the manicured lawns and hedges of fancy Company neighborhoods such

as

Braim and Bawardeh.

Workers' squatter neighborhoods like Abolhassan, Ahmadabad, and

Karun, were rapidly constructed next to formal Company compounds

with fancier

literary names such as Pirouz, Bahar, and Farahabad.

The formal

Company town's 'public' space

was confined to clubs, sports fields, stores, and amenities that

only employees of the Company had access to. In contradistinction,

the informal

Abadan city

with its anarchic streets and constant and never stopping urban

confusion and hubbub, its colorful stores, streets teeming with

pedestrians

and people until

the wee hours of the dawn, presented a lively, adventurous, exciting,

untamed and unsupervised public arena to all citizens, whether

employed by the Company

or not. The two cities confronted each other with striking

contrasts: the formal city was affluent, comfortable, ordered,

and staid.

It was shaped by disciplinary

powers of separation, distinction, ranking, and surveillance

that kept its residents under constant control. The spontaneous

and

informal city was a public

place, in the more accurate sense of the word. It was open, integrated,

public and, at the same time, quite hectic and anarchic [55].

In these 'free zones' which did not belong to the

refinery and laid outside its control and surveillance all manners

of people

inevitably worked, cohabited, and mixed together: villagers and

tribesmen, Arab,

Lur, Bakhtiari, Turk, Esfahani, men and women, rich and poor, etc.

A third of the

population of the 'Bazaar' neighborhood and some 60% of residents

of the notorious Ahmadabad were Company employees, who were forced

to settle in these neighborhoods due to a chronic shortage of company

housing.

In other

words, the Company's efforts to mold and create an ideal society,

fit to satisfy its needs was consistently subverted and ran into

crisis

as a result of the formation of these adjoining, visible, and

accessible free zones. As

a result of these tensions and the co-presence of alternative

places the tight and controlled cast of the planned company town

was continuously

broken, making

Abadan and Masjed Soleyman lively, cosmopolitan places with a

strong sense of identity and a sophisticated culture [56].

The point is

that no matter how

powerful the Oil Company and its economic resources and organizational

means, it could not in the end manage to impose a full hegemony

upon the place it

had created. Spontaneous civil institutions, informal networks

of trade, guild, political, religious, and ethnic activities

were always

prominent

and exceptionally

active in Abadan until the Iran Iraq war destroyed the city.

In Masjed Soleyman also an extended and bizarre

informal and illicit space grew around the formal Company area.

The grand buildings

and geometrically aligned company structures contrast with squatter

settlements

that after

nearly a century have become permanent fixtures of the city. As

mentioned before,

Masjed Soleyman's topography is odd, as the city is constructed

in a rugged mountainous region, around a series of seven hills.

To quote

Kamal

At'hari's excellent study of Masjed Soleyman, "As the Company

prevented the construction of housing units adjacent to its own

residential

areas migrants were forced

to build their dwellings where the company bulldozers were unable

to reach and destroy. As a result of this the social, class,

and economic differences

of the city are reflected in and defended by the sheer cliffs,

and deep gorges and flood channels. The city is divided into

neighborhoods with English names

such as 'Camp Scotch', 'Khayyam Pension', and 'Western

Hostel', as opposed to [rugged and informal areas with local

names such as] 'Kalgeh', 'Sar Koureh' ('By the Smokestack'),

and 'Mal Karim', 'Mal' being the smallest social unit

of the Bakhtiari [57]. Conclusion

In a classic study of the impact of French colonial rule on Algeria

Pierre Bourdieu and Abdelmalek Sayad use the terms 'acculturation'

and 'deculturation'

to describe the different experiences of displacement among the

mountain Berbers

versus the forced resettlement of Arab population on the plains

of Algeria.

The argument goes that the Berbers, among other

reasons, due to the more

rugged and inaccessible geography of their settlements, maintained

a greater degree

of internal autonomy than the more geographically vulnerable

Arab population of the coasts and the plains. Although many

cultural

and

economic tenets

of French rule penetrated the Berber society, nevertheless Berber

communities managed to maintain a sense of internal coherence

and ethnic solidarity

which

allowed them to adapt and even use many of the material benefits

accruing from this European encroachment.

