به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Advertising “Religious Harassment”!

by Amir-Human Orfi

11-Aug-2009

A rather dense article of mine (in Persian) is now published on this site:

//iranian.com/main/2009/aug-14

I would like to give an outline of the main themes of this piece here.

The article’s title can be thought of as a translation of the English term “religious harassment”. In the above piece, I have tried to identify and isolate a concept and then use that concept to shed light on an important, omnipresent problem in Iranian society and culture that has not been dealt with before, to the best of my knowledge, in quite the same fashion. A Persian term is coined to refer to this concept and the resulting widespread problem that is so much part of our culture that is way too often taken for granted.

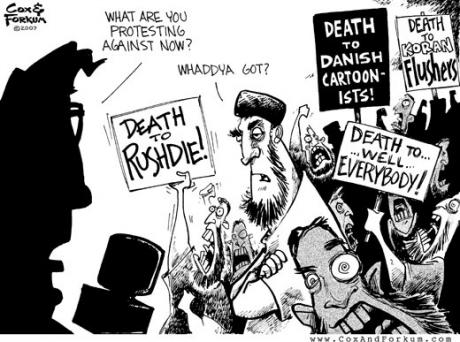

It is pointed out that religious harassment is not exclusively Islamic and other great religions have also gone through a phase where religious harassment has been dominant. Then a micro-history of religious harassment, Islamic style, since the birth of Islam has been offered and it is claimed that this practice has been instrumental in spreading the Mohammedan faith in the early centuries of Islam and has emerged in recent years as a method to protect and preserve that faith of the Muslims. (One important instance of religious harassment in recent years was Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie.)

To clarify my ideas, various aspects of this problem have been discussed and a few important examples from a wide spectrum of this practice were listed. Religious harassment covers a wide range of practices. To give two examples from the opposite ends of this spectrum, one can cite the awkward atmosphere that is felt while religious and non-religious Iranians get together in a small semi-personal space, such as offices or gathering of relatives. In more explicit forms of this example, certain religiously sanctioned restrictions are imposed (such as women’s hijab) aimed at making the less religious individuals uneasy. This of course is a mild form of religious harassment, while “punishing” (in any way, shape, or form; e.g. killing) or even threatening to punish “the Other” simply because they do not believe in the religious dogma or do not act and behave in a way that is consistent with the teachings of mullahs belongs to the harsher end of this spectrum.

It is then pointed out that while religious harassment had been more or less in check in Iran during the Pahlavis’ era it has found a new life after the 1979 revolution. The fact that religious harassment has been nurtured, encouraged, and institutionalized by the Islamic regime since its inception has been briefly discussed, but certainly needs to be expounded upon further.

It is then shown that one can easily approach the questions of justice, freedom, tolerance, etc. from this particular point of view, that is, via the concept of “religious harassment”. It is not claimed that uprooting religious harassment will be tantamount to FULLY establishing justice and freedom in Iran. However, it is shown that a great host of ills of Iranian society can be easily explained by means of this notion. In other words, many instances of injustice, discrimination, and lack of social freedoms can be categorized under “religious harassment” and then hopefully dealt with by noting the widely varying forms of religious harassment that are so deeply rooted in the post-revolution culture in Iran.

There are more in the original piece (for example, a discussion about the roots of religious harassment, or the economic import of religious harassment for financial independence of Shia seminaries) that I am not including here, but this should be a fair description of the Persian version.

Amir-Human Orfi

August 11, 2009

| Recently by Amir-Human Orfi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

با مذهبى ها چه بايد كرد؟ | 2 | Jun 21, 2010 |

چرا سكولارها در ايران كامياب نيستند؟ | 4 | Jun 19, 2010 |

درباره ى مقاله ى اخير مصطفى تاجزاده | 3 | Jun 16, 2010 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

The topic at hand ...

by alborz on Mon Aug 17, 2009 08:12 PM PDT... is addressed in the "Resaaleh ye Madanieh" in the context of the influence of the ulama on Iranian society and their involvement in politics and its consequences. So this treatise along with one called "Resaale ye Siyasieh" is filled with examples. In fact the latter which is significantly shorter in length, can be read in probably less than 30 minutes and is more relevant to the topic at hand.

Resaale ye Siyasieh can also be found on the same page as the Resaaleh ye Madanieh.

Until later,

Alborz

Diversity, etc.

by Amir-Human Orfi on Sun Aug 16, 2009 04:27 AM PDTDiversity has its pluses and uniformity also has its own pluses, and the latter seems to be preferred by the leaders of great religions, but I think neither should be a goal of social change. However, in the complete absence of religious coercion the fractionalization of available formats of religion and coming-into-existence of new spiritual factions seems practically unavoidable. What's important is the ability of the followers of these diverse forms of religion to coexist peacefully. This is at times quite difficult, but not entirely impossible as the experience of great democratic traditions of our time have shown.

