For the life of

a child For the life of

a child

Polish World War II refugees in Iran

By Robert D. Burgener

November 4, 1997

The Iranian

Filipina Stadnicka sat next to the hospital bed and cradled the

hand of her seven year old daughter Zofia. The sun was rising

over the hospital for Displaced Persons located northwest of Tehran

in a sparsely settled area that didn't even have a name. The

doctor

had told her the child was dying.

Most of the patients, former prisoners of war who ended up in

Iran after the Soviets released them in 1941, and the staff of

Polish

doctors and nurses had left. It was a year now since the war

had ended and those who weren't afraid of the communists had gone

back

to Poland, others had left for new lives in Mexico or any country

that would take them.

Filipina, her mother and father and young daughter had stayed

in Tehran living in a single room they rented from a family on

Nahid

Street. Filipina had a job teaching at the French School. She

had been a teacher back home in Poland until the summer of 1939.

Zofia was three that summer when they left for a short vacation

at her parents' home in eastern Poland near the Ukrainian border.

Filipina's husband was the police commissioner for their region

in western Poland and had no free time, so she and "Zosha" went

alone. The morning they were preparing to leave, news came that

the Germans had invaded Poland and within days they heard bombs

falling near her parents' home. Not from German guns.

The Soviet Union had invaded Poland's eastern frontier. Her husband

had managed one phone call to her after the surrender to Germany.

He and other prisoners of war were being taken to a place called

Katyn. She never saw her husband again. In 1941 she and the rest

of the world learned that the Soviet army had massacred 4,000

Polish military officers and civilian officials in Katyn forest.

She looked down at her daughter's unconscious face. So much had

happened to them. The knock on her parent's door after midnight

and the Soviet secret police giving the family one hour to gather

their belongings. Being loaded into the cattle cars of a train

headed east for the steeps of Kazakstan and the labor camps and

finally Comrade Stalin's announcement in 1941 that they were

free to go home - but what home.

The trek across the Caspian to Iran with her mother and daughter

, following in the footsteps of the re-constituted Polish Army

which had been sent to Iran to guard the oil fields, had been

marked with one of the few joyous moments of the war years when

they discovered

that her father and brother were alive and the family was reunited.

Now, this. Two days before, she and Zosha were crossing a street

in Tehran enroute to school when the Iranian Army truck came

round the corner and struck them. Filipina's injuries were not

serious

but Zosha's young body was badly broken and the doctor said that

without a new miracle drug called penicillin, the infection that

was spreading would kill her.

When Filipina arrived at Nahid street

several of her Iranian neighbors had gathered to offer condolences

and help. Shoja Ashrafi, a Captain

in the Iranian cavalry, lived just up the street and he and Filipina

had managed to exchange a few words in French since she could

not speak Farsi and he didn't know Polish. She shared the grave prognosis and the doctor's comment about

the miracle drug. It was Friday, the Moslem sabbath, and she knew

it

would be impossible to find anyone at the Ministry of Health

and that was the only place that could distribute such new and

scarce

medications.

Returning to the hospital, she sat between her daughter's

bed and the open window. A cool evening breeze had begun to ease

the stifling

heat and as she leaned closer to the window she heard the sound

of horses' hooves. She looked out to see Captain Ashrafi and

his sergeant galloping toward the hospital.

The doctor, accompanied by Captain Ashrafi, burst into Zosha's

room and announced that at last they had penicillin.

The young Captain, had rode to the health minister's home where

he shared his concerns - evidently in a most convincing way. The

Minister went to his office and removed one of only four vials

of penicillin in all of Iran and gave it to Captain Ashrafi - "for

the life of a child."

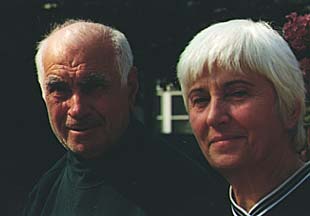

Captain Ashrafi & Zofia Jozefowicz-Niedzwiecka

Zofia Jozefowicz-Niedzwiecka returned to Poland to attend university.

She went on to be a senior interpreter for the Polish Parliament

involved in many high-level exchanges between Warsaw and Tehran.

She retired from the Persian studies department of the University

of Warsaw.

Captain Ashrafi and Filipina were married in Tehran and had three

children of their own. One son and a daughter are successful

business executives with American companies and another son is

a justice

on the New Jersey Supreme Court. Mrs. Ashrafi died on August

1st of this year while visiting Zofie in Warsaw. Copyright Robert D. Burgener. Permission to reprint given to The Iranian.

For information on a documentary video on this almost-forgotten

chapter of World War II, see "Tales

of the Persian Corridor - Bridge To Victory".

* Send

this page to your friends

|