The Arabs, on the other

hand, were

more vulnerable

and, despite fierce resistance, were turned into an instrument

for successive experiments in social engineering, which included

the

massive destruction

of towns and villages, the forced resettlement of whole populations

in concentration

camps, military zones, and planned housing complexes and neighborhoods.

The experience of Arabs was a brutal, alienating, and profound

deculturation compared

to the acculturation of the Berbers whom, despite the hardships

they had to endure, at the same time managed to accumulate certain

abilities

and resist

other encroachments [58].

In Khuzestan, the establishment of company towns

and model villages in the agro-industries of Dezful in the

1970's, and the semi-forced

resettlement

of tens of thousands of peasants, which has been the subject of

a thorough study

by Grace Goodell [59], was a deculturating experience. But it would

be difficult

to pass the same kind of judgement on Abadan and Masjed Soleyman,

despite the fact that they were the first and by far the most massive

such

experiments in social engineering.

Despite the fact that life in

these cities led

to undeniable

and fundamental changes in the social life and the culture of their

population, nevertheless this migration was voluntary in the end,

while in the cities

themselves, thanks to the diverse and large population and the

dynamic urban setting, the

possibility of negotiation and enough room for individuals to maneuver

was available. Consequently, Abadan and Masjed Soleyman had, on

the one hand,

a modern and authoritarian structure and organization, while on

the other hand,

thanks to the heterogeneity and energy of their population, as

well as the forbidding scale the cities had reached despite the

company's

wishes

and attempts, this modernity always remained conditional. The result

of these contradictions were cities and urban cultures that were

energetic and dynamic,

but also eclectic and hybrid.

As mentioned before, Abadan and its citizens

played a significant role in the revolution of 1979 and its

victory. Its physical destruction

during the

Iran

Iraq war and the forced dispersal of its population not only eradicated

an important city but also severed a unique industrial and urban

culture,

a

mature and advanced urbanity, and a human capital that had been

accumulated over seven

decades, from the physical space where it had been engendered.

Today,

after a decade of 'reconstruction', Abadan is only a shadow

of its former self. Its population, which had reached 300 thousand

on the eve of the Revolution,

some six years after the War (1994), when the population country

had almost doubled compared to two decades before, was only

213 thousand. The war severely

damaged the refinery, urban infrastructure and facilities, neighborhoods,

and palm groves around the city were severely damaged.

The

process of post war

reconstruction has been running into serious criticism by the residents

[60]. The activities of the refinery and oil industry are still

limited and minimal.

Many of the workers and staff are not native to the region. Many

of the Abadanis who have returned because of their attachment

to their city are dissatisfied

and await retirement to settle elsewhere. The morphology and fabric

of the city has been altered and its population, like the early

years of its founding,

contains many rural and tribal people, while the industrial labor

market and the economic institutions no longer have the old

ability and resources to shape

and influence the population, or to employ them.

Social problems,

especially addiction and smuggling, primarily due to an economic

depression, are rampant. But the worst problem is that of the

young generation of Abadanis who, for a significant part of

their lives, have

lived and

grown up as refugees and

migrants elsewhere - in Tehran, Ahvaz, Esfahan, Shiraz, etc.- and

find contemporary Abadan both alien and alienating. The cultural

continuity and the accumulation

of place identity which gave such a unique character to this city,

was violently severed at one point, and little has been done

to revive or save it from oblivion.

Masjed Soleyman has not been spared a troubled

and uncertain faith either. After the decline of oil resources

there in the

late 1960's,

and the

final shutting of its remaining oil wells in 1980-81, the city

has been faced

with a chronic decline. The government transferred most of oil

facilities to the

army on the theory that replacing one gargantuan institution

with another will prevent the disintegration of the city, as

it had

happened in

small oil towns

like Naft-e Sefid and Haftgel. More than half of the 2600 Company

housing units were transferred to the army [61].