I have surely benefited from this conversation, and if that translates into major changes in the final draft of Part II of my essay I will certainly make sure to give you (Alborz) due credit.

Finally, thanks for sharing Abdu'l Baha's piece on Iran from around a hundred years ago. It should be an interesting read, as I've read about Abdu'l Baha that he has been an energetic, thoughtful and charsimatic religious leader (not to mention quite handsome in his youth and old age) in his time and I would like to someday read the Persian (original) version of it, but if there is any part of it that you specifically find relevant to our discussion, I'd appreciate it if you could copy and paste and email that part to me.

Have a safe trip, and we shall continue later.

Yes, I too hope that I am around ....

by alborz on Sat Aug 15, 2009 03:20 PM PDT... when that day arrives.

Your noble intent in this dialogue is abundantly clear and I am glad that we have engaged in this discourse. While the possibilities are numerous, the intent is the same - to see a mature society that respects the views of others and values diversity as a necessary component for growth and advancement. The old adage "aab raaked bemooneh migandeh" really applies here.

While I may have detracted from your focus on Part 2 of your blog, I hope that it has served you well in creating its final draft.

Thank you for your compliments - I have to say that I wish I could write like you do in Persian.

You have now assigned some homework to me that I need to attend to before I leave for trip.

Best Wishes,

Alborz

PS- How did you finally format the text, as I have never been able to mix Persian and English in the comment section. I have been able to do it in the main blog by first typing in Word and then doing a cut and paste - but that does not seem to work in the comment section. Just curious.

PS- About a 100 years ago, Abdu'l Baha, the eldest son of Baha'u'llah wrote on the subject of Iran under the title of "Resaale Madaniyeh" and when it was translated into English it was entitled "The Secret of Divine Civilization". Both are available online. In it he describes the state of affairs in Iran and counsels those in power at the time. You may find it engaging - keeping in mind when it was written.

//reference.bahai.org/en/t/ab/- English mid page

//reference.bahai.org/fa/t/ab/ - Persian on top of page

Alborz,

by Amir-Human Orfi on Sat Aug 15, 2009 02:10 PM PDTFirst, I'm sorry about the messed-up format of my previous post: this was caused by my insertion of a few Persian words in the middle of an English text!

I actually think the question of what would happen to Iranians' religious/spiritual orientation in the wake of a complete removal of "eeza ye dini" in the Iranian society is an interesting one, and in my draft to the second part (to be published in near future, I hope) I have speculated on a number of possibilities:

In the short run, a whole lot of people may renounce their "Muslim identity", especially given the forcefulness of a racist, anti-Arab culture in certain sections of our society. A lot of people would still remain Muslims, of course, because although it would not be necessary to sign the official forms as Muslim anymore, there will be other obstacles that would make it inconvenient for them to leave the faith. For example, men may still want their wives and daughters to obey them and they like how Islam makes it easy for them to justify and sanctify their sexist urges, or some would think that an explicit exit from Islam would cause family feuds that's probably not worth it, etc.

In other words, the "geography" of Iranians' faith will go through important changes. Some Iranians may explore other avenues for satisfying their spiritual needs, as some are doing already in fact. (There is a proliferation of new age type sects and various Islam-like offshoots have earned for themselves followers inside Iran in recent years.) We may witness a "fractionalization" (to use your term) of Islam, the same way that Christian sects mushroomed in early American history.

In the long run, however, a religion that has lost its thirst for "eeza ye dini" may actually attract more Iranians, be it the mainstream Islam or various denominations of Islam or any other mixture of possible faiths. The possibility of having large number of small sects may seem as a perfect recipe for chaos, but if we look at the examples of democratic societies, from India to America, we see that as long as the principle of "No pressure in religion" (which is, quite ironically, advised in a verse of Koran!) is upheld (both by people and the government) no harm will be done. People will be free to explore and experiment with this or that faith, or simply stay out of it altogether.

This may all seem like wishful thinking, but I dare to dream it, even if on that day, many years from now, I may not be here to witness it.

Dear Alborz,

by Amir-Human Orfi on Sat Aug 15, 2009 12:45 PM PDTFirst of all, thank you for your kind words.

Your command of English is impressive. I very much agree with what you said in much of paragraphs 2-4 of your last post, and I couldn't have said it better myself. What I have said, however, is not a "new perspective" really, as I had pointed out, albeit extremely briefly, at the things you have well elaborated on in those paragraphs in the Persian version (Search for "صحت يا سقم" and "گروگان" and "فوج فوج" in the Persian piece), but I agree that they need to be expounded upon and I feel that people (myself included) should write about the issue of "eeza ye dini" and how a lot of Iran's social ills can be traced to it, and how this concept can provide a new framework for attacking a lot of Iranians' problems.

