|

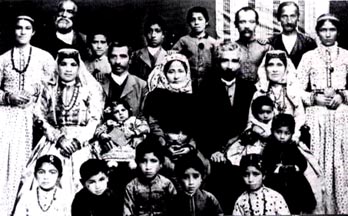

TAbrahamian

family from New Julfa, Iran, 1894.

From "Armenia: Memories of my home"

by Margaret C. Tellalian Kyrkostas

Last call

After four centuries, Armenians of Shazand are no more

By Behrooz Parsa

May 15, 2002

The Iranian

Call it anything you like. It won't make it any easier to bear. I am writing from

the town of Shazand, 20 miles southwest of the city of Arak, about 200 miles southwest

of Tehran. Years ago when I was growing up here, this town was basically made up

of four villages, a railroad station and a sugar mill. Two of the villages, Kelaveh

and Abbasabad, were mainly populated by Armenians.

The total population of Shahzand at that time was probably 3,000, with about 20%

to 30% Armenians, who since the early 1700 had gradually settled here, possibly because

Shazand was along their rout from Isfahan to Armenia, before modern roads were built.

Most of them were farmers. Some worked in the sugar mill. Others grew grapes and

made wine. They also owned the only tavern in town. They were part of the solid fabric

of our community, although they very much kept to themselves. We knew them not as

Armenians but as Mr. so and so, Mrs. so and so, fellow farmers, owner of so and so

farm or vineyard.

I left here when I was 15 to go to high school in Tehran.

I had planned to come back here, and become a schoolteacher, but I never did. I left here when I was 15 to go to high school in Tehran.

I had planned to come back here, and become a schoolteacher, but I never did.

After more than 30 years, I am back for a brief visit. Shazand is a much bigger town

now, almost a small city of 15,000 people. All 4 villages, the sugar mill and the

train station are clumped together to make up this not-so-attractive town with absolutely

no character.

The old sugar mill looks rustier than ever. There is little sign of the vineyards

and the surrounding miles and miles of farmland. There is an oil refinery, a petrochemical

plant, a 1,300 megawatts thermal power station, and a paint manufacturing plant,

all built over the past two decades, which have replaced the vineyards, and wheat

and alfalfa fields.

The air that used to be filled with the fragrance of wild roses (gol-e mohammadi)

and the freshly cut clovers is now filled with yellow smoke, and the smell of gases

and chemicals.

The other night, in my sister's house, while in bed, trying to go to sleep, I reached

and picked up the telephone directory of Shazand. Like Dustin Hoffman in the movie

"Rain Man", I started glancing through it, looking for familiar names,

old classmates and other folks I used to know here.

I didn't see the name of any of my Armenian classmates or their families. The more

I looked the less I found. There were around 3,500 names in there. I spent over an

hour and looked at every name. I was amazed to find out that there was not a single

Armenian name in the entire directory. I realized that after almost four centuries

of history in this part of the world, Armenians of Shazand were no longer here, finished,

gone, vanished, didn't exist anymore.

They had left behind, their farms, their homes, their churches, their cemetery, the

headstone of their ancestors, and gone away, as if they had never been here, as if

this place meant nothing to them.

That night, I felt strangely depressed. I didn't know

what was bothering me. I had left this place too, so did many of my other friends

and relatives. For some reason those didn't bother me. But just the thought that

a whole group of people had collectively decided to call it quits made me despair.

It was as if a universal law had been broken. I felt as if these people had betrayed

this land, or perhaps it was the other way around, this land had betrayed these people. That night, I felt strangely depressed. I didn't know

what was bothering me. I had left this place too, so did many of my other friends

and relatives. For some reason those didn't bother me. But just the thought that

a whole group of people had collectively decided to call it quits made me despair.

It was as if a universal law had been broken. I felt as if these people had betrayed

this land, or perhaps it was the other way around, this land had betrayed these people.

Now I am standing here on the slope of Mount Rasvand on the southwestern edge of

the town. The Ahvaz-Tehran passenger train is leaving the station heading north to

Tehran. The chimneys of the oil refinery and the power station are sending yellow

and blue smoke up into the sky. The sun is shining majestically overhead. I look

at the town and think to myself: "All gone, the wheat and alfalfa fields, the

vineyards, the Armenians, and the small tavern where I had my first glass of wine."

|

|

|