But, according

to all signs

this strategy

has been hardly successful, and Masjed Soleyman failed to become

a military company town. Instead, the city found a special

place in the

regional

life of the Bakhtiari tribes. In a twist of historical irony,

the city that

not so long ago was one of the most industrial cities of Iran

and the Middle East, today limps along mostly thanks to the

presence

of nomadic

tribesmen.

The gradual

metamorphosis of the city, from a migrant, industrial and

class based space into an ethnic and tribal one can be easily

detected

in the

dominant dress

code on the streets, made of the distinctive Bakhtiari tribal

cloths, and in the proliferation of spontaneous housing

constructions in

hitherto forbidden

and inaccessible areas. The absence of capital, like blood

circulating in

veins,

can be easily noticed in the dilapidated conditions of

the city, and especially in the company neighborhoods. Many

of

the skilled

personnel

and workers

have migrated elsewhere and play an important role in the

strategically important

provincial industries, such as sugar cane, the Abadan refinery,

ports, steel mills, and oil facilities.

The intellectually

influential journal "Iran-e Farda", which in its initial

issues used to propagate an economy without

oil, and

considered the period of 1952-3 when Iran's oil was boycotted

by Britain during

the oil nationalization crisis and movement as a model

of independent and balanced national development dedicated

a

special recent

issue to Masjed Soleyman [62].

The basic theme of this issue was a grim and dire warning

about the inevitability of the end of oil production and

revenues

as resources run out, and the subsequent

social dislocations and pathologies that will result if

appropriate care is not taken to deal with this eventuality.

From this

important journal's

viewpoint, delinquency, unemployment, addiction, and depression

are the main characteristics of an abandoned and oil-less

Masjed Soleyman, and by extension

the future of Iran itself. Even in their decline Khuzestan's

oil towns continue to capture the collective national and

intellectual imaginary in significant

ways.

But perhaps the most important change in Masjed

Soleyman has taken place in the local structure of land ownership.

In 1956

more than

half of city

residents

were renters and less than a tenth of the city's housing

stock was privately owned. Currently, these ratios have

been almost

reversed and most of

city dwellings are owned privately. The turning point

on

this issue was the exhaustion of

the local oil resources, as well as the 1979 Revolution.

The collapse of the Monarchy led to important changes

in property

relations

and

land ownership

in all urban, and to a lesser extent rural areas [63].

The populist-socialist and the conservative-traditionalist

factions

of the Islamic regime

battled for years over their conflicting notions of

property rights, with the

former faction favoring widespread confiscation and

distribution of rural and urban

land among people, and the latter defending the sanctity

of ownership under Islam. True to form Ayatollah Khomeini

played

the middle

of the road on this

sensitive topic.

The end result was the confiscation

(often arbitrary) of the properties of the 'direct associates

of the former regime',

on the grounds of being illicit wealth, without affecting

general property relations

at all. These remained protected under Islamic law.

At this level, the redistribution of land became a political

process,

rather

than a universal legal one, and

therefore remained a limited, coercive, and often

arbitrary occurrence, subject to manipulation and abuse. On

the

other

hand, due to

the weakness of the new

regime, in place strict zoning laws, defining public

land, and permitted construction or cultivation areas

were overstepped

wholesale by a politicized population,

hungry for land.

By 1980 the metropolitan area of

Tehran and most other cities had expanded manifold, as hitherto

public

land

was

occupied and converted to

housing on a massive scale. In rural areas a similar

process happened to significant areas of state owned

and public

lands (nearly a

million hectares altogether)

which were occupied and de-facto expropriated.

This appropriation was based on the Islamic stipulation that

any

barren

land

'revived' and maintained

for at least three years by labor shall become

the possession (and not the 'property', that final status being

the

privilege of the

Divine) of the laborer/cultivator.

In Masjed Soleyman

most existing constructed areas were under the monopoly ownership

or possession

of the Oil

Company in

1979. IN

1979-80, when

this sudden takeover of the mostly unbuilt and

barren areas of the city happened

on a wide

scale the landscape of the city radically altered.