In writing about "eeza ye dini" what I have tried to convey (and I seem to have failed miserably, or at least would have failed had it not been for such critical conversations) has been this belief of mine that when the complete range of misdeeds that are instances of "eeza ye dini" are all recognized, not as isolated, unrelated acts that have to be attacked separately, but rather understood as various incarnations of one single evil by a large number of Iranian thinkers and laymen, then it will be easier for Iranians to reject this evil in all of its forms, pretty much the same way that when we see a larceny or burglary or robbery or embezzlement or other forms of theft, we readily recognize them as instances of an evil, i.e. theft, the evilness of which is already established, and condemn them not because they carry this or that specific names, but because we see them as instances of this single immoral act.

Until soon...

Moslem as an identity vs. Moslem as a believer

by alborz on Sat Aug 15, 2009 10:24 AM PDTLet me assure you that while I too am almost all spent in this exchange, it is by far one of the most pleasant exchanges I have had on this site, primarily because of the spirit in which it is conducted. Also, it is precisely the difference in our perspectives that I think makes this exchange rich and illuminating for me. So, thank you on both counts.

In your last comment, you introduced a perspective which I did not anticipate! That is, the distinction you have made between an Iranian who is a believer and one that is not. Furthermore you associated 'eeza ye dini' with a means for retaining Moslems within the fold.

I completely follow your logic and if I had learned of this perspective earlier in your narrative, I would have been able to more quickly appreciate where you were heading with this. The reality is indeed that when asked, the over-whelming majority of Iranians identify themselves as Moslem. But when asked whether they practice the tenets of Islam, a far less number would say 'yes'. Of those that say 'yes', a portion do so because of 'eeza ye dini'. Therefore if 'eeza ye dini' was absent then a shift in the numbers of practicing (belief) Moslem would occur towards non-practicing (identity) Moslems. In your comment you also imply that Iranians would leave Islam en mass. The question that arises is whether in the absence of 'eeza ye dini' would Iranians leave Islam to become people without faith or would they join other faiths. Would their new found freedom from the shackles of Islam now allow them to declare themselves faith-less?

I recognize that this is not the question that you are trying to address in your blog, but it is by extension the question that people would have to face. For this reason, I believe, that Iranians find safety and comfort in having the Moslem identity even though they struggle with it and would prefer to transcend it. They live with this dicotomy and therefore they remain hesitant to investigate for themselves. It is the one part of their identity that they reject privately but when filling out a government form they confirm, even when they live outside of Iran. Being a Moslem for many is simply an admission ticket, and a membership in a club that provides basic civil rights and more depending on their outward ferver. People understand how this works and gladly comply when there is a scarcity of resources and access to opportunity is contingent on connections and not merit.

I need not be convinced of the 'vileness' of 'eeza ye dini', but the context in which I advocate its absence, is through a fundamental change in perspective. That I am responsible for myself and cannot judge others in matters of faith. That I am repsonsible for my actions and its consequences. That the constitution and laws of the land need to safeguard the rights of its citizens, and its judiciary and law enforcement needs to uphold these laws. And the list can go on, but can we get there by making advancements in the degree to which a woman's hair is showing? This is why issues at the grass roots level will lead to wholesale changes at the top - sometimes it is called 'reform' and other times called 'revolution'. Mature democratic societies undergo reform regularly. I am, however, not aware of the potency of reform under 'ideological' forms of governance. The norm appears to be revolution, however, I will look into the link you have provided.

Finally, I don't consider the replacement of a Monarch with a Velayat Faghih was a cosmetic change. I know that many share your view but the by looking at the outcome, one is hard pressed to conclude that the two represent a cosmetic change. The implication of this view is that in 1979 we had a coup d'etat and not a revolution - that certainly was not the case.

Best,

Alborz

The "Bottom Up" Approach

by Amir-Human Orfi on Sat Aug 15, 2009 09:44 AM PDTAlborz,

A quick search led me to the following:

//www.amazon.com/Solutions-Social-Problems-Bottom-Successful/dp/0205468845

I have not read this book, so I don't know to what extent it is relevant to our discussion. There were many other links about "Bottom-UP Social Change", but I trust that you can find them using a search engine.

Regards,

A-H Orfi

P.S.

by Amir-Human Orfi on Fri Aug 14, 2009 04:01 PM PDTAlso, the fact that BCJZ folks have not voiced their objection to the imposition of the milder forms of "eeza ye dini" on them may be that they have accepted such "noise", if you will, as a fact of life, a fact of living as a religious minority under a religious regime. Such compliance and tolerance should not diminish the evilness of such harassment.

