|

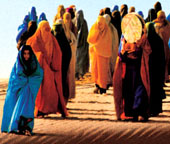

By Sima Saeedi This article originally appeared in tehranavenue.com. So, Kandahar too is now free. The Taleban have taken refuge underground and the people of Afghanistan wish upon Molla Omar the same terrible death inflicted on Najib Ollah. Reconstruction efforts have begun, despite the fact that the flames of war are still ablaze. And still, Afghan children remain hungry and Afghan women don't wholly believe that they can take off their Burkas. For over two decades now, Iran has been host to its Afghan neighbors fleeing war. We have not always been kind, but, as of late, we have become very kind. Our people and our artists have become kinder indeed, though each in their own ways. The Afghans who sought refuge within our borders had not seen the silver screens of the cinema for years. But due to auspicious occasions brought about after the events of September 11th, and the military intervention of the US and UK in Afghanistan, those Afghans, housed in refugee camps near the Iranian border, were given the glorious opportunity to look up at radiant faces adorning movie screens. The rest of the world too was not unkind. Several well-known filmmakers and stars generously donated a portion of their earnings to the Afghan cause. But, we don't have to travel too far, as last year two well-know Iranian filmmakers chose the Afghan cause as subjects for their films, one of them being none other than Mohsen Makhmalbaf, who, with his film Kandahar, has now become a world traveler. What does Kandahar give its audience? To watch Kandahar is not to travel to Kandahar at all. Even the traveler to Kandahar, at the end of the film, has yet to reach her destination. Instead, she remains close by, in the desert lands that start in the eastern most part of Iran and end in the most western part of Afghanistan. Suspended between a documentary and a docudrama, Kandahar leaves the viewer angry and disappointed. But, if you are looking for symbols, then this film will indeed amuse you. Perhaps, through use of symbols, the film is indeed successful in accomplishing one thing -- perpetuating stereotypes that exist in the mind of viewers. The heroin of the film is a female reporter, schooled at an elite university in the West, who sets out to reach Kandahar in search of a sister who has lost her leg in the mine filled lands of Afghanistan, and who plans to take her own life during the next eclipse of the sun. Nafas ("Breath" in Persian) is determined to bring hope and new life to the empty spirit of her sister. She begins her journey to Kandahar in search of excuses that could turn death away from her sister's doorstep. Khak ("Earth"), a boy who has been turned away from the religious schools of the Taliban, due to his lack of talent in Qoranic incantations, becomes Nafas' guide, so he can take her to visit a traveling doctor. The Doctor takes Nafas into the desert (!) where two European women running a Red Cross camp bestow artificial limbs, upon limbless men, who represent millions of Afghanis victimized in the endless minefields of Afghanistan. It seems that Makhmalbaf's impressions of Afghanistan are supposed to reach their highpoint and leave the viewer mesmerized in a scene where limbless men, with their eyes glued to the sky, run to claim flying limbs being dropped by parachute from the sky. But, before this happens, one nagging question emerges in the minds of viewers: "On whose limping strides does Makhmalbaf intend to travel the world?" *** Logic in the film Kandahar, unlike the Burka of Afghani women, has a colorless presence. Only symbols, haplessly placed, one next to the other, are offered to the viewer. Nafas, played by Nilofar Pazeera, who has lived abroad for some time, views Afghanis from an elite and Western perspective, as she attempts to buy her people, one by one, with the American dollars she has brought from abroad. Unfortunately, it seems that the Afghan people are only a means by which Nafas can reach her dying sister in Kandahar. There is little emotion or connection on the part of Nafas toward her land or her people. The character is indeed so disconnected from her country and her culture, that she records messages in English for her dying sister in the hand-held tape recorder she has taken with her on her journey into Afghanistan. Perhaps this too results from the Director's overwhelming desire for international recognition. Pain and suffering, after two decades of war, have perhaps seeped to the core of the being of the Afghan people, but not in the same manner as expressed in the film. It is with great audacity that Makhmalbaf attempts to portray, through a scene where Khak steels a ring from a corpse, an Afghani populace who have become numb to the misery of death and killing. What Makhmalbaf fails to portray is the fact that one can never become numb to the destruction of war, the destruction of death and killing, even in a place that has endured more than its share. At the same time, Makhmalbaf asks viewers to suspend their disbelief and to believe that a woman who would be so daring as to travel into the minefields of Afghanistan, into war torn territories, would be so faint hearted to be frightened by the sight of a ring stolen from a corpse, and to be bullied by her young guide. Though Kandahar is now enjoying world fame, it presents a superficial view of Afghanistan and the struggle of its people, so much so that it is indeed offensive. Over reliance on symbols, waters