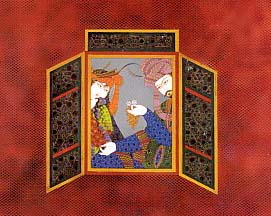

Painting by Farah

Osouli

Unparalleled genius

That is Nizami Ganjavi

February 22, 2001

The Iranian

From The

Poetry of Nizami Ganjavi: Knowledge, Love, and Rhetoric, ed. a Edited

by Kamran Talattof and Jerome W. Clinton (New York: Palgrave, 2000).

From The

Poetry of Nizami Ganjavi: Knowledge, Love, and Rhetoric, ed. a Edited

by Kamran Talattof and Jerome W. Clinton (New York: Palgrave, 2000).

The work of Nizami Ganjavi, one of the great Persian poets, has achieved

enduring significance. The five long poems, known collectively as the Khamsa

(Quintet) or Panj Ganj (Five Treasures), composed by Nizami in the

late twelfth century, set new standards in their own time for elegance

of expression, richness of characterization, and narrative sophistication.

They were widely imitated for centuries by poets writing

in Persian, as well as in languages deeply influenced by Persian, like

Urdu and Ottoman Turkish.(1)

Nizami's unparalleled genius was mirrored in equally

exceptional personal qualities. As E. G. Browne expressed it, "He

was genuinely pious, yet singularly devoid of fanaticism and intolerancehe

may justly be described as combining lofty genius and blameless character

in a degree unequaled by any other Persian poet." (2)

A year does not go by without the publication of a new book or article

about his poetry, and although he belongs to the classical period of Persian

poetry, the interpretation of his work has fueled a cultural debate in

Iran in recent years. For these reasons, a reexamination of Nizami's work

would be important.

The introduction to the book argues that more than jurisprudence issues

or any other religious concern, Nizami was preoccupied with the art of

speech itself. For him, the art of speech was the sublime. Furthermore,

departing from a Manichaeist or Zoroastrian dichotomy of good vs. evil,

he subverts the dichotomy of love and morality by presenting both as good.

In addition to articles by the editors, the volume includes essays from

prominent scholars of classical Persian literature. The articles included

illustrate not only the great diversity of Nizami's ideas but also his

underlying and overwhelming preoccupation with the art of speech.

In "A Comparison of Nizami's Layli and Majnun and Shakespeare's

Romeo and Juliet," Jerome W. Clinton draws attention to the very different

approaches taken by Nizami and Shakespeare both to describing passionate

love itself and to showing the impact of lovers on their communities.

In "Layla Grows Up: Nizami's Layla and Majnun in the Turkish Manner,"

Walter Andrews and Mehmet Kalpakli argue that Fuzuli's Ottoman Turkish

version of the story should be read as a revisionist interpretation of

the legend that gives Layli new prominence.

Kamran Talattof provides a comparative study of Nizami's work in his

article, "Nizami's Unlikely Heroines: A Study of The Characterizations

of Women in Classical Persian Literature," to further better understanding

of the attitudes of Nizami, Firdawsi, and Jami toward issues of gender.

Asghar Abu Gohrab in "Majnun's Image as a Serpent," argues

that in contrast to the early Arabic sources that refer cryptically to

Majnun's emaciated body and his nakedness, Nizami uses images of the serpent,

among others, to depict Majnun's physical appearance and his complex character.

Julie Scott Meisami devotes her paper, "The Historian and the Poet:

Ravandi, Nizami, and the Rhetoric of History," to a discussion of

Ravandi's use of quotations from Nizami in the Rahat al - sudur .

J. Christoph Bürgel, in his article "Occult Sciences in the

Iskandarnameh of Nizami," discusses Nizami's portrayal of an ideal

statesman based on Farabi's concept of political philosophy.

According to this book, in addition to military, political, philosophical,

and prophetic faculties, a statesman should also understand, among others,

astrology, alchemy and magic, and music and medicine-in other words, the

three major branches of the so-called occult sciences.

In "Nizami's Poetry versus Scientific Knowledge: The Case of the

Pomegranate," Christine van Ruymbeke explains Nizami's knowledge of

pharmaceutical and medical properties and uses by examining his remarks

on certain plants.

Firoozeh Khazrai, in "Sources of the Musical Sciences in Nizami's

Work," propounds the belief that men of Nizami's stature were conversant

in most of the sciences of their time, including music. She analyzes the

story about Aristotle and Plato as a point of departure for speculating

on some sources of the musical sciences of Nizami's day.

In his article, "The Story of the Ascension (Me'Raj) In Nizami's

Work," C.-H. De Fouchécour argues that Nizami has used traditional

material belonging to the prevalent religious discourse of his time to

create magnificent metaphorical expressions, entirely poetic and complex.

Because of this literary richness, Nizami's work has invited numerous adaptations.

Finally, the bibliography on Nizami's work will provide essential information

about the translation and scholarship of Nizami's work in several Western

and non-Western languages.

Purchase this

book

Endnotes

To top

1- No exhaustive reckoning has ever been made of the poets in Persian,

Turkish, Pashto, Kurdish, and Ordu (and other languages of the Persianate

tradition) who emulated Nizami's example by imitation, but by all indications

the figure must be staggering. The extraordinary dissemination of Nizami's

panj ganj throughout Persian and Persianate literature is a remarkable

and largely unexplored phenomenon (cf. Jalal Sattari, note 22 below, page

18). In the present volume J. S. Meisami opens up a new approach to this

question by examining the impact of Nizami's poetry on the Iranian historian

R?vand?.

To top

2- E. G. Browne, A Literary History of Persia (Cambridge, 1964) vol.

2, p. 403.

![]()