Dear Alborz,

by Amir-Human Orfi on Sat Aug 15, 2009 08:32 AM PDTThank you for keeping up with me in this interesting battle of ideas. I am almost out of breath now...

All right, let me address your first three paragraphs (in your latest post) as you seem to drift away from the main topic in the remainder of your comment to the realm of politics with which I will not deal presently. (I will try, however, to find an example of the proposed "bottom-up" approach to social change, which would require some work on my part as I am no sociologist either.)

You say that religious minorities in Iran (BCJZ) have not opposed to the "minor" cases of "eeza ye dini", because they have "bigger fish to fry", while it has been Muslims who have repeatedly objected to such harassment. In saying so, and perhaps without intending to, you accept IRI's definition of the term "Iranian Muslim", i.e.: Any Iranian who does not belong to BCJZ minorities.

This is a flawed definition. Many of us, the non-BCJZ folks, are not really Muslims by any stretch of imagination, and many more would simply stop being "Muslims" had it not been for the suffocating omnipresence of various forms of "eeza ye dini" in our society.

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that one day all forms of "eeza ye dini" are removed from the Iranian society. On that day, Iranians will be free to announce that they do not believe in Islam without fear of harassment, persecution and execution. What do you think would happen as a result of a complete removal of "eeza ye dini"? How many "Muslims" would choose to remain Muslims?

I do not know the answer to that question, but my point is, Acknowledge the vileness of "eeza ye dini" and then remove it from society and you will have real deep upheavals taking place, not just "cosmetic" ones, such as replacing Monrachy, in 1979, with Velayat Faghih.

Approach - continued

by alborz on Fri Aug 14, 2009 11:02 AM PDTLet me begin by saying that the perspective that I have shared with you is not one that I believe in dogmatically nor one that I am inseparably attached to. Far from it. I remain completely open to your views and receptive to your perspective.

What I have tried to do in our dialogue is to acknowledge the realities of our society with a particular emphasis on the degree to which those subject to what you call 'eeza ye dini' have suffered, and that 'approach' will determine when and if it will end, and not just become tolerable.

While the blasting of the 'azaan' from the local mosque's loud-speakers, or complying with a dress-code may fall into 'eeza ye dini', they don't DIFFERNTIALLY impede a citizen's ability to reach their full potential in that society. In the same way that extremes in climate across the inhabited parts of this earth create unique challenges, it does not differentiate between the inhabitants in opportunity to reach their full potential within that part of the world. Religious minorities have never, to my knowledge, objected to these types of 'eeza ye dini', while Moslems repeatedly and vociferously have. Religious minorities have in essence 'bigger fish to fry', such as civil rights.

Social change and transformation has been studied extensively and the 1979 revolution in Iran was predictable. In fact many had recognized the impending events as long as 3 to 5 years earlier and many more have written books on this subject. I am not a sociologist but I do believe that just as with any science, if you are gathering the right information and have the skill to analyze the relevant information, then it is possible to anticipate the outcomes. The question today is whether there are those that are both skilled and knowledgeable of the facts in that society. The answer may alas be no - once again.

I am not aware of any social change through the approach you are advocating. Far from disqualifying it on this basis, I simply ask that you offer such an example and then also take into account the heretofore unanticipated role that the Internet, Facebook and Twitter have played in the recent upheavals in Iran. If an 'ideal' is recognized by one or two generations of Iranians, I am hard pressed to believe that they will take 'baby steps' to set the stage for 2 generations later to achieve that 'ideal'. Social upheavals occur precisely because each generation wants that ideal for themselves and the generation after them (their children). They may have attempted it but the response to it has made them resolute in taking an alternate route. This is why I think social change is ultimately non-linear.

For these reasons, I remain skeptical of the validity of the linear approach. Just as pressure does not build up linearly nor does it relieve itself gradually once a crack has developed. Just recall the final days of the past regime and how rapidly event unfolded. Pressure has built up in our society and won't settle at a lower and more stable level. The world that Iran is part of is rapidly changing and the differential is the primary motive force for the upheavals. Those that are aware of the 'ideals' and are not 'brainwashed' enough to discount it, then will seek it. The harsh response we have witnessed over the past several weeks is born out of fear. Fear of rapid change and not gradual change. That should tell us something about how they view this phenomena.

Again, thanks for the thoughtful exchange.

