In 2010 James Dolan, chief executive officer of Cablevision got paid about $13 million, or about 400 time the wages of an ordinary you and me. By comparison the manager of the royal household of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great was paid 700 sheep, 600 loads of flour, and 32000 liters of beer and wine. This is about 100 times the wage of an ordinary Achaemenid postal worker (courier). Never mind how much Darius got paid—the king was a national symbol, and therefore beyond labor pricing–but when it comes to income disparity Achaemenids seem to have the U.S. beaten four to one in terms of social justice. How do we know how much workers and top administrators got paid during the Achaemenids?

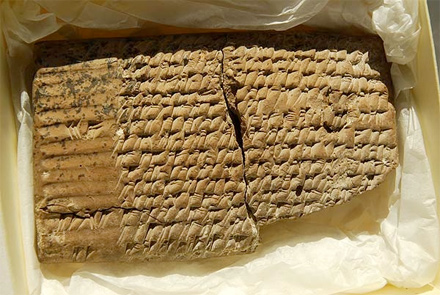

The information comes from deciphering a fraction of the 12000+ clay tablet “file cabinet” found at Persepolis circa 1930, and now stored mostly in the U.S. These are the famous Persepolis tablets now facing death by lawsuit in the U.S. legal system. The U.S. says the IRI is a state sponsor of terrorism and therefore U.S. citizens can sue Iran for injury resulting from IRI sponsored terrorist activity. For example, if Hamas hurts an American citizen during a terrorist attack, the injured person can sue Iran for supporting Hamas’ act. In fact many plaintiffs have already won large damages against Iran; the only problem was how to collect the court awarded money. After some hunting around in law books, they found out that a loophole in the 2002 Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) allows them to auction off the Persepolis tablets housed in U.S. universities. That should raise a few million, they thought.

But just last week the NIAC news email brought good tidings that some of the tablets have been rescued, apparently through clever use of a legal technicality. Lawyers defending the tablets in Massachusetts successfully argued that the plaintiffs couldn’t prove that the items actually belong to the IRI. To get more detail on the temporarily good news I talked on the phone with NIAC president Trita Parsi. NIAC has been involved in the tablet rescue efforts, leading where it can and assisting where it can. When I asked what would happen to the tablets if they were auctioned, Parsi’s typically measured interview voice became troubled:

“When you have a lot of artifacts–as we see in this case–the relative market value of each item drops. And as has happened before, the business owners destroy many of the items in order to increase the value of the remaining ones. We have seen this happen with Egyptian artifacts in the past. There’s a significant risk. It may actually happen that there will be a deliberate effort to destroy the stocks to make sure that the remaining 500 out of the 12000 fetch the best price! Then this part of our history and heritage will be destroyed.”

This is simply barbarism, committed in the name of 21st century justice. From a perfectly reasonable angle these tablets are just as important as the Darius Behistun inscriptions or even the Cyrus Cylinder. Why? Because archeological sites and museums are full of self-descriptions by rulers of what kick-ass heroes they were and how justly they ruled. Bein e khodemoon, “Cyrus Cylinder” kings were a dime a dozen. Even today, Kayhan is a daily Cyrus Cylinder made out of paper. To give substance to our past we need more than the words of Cyrus and Darius; we need to audit their receipts. And this is precisely what these tablets are: receipts, invoices, pay stubs, wage tables, reimbursement, how much food and wine the priests of different religions got to offer their gods, etc. sampling several periods of Achaemenid rule. So far the tablets reveal an empire buzzing with a complex economy, an active society and run by an intricately structured administrative system. There’s an astonishing amount of detail about Achaemenid life in these tablets, beyond what we could have reasonably hoped; their discovery is a cultural windfall for Iranians. Ironically if it hadn’t been for another barbaric act—Alexander’s–more than two millennia ago, these tablets may have been scattered centuries ago. The quick collapse of the Persepolis building hid the tablets and made them inaccessible.

Despite the recent victory in Massachusetts, the bulk of the tablets in Chicago and elsewhere in the U.S. are still very much in danger. NIAC’s main effort has been to participate in legislative efforts to help close the loophole in the law. Museums, libraries and universities are unhappy with TRIA language that allows cultural artifacts to be legally regarded as commercial goods. Already some countries are refusing to loan artifacts to U.S. cultural and educational institutions because of the risk of their being confiscated through lawsuits and auctioned. And already there are indications that the U.S. may face treatment in kind from other countries. These are the cultural dangers of trying to run foreign policy through domestic laws. Since NIAC’s area of expertise is in dealing with Washington, the organization is a natural fit for the Iranian-American contribution to amending the poorly phrased TRIA language. Here, paraphrased, is the amendment NIAC is supporting:

The property of a foreign state or of an agency or instrumentality of a foreign state shall be immune from attachment and from execution if the property—

1. is cultural property.

2. is in the possession, custody, or control of any museum or library, or institution of higher education.

As another effort NIAC also helps with the defense in court cases. Since NIAC is neither the defendant nor the plaintiff in such cases, it can only act as an interested third party to educate the judges with “friend of the court” briefings. Here’s a link to a 15 page NIAC “friend of the court briefing.” Besides citing various court cases and international precedents regarding the immune status of cultural property, the brief explains why the organization is interested in the case:

“These artifacts have substantial historical importance and have value to both scholars and ordinary citizens seeking to understand Iranian history and culture. Even to the extent that the artifacts are legally owned by the Government of Iran, they do not fully belong just to it. They are part of the cultural heritage of all persons of Iranian descent.”

Parsi mentioned a third approach which at first sight seems softer, but on deeper thought is the biggest battle in rescuing our heritage. NIAC has been an active participant in the cultural events of other organizations–such as the Parsa foundation–to promote a higher understanding of the preciousness of our culture. Without a community awakened to its own worth, judicial and legislative efforts are meaningless. The Iranian-American public has to care, or these tablets are just what they look like: old clay that is somehow worth millions to “crazy foreigners.”

Quite aside from fear of losing a valuable part of humanity’s heritage, as an Iranian-American confident of Iran’s historic and cultural worth, I am angry and indignant at this insult of U.S. law to the heritage of other nations, in particular Iran. How dare they try to cash in on what Darius and Xerxes left us!?

I wonder how many other Iranian-Americans are just as displeased.