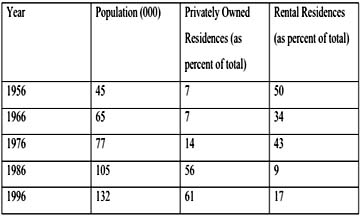

In Masjed Soleyman the shifts in ownership ratios

were far

more striking

than other

urban areas

(see table

1). The barren spaces and empty areas that under

Company dominion separated neighborhoods and

inhabited places

are today filled

with densely built

hovels and houses, and ad-hoc constructions which

have transformed the hitherto

fragmented and dispersed geography of the city.

Masjed Soleyman has become an interconnected,

very 'long' and spread out sprawl!

Table 1. Population and Housing in Masjed Soleyman

Sources: Ministry of Interior,

National Census of Population and Housing (Tehran, various

years); Kamal

Athari,

''Masjed Soleyman; sherkat-shahri madaniat-yafteh'',

Ettelaat-e

Siasi Eqtesadi,

No.47/48

(1991),

pp. 65-69; "Ministry of Housing and

Urbanism, Rahnamaye Jamiyat-e Shahrha-ye

Iran, 1335-70

(Tehran, 1989)

The city's population, which had a very rapid

rate of annual growth of 3.7% in the waning

years of

maximum oil production,

between

1956-66, witnessed a rapid decline to 1.8%

in the next decade (1966-76). But

the

following decade,

1976-86, the years of war and revolution,

of the end of oil production and related

jobs,

which were

years

of de-facto

economic depression

and accelerated

emigration from the city, the city population's

growth rate

reached 3.1%. One of the main causes of

this expansion was the immigration

from adjacent

rural and tribal areas. A major motive

for this movement of population was the opportunity

to

squat and permanently

occupy

urban land.

Struggle over possession of land and the

housing question have always been strong

motives in

shaping the geography

and identity

of company

towns.

But the manner, content, and result of

this struggle continuously underwent

modification and reformulation in different historical

junctures, according to the balance of

power

between the

main actors involved,

namely the

Oil Company

(whether

owned by the British, made of a consortium

of

several multinationals together with

the central state,

or nationalized and wholly

state owned), the central

state, and the resident population. This

ongoing struggle meant that the geography

of the city,

as well as its

identity, its

culture, and the social

and political

aspirations and abilities of its component

parts were continuously changing and

being overhauled.

The importance of Abadan and Masjed Soleyman

in the history of modernization, contemporary

urbanization,

and modernity

in Iran

are undeniable,

even if history has not been especially

kind to these

cities and their population.

Perhaps

there is some truth to the stark warning

of the journal 'Iran-e Farda' that

today's Masjed

Soleyman

offers

an image of the

whole country's

future without oil. The importance of Abadan and Masjed Soleyman

in the history of modernization, contemporary

urbanization,

and modernity

in Iran

are undeniable,

even if history has not been especially

kind to these

cities and their population.

Perhaps

there is some truth to the stark warning

of the journal 'Iran-e Farda' that

today's Masjed

Soleyman

offers

an image of the

whole country's

future without oil.

But, precisely

for the same reason, the story of these cities

cannot

and

should not be

limited to

the fate

and the narrative

of oil

revenues alone. Instead, the crisis-ridden

and troubled history and geography

of these company

towns must

be rescued from

oblivion, as

every detail

of their story holds precious lessons for the society's present dilemmas >>> Endnotes

>>> Page

1

About

Kaveh Ehsani is a member of the editorial

board of Goft-o-Gu quarterly (Tehran). This paper

first appeared in the International

Review of Social History (IRSH 48:2003, pp.361-399). Earlier

versions of this paper were presented to Middle East Studies

Association, 1998, Chicago; and at the conference on 'Iran:

Social History from Below', at the International Institute

for Social History, Amsterdam, in 2001. A written version in

Persian was first published in Goft-o-Gu (No.25, 1999).

He would like to thank Touraj Atabaki, Norma Moruzzi, Setenyi

Shami, Morad Saghafi, Ahmad Maydari, and Kaveh Bayat for their

intellectual influence, comments, and friendship. *

*

|