Alborz

Continued...

by Amir-Human Orfi on Fri Aug 14, 2009 09:18 AM PDTI agree with you on the importance of the kind of approach we choose for attaining our goals. However, although I believe transforming Islam (the way Iranian or other “religious intellectuals” have attempted to accomplish, or in any other way for that matter) or transforming Iran’s governing system (either the way the so-called “opposition” in exile have been working on, or even the way Islamic reformists inside Iran hoped to accomplish prior to revelations after the June 12 presidential election) may be interesting endeavors in their own, I’m afraid they are not my primary concerns.

My philosophy of social change is more of a “bottom-up” nature. A “top-bottom” approach suits political-minded individuals who tend to hold the form of the government, and in particular a flawed legal system, responsible for social ills and who, based on this very assumption, seek to effect change, first and foremost, at the level of the ruling political elite.

While I do not deny the importance of the “system” at the top and deem transforming the regime a laudable goal, I am convinced that the more urgent task to attend to is change at the level of culture. In other words, if I may use a Persian proverb here, I am an advocate of patiently, yet persistently being at the business of amputating a cancerous organ “by cotton, rather than by knife”.

In my daydreams I envision an Iran where some sort of ethical principles detached from and independent of religion has taken strong roots in a critical mass of individuals (and not just a minority). One of the many pillars of such secular ethics would be rejecting “eeza ye dini” in ALL its forms, from systematic persecution of religious minorities to denying non-religious Iranians an equal opportunity in the job market and a range of discriminations against non-religious individuals all the way occasional harassing of people in their workplace or public space or even their own private houses (think of the loud speaker example in a previous comment I posted here).

I imagine an Iran where any attempt on the part of religious fanatics or religious institutions to harass or otherwise put pressure on non-religious Iranians or otherwise make their lives difficult JUST BECAUSE they do not subscribe to the official religious dogma will be automatically recognized by everyone as an instance of “eeza ye dini”, and therefore deemed unacceptable, outrageous, unethical, and hopefully, in not so-distant-future, even unlawful.

But this process should start, in my opinion, from a transformation in the perceptions of Iranians, and in particular what they perceive to be unethical and therefore outrageous and unacceptable, and then, if and when the waves of such an internal transformation reaches a big enough population of Iranians, we will be only a few short steps from the change taking place at the top. It may be my optimist self speaking here, but I would like to think that at some point change at the top will be inevitable, and the old system will easily crumble.

The struggle at the bottom to precede such a change at the top may take another hundred years, “the cotton” being such an unlikely weapon, but is it not preferable to making a revolution every 30 years or so and then being sent back to square one every time by the merciless hand of History?

Dear Alborz,

by Amir-Human Orfi on Fri Aug 14, 2009 08:39 AM PDTI would like to begin by addressing your "aspirin" example, that as clever as I think it is, does not apply to the situation here. Not the way I see the situation, at least. By invoking such a metaphor, you seem to insist on your previous position that religious persecutions and religious harassment are QUALITATIVELY different animals and should be dealt with separately and using distinct methods.

What I have tried to accomplish by writing on "eeza ye dini", is the clarification of the opposite of this point of view, in the sense that I see these as just different instances of one single phenomenon, i.e. "eeza ye dini", notwithstanding their varying degrees of intensity. To me, at this point, this is very much like recognizing a wide range of acts as 'theft', and then acknowledging that although theft takes very many shapes and various forms, theft qua theft remains unethical (and deserves punishment by law) no matter how big or small the act of thievery might have been. To me, "eeza ye dini" has a similar status, and as such should be rejected categorically.

So I respectfully remain unconvinced about the applicability of your "aspirin" example.

More on your recent post in my post below (or I guess above!)...

Approach is key...

by alborz on Thu Aug 13, 2009 10:35 PM PDT... to any transformation. I by no means advocate establishing one group as the 'biggest victims', however, if the approach fails to acknowledge and then address the range of "eeza ye dini", to use your term, then one must question the approach.

Transforming Islam, Islamic governance, and governance in Iran are all separate and distinct from one another. In fact I would go so far as saying that transforming Islam whould not be the objective of any reform, as it implies a transmutation into yet another sect amongst many that currently exist. Past history has shown that fractionalization in religion has only led to further violations of human rights of those that are in the minority (eg. the Sufi order in Iran).

Transforming Islamic governance is also problematic. The current constitution of the IRI acknowledges the rights of its citizens and yet the institutions of governance readily violate with impunity the letter and intent of the constitution whenever any threat is perceived. In short, the 'velayat faghih' and other organs of governance, such as the 'basij', have and will continue to impose their views and doctrines on the masses. They are the most potent elements and I don't envision a compromise here as their position is based on an 'ideology' or way of thinking as a opposed to an 'ideal' or 'aarmaan'. They have and will continute to eliminate differences in thinking by any means available to them.

