Shirin Neshat at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C.

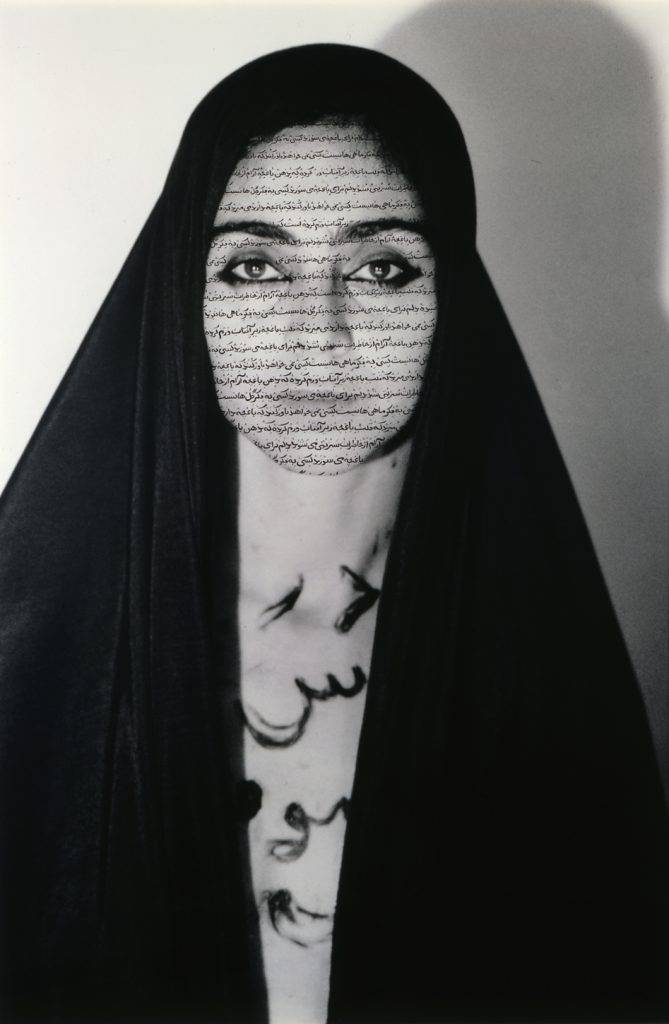

When you catch the right wavelength that communicates the nuances of a vast and varied culture to a wide global audience, you want to grasp onto it. Shirin Neshat, one might say, has achieved this; and, in the past two decades, she has become an icon of contemporary Iranian – and Middle Eastern – art in the process. You may have seen Neshat’s characteristic images before: large, evocative, black-and-white photographs with Persian calligraphy inscribed on them, many of which show women in veils holding weapons, at times powerful and aggressive, and at others, withdrawn and submissive. Her current major exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., however, will mark the end of this chapter in her career, according to the artist.

Shirin Neshat: Facing History is the Museum’s first major show of a female artist of Middle Eastern descent in a considerable amount of time, if ever. Curated and organised by Melissa Ho and Melissa Chiu, the Hirshhorn’s new Director, the exhibition follows the chronology of three pivotal moments in the history of 20th century Iran: the 1953 coup-d’état and overthrow of democratically-elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, the 1979 Revolution, and 2009’s Green Movement. Throughout, the artist’s work is annotated by three galleries displaying journalistic footage and photographs, as well as source materials, such as Neshat’s copy of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings) she consulted while working on her series of the same name. It is indeed a rare and precious occasion to also see leaves of Safavid-era miniature paintings from the Shahnameh displayed here on loan from the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries.

This is not, however, to ‘frame’ Neshat as a politically-charged and/or activist artist – labels the artist has repeatedly rejected outright. It is a fine line to walk on; on one hand, the documentary material shapes the way we see her work in showing the historical references that inform it, making her art appear documentary and topical in nature, and, potentially, her messages artistically limited. The Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott is one who has criticised such treatment of her work, suggesting, even, that the exhibition ‘threatens to make Neshat into a conduit, or worse, a martyr, of the tragedies of Iranian history’. Likewise, Hamid Dabashi, professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at New York City’s Columbia University, has gone so far as to condemn the curatorial reading as ‘clueless’. On the other hand, without the necessary context to overcome the gap between the artist’s intent and the possible reactions of uninformed viewers (e.g., with respect to the content of the scripts and the imaginary aspects of her practice), Neshat’s work runs the risk of being mistaken as representational and delineating; after all, the admission is free to the general public. According to Ho, the reference materials act as ‘scaffolding’ for the audience, in addition to serving to acknowledge the relationship between the artist and experienced events.

One cannot, it may be argued, disregard the impact of lived history on an artist’s work; and, further, isn’t one of the ‘purposes’ of art to respond to, challenge, complicate, and find renewed meaning in the world we inhabit? If so, then what differentiates any admirable art from ‘political’ art? Perhaps this curatorial approach in fact achieves much more than only providing context; it accentuates and interrogates the paradoxes that Neshat’s work is all about: reality versus imagination, Persian and religious values versus contemporary aesthetics, and East versus West (from a traditional understanding). The departure from reality observed in this body of work fulfills the countering and resistive purpose of the creative act – not only against social oppression and historical grievances – but also against reality and convention. This firm resistance is visible in Neshat’s consistent impulse to confront oppression and tragedy with beauty. In one gallery exhibiting works from the Women of Allah series, a hand-covered face is evocatively grouped with an image of a gun peering above a pair of open palms, and another of a mother – wrapped completely in a black chador – holding the hand of a child. Neshat was involved in such decisions of placement, and with her jarring position, has been able to further push and pull this dynamic of power and spin the orientation of reality versus imagination. ‘Art is a lie that tells the truth’, the artist often says, quoting Picasso.