down the complexity of this ancient land, especially the tribal distinctions that are a hallmark of Afghanistan. The Afghan actor of the film too views her land with the same perspective as that of the Director-a Director who was the creator of some of the most daring post revolutionary Iranian films. The fact that Makhmalbaf has chosen not to travel into the depths of the spirit of the Afghan people, their struggle and their resistance, in light of this director's past achievements, is indeed perplexing to the Iranian viewer. Why is it that Makhmalbaf remains content with presenting the brave, hidden, and enduring struggle of the Afghan people through the insufficient representation of only one single scene where the Taliban confiscate a book and musical instrument, being unlawfully smuggled by guests at a wedding procession? The superficial view of the Afghan struggle in Kandahar leaves the viewer thinking that perhaps Makhmalbaf's view of the Afghan people is based solely on the image of the Afghan laborer in Iran, who has often been forced to endure misery and humiliation. Has Makhmalbaf forgotten that many of these Afghan laborers have chosen the humiliation that is part and parcel of the lives of common laborers in Iran and the displacement brought about by refugee life, as an act of resistance, a refusal to serve in the army of the Taliban? The beauty of Afghanistan is in the quiet and enduring resistance of the Afghan people -- a resistance which until very recently was fought in solitude and silence. *** Last year, a young photographer captured the image of an Afghani refugee family-a mother and father and their six children-living in the south of Tehran. He explained that the couple, both physicians, are parents to six illiterate children. I could not help but to laugh when I heard that the Afghani people, due to the generosity of Makhmalbaf, would become the proud owners of a school named Felini in Kandahar. In our country, where directors, because they continually capture images of destitution and suffering are being awarded international prizes, Afghan children remain illiterate. So, what do we tell these children? Should we tell them that they must remain illiterate until Kandahar is set free? Until a school by the name of Felini is built? Until they are able to return home and register at the school of Makhmalbaf? (In those days Kandahar had yet to be set free.) Makhmalbaf offers a literacy program through which every Afghan child, in a minimal amount of time (five-ten months), can become literate. Nabi Khalili, an Afghani journalist, in an article, titled, "Your Program Only Masks the Pain," published in Entekhab Daily on November 27th, 2001, while thanking those who are empathetic toward the problems of the Afghani people, provided an analysis of Makhmalbaf's literacy program. "I wonder how much of the attention being paid to the Afghan situation," Khalili asks, "is real and how much of it are motivated by political considerations?" We can assure Mr. Khalili that our Director has demonstrated on several occasions that he is indeed apprehensive toward politicians, but that he has been swept by waves of empathy now awash. *** It may be appropriate here to discuss a documentary by Sayareh Shah, an Afghani journalist, who resides in London, in which daring journalistic quality is apparent. She begins her journey to Afghanistan, by capturing onto film the demonstrations of Afghani feminists in Pakistan. Shah truly travels to the depths of the war torn cities of her country and brings to the viewer images of underground schools where education is provided to girls who have been banned from public spheres and takes us to the home business of a hairstylist in Afghanistan, who while applying makeup to the face of her customer, says: "this is how we resist." Life amidst death, reconstruction amidst destruction, this is the long tradition of the Afghani people. Shah does not have an elite view of her people and of her country. She literally travels among her people from behind the cover of a Burka and not the closed or open lens of a camera. Her work, while not being free of flaws, does not claim to be an artistic representation of Afghanistan. At the same time, it offers the viewer a much better representation of Afghanistan, than Makhmalbaf's Kandahar-which seems to speak more of the director's desire for fame, than on what truly goes on in Afghanistan. *** Many of us reminisce about the days when we would wait, heedless of the cold and rain, in the long lines outside Cinema Azadi, to see and hear anything that Makhmalbaf had to say. Now, he appears calmly and dignified on stages in Paris, London, and Venice and we can only be proud. He doesn't speak to us anymore. He is an international star and what he says addresses his international audience. If we criticize or object, we are immediately labeled as envious -- which is indeed what we are. We are envious of all those people who are viewing Makhmalbaf's work for the first time. They have never had to endure the cold of Tehran in February*, and they get to watch Makhmalbaf's work, now a world-renowned filmmaker, from the comfort of standardized seats in luxurious theatres. And, so why shouldn't we be envious? We wish him good luck and for ourselves we hold on to the memories of those cold days, when we took refuge in the warmth of Cinema Azadi.

|

|

|

Web design by BTC Consultants

Internet server Global Publishing Group

Hapless symbols

Hapless symbols