Therefore I only see hope in an Iran where governance is independent of Islam. Such governance or the method by which institutions govern, must, first and foremost, preserve the rights, security and freedoms of Iran's citizens irrespective of the groupings that have become the bane of our society. A multitude of imperfect examples of such forms of governance exist and Iran can too have its own.

I completely appreciate the angle by which you are approaching this subject and I remain eager in learning of your thoughts in this regard. At the same, I hope that our discussion will aid in the evolution of your thesis to acknowledge the realities in Iran. It is my belief that religiously inspired persecutions are an extension of harassment but addressing them completely different approaches. Just as an aspirin may cure a headache, 10 aspirins will not cure a tumor induced migrane. The remedy needs to be more comprehensive.

Until later, best wishes,

Alborz

P.S.

by Amir-Human Orfi on Thu Aug 13, 2009 04:46 AM PDTTo Alborz:

Or think of it this way, if you're not yet convinced of my proposed approach:

If instead of trying to establish who or what group of Iranians have been the biggest victims of "eeza ye dini" (which I take it to be a more inclusive notion than just religious harassment in its usual sense), we categorically reject ALL variations of "eeza ye dini" as inhuman and immoral, then one can make good use of the following a forteriori argument:

When we consider even rather minor cases of harassing inhuman and immoral (if not yet illegal), then how can we tolerate the heinous crimes that have been so systematically perpetrated and are the harsher instances of "eeza ye dini"?

Wouldn't that help more?

Dear Alborz,

by Amir-Human Orfi on Wed Aug 12, 2009 07:42 PM PDTI now see how strongly you feel about the plight of Baha'is in Iran, and I can sympathize with you. Once again, by using the word "harassment" instead of "religiously inspired and sanctioned mistreatment of outsiders", I did not intend to imply that the atrocities that have been done in the name of religion have been but a mere harassment. I admit that I should have been more conscious of my readers' sensitivities and used more caution in choosing my words. I have already written another post in this blog, explaining the meaning of RH the way I use the term.

Now let's move from our dispute on terminology to a discussion of methodology. With all due respect, I do not believe that singling out a specific group and stressing their suffering, no matter how horrendous, will necessarily help them regain their civil rights more than viewing their pain as an instance of a larger injustice, shared by many others who do not belong to that specific group. Don't you think?!

The pleasure is all mine, sir.

More on definitions...

by alborz on Wed Aug 12, 2009 04:49 PM PDTDear Mr. Orfi,

Thank you for further elaborating on your choice of 'harassment'. While 'harassment' includes 'be sotooh avari', 'aziyat', and 'azaar', it does not extent to the realm of 'zajr' and 'shekanjeh', and which 'persecution' does. Furthermore, Iran's largest religious minority has faced an 'religiously inspired and sanctioned treatement' that has included summary executions, arbitrary imprisonments, and deprivation from any civil rights. The collective acts can be best described as 'ekhtenaagh' or 'strangulation' with the intent to eliminate the viability of this community. In the early years after the 1979 Revolution, the execution of their members was at a such a level that the word 'pogrom', which was first used to describe the extermination of Jew, could be accurately used.

As you can see the attempt to combine the entire range of religiously inspired and endorsed acts 'under the umbrella' of harassment will not do justice to the realities that you no doubt wish to acknowledge. The transformation of a society that has lived with these attrocities for 30 years will occur more rapidly than anyone expects. The recent turmoil and crisis in Iran indicates that change will not occur 'linearly' but rather 'non-linearly'.

Iran can go through one of three paths with varying degress of probability. These, in my opinion, are 1) Coup d'etat, 2) Reform, or 3) Revolution. Each one of these will impact your hypothesis, but for now we will set this aside.

When I get a chance later I will respond to the 'chicken and egg' question. For now, it is a pleasure to engage in this discourse with you.

Alborz

Dear Ali P.

by Amir-Human Orfi on Wed Aug 12, 2009 04:05 AM PDTThank you very much for your clarification of the legal status of the "N-word".

Regards,

A-H Orfi

Dear Alborz:

by Amir-Human Orfi on Wed Aug 12, 2009 04:02 AM PDTThank you for your critical comments. I do not mind your “direct” commenting, as long as it is done with respect, but I thank you for warning me in advance.

First of all, I agree that this blog entry is not as comprehensive as I would have liked it to be. I have just added another entry that I invite you (and other interested readers) to take a look at:

//iranian.com/main/blog/amir-human-orfi/religious-harassment-v-non-religious-harassment

I have tried my best, however, given my limitations in the amount of time that I can spend on such “extra-curricular activities” as well as in my intellectual ability to be more comprehensive in the Persian version, even though I admit that that one too has come out quite dense and I’m afraid some of the points I have tried to make may not get across that easily.