Contemplating Neshat’s work against the backdrop of sociopolitical occurrences in Iran, viewers experience the allegorical and poetic world the artist creates to fill the void of distance, of inability – or rather, impossibility – to answer the unsettling political shifts and conflicting feelings towards new and adopted homelands. The artist did not experience firsthand these defining moments in modern Iranian history; born in 1957 in Ghazvin, Iran, she has been living in the United States since the age of 17, and only visited Iran a few times in the 90s. This nomadic sense of ambivalence and ‘in-betweenness’ is written all over Neshat’s work and biography, as well as her inclination to experiment with projects outside the ‘expected’ path of a visual artist.

The exhibition at the Hirshhorn comes at a timely moment, punctuating the end of a chapter in Neshat’s artistic career. As she herself announced, she intends to explore subjects beyond Iran, as well as other artistic forms. At the Museum’s ‘Meet the Artist’ programme, Neshat showed audiences a teaser sketching out ideas for her forthcoming feature film on the celebrated Egyptian singer Om Kolhtoum, in addition to mentioning an ‘epic’ opera project she has taken on. Indeed, Neshat in recent years has been turning to the wider Middle East outside Iran, challenging the boundaries that have defined her as an ‘Iranian artist’ who ‘makes work about political subjects’ or ‘works with photography and video installations’ in search of a sublime state unrestricted by the specifics of location and medium.

Neshat’s more recent work is reflective of her consciousness of a worldwide audience, and shows, in fact, a stronger inclination towards the fundamental emotional power of art that transcends national and cultural codes and forms. In the Our House is on Fire portraits displayed towards the end of the exhibition, Neshat – known for combining elements of literature with images – returns to her signature style of inscribing Persian calligraphy on photographic prints; but here, the writing blends into the wrinkled faces of the subjects, and the letters, written in different shades of ink, are layered on top of each other. Compared to the works in the Women of Allah series, the legibility of the writing is not as crucial here. The clearer Persian scripts are layered over fainter ones, imposed on lines carved by tragedies on pain-ridden faces of Egyptian parents who lost loved ones during the recent Revolution. Cultural and linguistic boundaries are further blurred and complicated, with a concept akin to that of opera: without understanding the precise meaning of the language, an artistic effect is still achieved because of a shared humanity.

If it is true, as Dabashi has passionately pointed out, that ‘entrapment within a commodified branding has forced [Neshat’s] art outside the metaphysics of its unprecedented power and audacity’, then perhaps the artist may regain her ‘metahistorical power’ and ‘aesthetic abstractions’ as she explores more transnational and transcultural topics, and further translates her visual eloquence into moving images with prominent musical elements. Speaking about music, Neshat once told Arthur Danto in a 2000 interview that,

I think music intensifies the emotional quality [of my art]. Music becomes the soul, the personal, the intuitive, and neutralises the sociopolitical aspects of the work. This combination of images and music is meant to create an experience that moves the audience.

Even before Neshat embarked on her opera project and Om Kolthoum film, music played a large part in her earlier video installations. In 1998’s Turbulent – also on view at the Hirshhorn – music composed by Iranian singer Sussan Deyhim becomes a central metaphor for the complexity of gender relations in Iran. Split between two channels projected onto opposite sides of the gallery wall, the male and female singers display a musical dichotomy. After the man (Iranian artist Shoja Azari), seen directly from the front, sings a song in the classical vein to an approving all-male audience, the woman – forbidden to sing alone in public in Iran – bends the logic of music and society as she sings to an empty auditorium. Without words, she begins with a low hum and moves astonishingly to unpredictable layers of guttural repetitions, shrilling howls, and rapid glissandos in a mystifying, melodic chant. Unlike the male singer, she appears to be driven more by overwhelming emotion than rehearsed, controlled technique; and, as her musical performance intensifies, the camera circles around her, showing partial views of her face, moving constantly. Her song progresses in a way that is at once strange, tender, and strident, and through her visceral and rebellious performance, she assumes power and triumphs, finding liberation.

Like the already-familiar application of literary texts in her work, Neshat’s activated interest in music – as an artistic tool, metaphor, and subject – shows the desire to communicate emotional power on a more universal level. Music in her work already conveys messages of opposition, peace, and freedom – qualities that arguably make her works a form of protest. In her forthcoming feature film and opera, music will hopefully act as more than a mere symbol, and rather, as a medium and artistic language unto itself; as well, it may, one hopes, achieve the intricacies and magnificence that give renewed and reimagined meaning to otherwise banal facts and chronologies. And so, without being pigeonholed as political, the value of her work may finally transcend beyond historical readings and commercial success to uninhibited art: that heroic, dissident lie that tells the truth.

‘Shirin Neshat: Facing History’ runs through September 20, 2015 at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C.

By Joan Hua

Originally published on REORIENT