About “definitions”, you are certainly right on the money. I have given a loose definition of “eeza ye dini” in the Persian version that may not satisfy the more critical readers. I have tried to make up for the shortcomings of that definition by providing a few examples, and I hope to either have the opportunity to classify various forms of this practice myself, or others find the subject interesting and important enough to pursue such an endeavor.

I agree with you that “eeza ye dini” is not quite the same as “religious harassment”. This was pointed out before by another reader and I have since made a point of putting the English term in quotes. As you have correctly said, “eeza ye dini” is more general than a mere harassment and may envelope acts of religious persecution as well. I have chosen to define “eeza ye dini” in such a way to enable me to place all instances of religious harassment and religious persecutions and pogroms under one umbrella, because I believe they all originate from the same source, although they vary in their intensity. So by no means, did I mean to belittle persecutions by calling them “harassment”, if that’s your concern.

I appreciate your careful attention to what words mean and what words should be used, but frankly, I did not find in Persian any word more appropriate than “eeza” (that, I admit, is originally Arabic) for my purpose, that is, elaborating on a phenomenon that I saw as the root of so many evils in our society. So, if “eeza” means something else in your book, then I invite you to come up with a better Persian word to denote the notion I have been trying to get across with. In any case, in this particular instance, I don’t think what harm might have been done by choosing the word “eeza”, if you excuse the pun.

You wrote:

“While we can agree that Islam cannot be uprooted from Iran, it is the establishment of a civil society that can guard against it being used as instrument for a wide range of persecutions.”

As I wrote in response to Ali P., I see this as a chicken and egg kind of problem. (well, I didn’t use these exact same words there.) The question is whether we shall wait for the establishment of a civil society in Iran and hope to reap the fruits of living in such a society, or start right now, by attacking what makes Iranian society so un-civil, at least on the intellectual and educational front and then expect that to lead us to a more civil mentality and eventually the realization of a civil society in Iran.

Dear Mr. Orfi

by Ali P. on Tue Aug 11, 2009 11:24 PM PDTThanks for your comment. You asked:"Isn't use of the N-word in America somehow against the law?"

It is not.

Being a racist, bigot, or hatemonger, or hypocrite -fortunately, or unfortunately- per se, is not against the law in the US. You have a First Amendment right to use the N-word, or other common ugly words.

However, if you commit a crime, and during the crime you use that word, that may make your crime a hate crime, bumping up charges against you.

Yours,

Ali P.

A new definition for 'harassment' !

by alborz on Tue Aug 11, 2009 09:54 PM PDTMr. Orfi,

Please forgive my rather direct comment here as the topic is extremenly important and yet I find your blog as having missed the mark entirely on a number of fronts.

Definitions

Since when did the word 'harassment' take the place of 'persecution' and 'pogrom'?

The translation of the word (e-za) means 'maleficence' and 'harm' and not 'harassment'.

Your choice of the word 'harassment' leads to a number of questions which I will withhold until I have read Part 2.

Approach / Perspective

Rather than articulating principles that uphold the rights and perogatives of diverse communities in a society ultimately leads to its prosperity and fulfillment of its potential, you have approached the subject from the perspective of 'reform' . The problem with this approach can be illustrated with the example of women's dress code in Iran. When a woman is forced into complying with a dress code then relaxation of that dress code is not reform. When rights are removed, returning parts of it back is not reform.

I look forward to Part 2 of your article.

Alborz

It works both ways

by AK69 on Tue Aug 11, 2009 05:42 PM PDT-

As laymen to the conversation, and no knowledge of the full article, I simply add that much is historically and culturally influenced backlash for the Non-religious harassment received by the State’s institutional churches.QUOTE: It is then shown that one can easily approach the questions of justice, freedom, tolerance, etc. from this particular point of view, that is, via the concept of “religious harassment”.To that end, one can also look at it through the concept of historical “non-religious harassment’; can one not if one is to take all aspect into account for analysis?

AK69

Bar Labe Goore Man, Avaz Bekhan

I am glad to hear the

by Amir-Human Orfi on Tue Aug 11, 2009 05:35 PM PDTI am glad to hear the Persian version helped made it clear and also glad that you enjoyed it.

I completely agree that some milder forms of "religious harassment" will probably remain outside the domain of legislation. For example, you can't possibly expect the religious folks to smile at you or otherwise control their facial expressions when they see you do something un-Islamic, for example, hold your lover's hand in public. Bitterness cannot be cured by law, but verbal abuse may be controlled by law. (About your examples, isn't use of the N-word in America somehow against the law?)

I couldn't agree more with you that regime change will not necessarily bring about a sudden change in our collective behavior as a nation, although policies of the government may be conducive to forming certain cultural habits. But I'm not sure what you refer to as the "burial" of RH will have to wait until a secular regime comes to power. I believe RH in all its forms should be elaborated on and attacked by intellectuals of both religious and secular persuasions even before Iranians see the arrival of a secular government. In fact, fighting RH in the intellectual realm can be a first step towards a civil society, and not the other way around.

Thanks again for your kind words. I appreciate your feedback.

Dear Mr. Orfi

by Ali P. on Tue Aug 11, 2009 03:25 PM PDTThank you for your response. I just read the Persian version of your article and it made it all clear what you are trying to deliver. Point well taken.

The institutional 'religious harassment' will hopefully be buried in our country with a secular form of government, but there are always expressions of feelings- no matter how dumb, or hateful- that are, sadly, just out of the reach of the arm of the law.

(To your example of 'loud speakers', I could add the use of hateful -common- terms such as "joohood", or "gabr" for refering to other religious minorities)

That would not change with regime change. It changes when we all learn to view and respect each other as human beings; as members of a civil society.

I enjoyed your piece. Please write again.

Yours,

Ali P.

Example of "RH"

by Amir-Human Orfi on Tue Aug 11, 2009 02:49 PM PDTI forgot to answer Ali P.'s question:

"Could you give a better example of 'harrassment'?"

All right, how about loud speakers that your religious neighbor has installed in his yard for Muharram, broadcasting the story of Imam Hossein and his friends and relatives right into your ears, as told by the local mullah and all the cryings and wailings that you would not want to be a part of? How's that for "religious harassment" in an Islamic (Shi'a) society?

Dear Ali P.

by Amir-Human Orfi on Tue Aug 11, 2009 01:11 PM PDTThanks for your question. I agree that some people may not care that much about being "of the same color", as the Persian saying goes, as the people around them. You are also right that there may be no ACTIVE harassment, in the English sense of the word, going on in your examples.

Two things:

First of all, I have to admit that the notion I had in mind when I wrote that piece (the Persian version) was not exactly "religious harassment" in the Western sense of the word. That's why I mentioned in my reply to Mr. Ghiassi, "a broad sense of the word". So even though no real harassment is taking place, there is a tension that I suspect is caused by a fear of being harassed. Call it "potential harassment", if you will.

Second, I gave extreme examples from the opposite ends of the spectrum of "religious harassment" (and I am going to use quotes around this term more often from now on) and the example of feeling uneasy and perhaps even threatened by the religious fanatics was at the very mild end of the spectrum. True, no one is harassing anyone in your scenarios, but the tension in the air may be due to other forms of "religious harassment" having been already established in society.

Please read the Persian version. I hope despite its brevity it is more clear than the even briefer English version above. Think of this concept in a more "philosophical" sense, if that makes any sense. I have come to believe that this is a very general phenomenon in our society that manifests itself in a myriad of ways, but the essence of it is one and the same. If you're not convined after reading the Persian piece, please let me know and we shall continue this debate. I do welcome all well-argued criticisms.

I am not clear

by Ali P. on Tue Aug 11, 2009 03:28 PM PDTWhen you are the only bee-hejab in a religious setting, and everyone else is baa-hejaab, you may feel uncomfortable. Some do, some don't.

When you are the only baa-hejaab in a non-religious setting, and everyone else is bee-hejaab, you may feel uncomfortable. So do, some don't.

(In the above examples, we assume you are a woman!)

Who is harassing whom?

Could you give a better example of 'harassment'?

Dear Mr Ghiassi

by Amir-Human Orfi on Tue Aug 11, 2009 11:12 AM PDTYou may be right that some people use religion, among many other things, to "get rich and powerful", and some other people would have been better off if there were no religion at all to begin with. But I do not see how it is relevant to what I am trying to say here, that is, the fact that religious harassment, in a broad sense of the word, and the tendency to inflict pain on others because they do not believe in the mainstream religion or sect or do not act as if they did believe, is responsible for quite a lot of problems in our society. In other words, I think, and I hope justifiably so, that I have identified a main source of a lot of unpleasant issues that are prevalent in Iranian society. For example, the tension that you must have felt when you are in one place with a bunch of hezbollahis and you happen to look too clean-shaven, or your wife's scarf is loose, is, to me, reason to believe that religious harassment has been sanctified by the regime. Take this small example and go all the way to more explicit instances of religious harassment, such as depriving a bunch of dervishes from their place of worship, or expelling a student from the university because she is not considered "religious" enough, or follows another religion.

I hope what I was trying to say is more clear now.

Dear Homan

by Amir Sahameddin Ghiassi on Tue Aug 11, 2009 08:26 AM PDTSome people have nice life by religion and get rich and powerful, and the other people lose everything they have because of religions. It a good business for some and bad for the others. Amir