By Sheila Kamerman and Marieke van Twillert, published in NRC Handelsblad, Rotterdam, September 12, 2007.

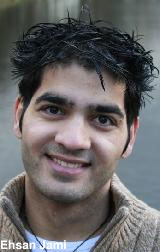

Why do so few Moroccans, Turks, Muslims from Surinam make themselves heard? Where are the Iraqis, the Afghans? In the current debate on Islam in the Netherlands, Iranians dominate. This became especially obvious when the discussion was given fresh impetus by the apostate Muslim, Ehsan Jami—of Iranian background.

Yesterday, Jami presented his Committee of Ex-Muslims. The only other member is Damon Golriz, a representative of the VVD, the Dutch liberal [conservative] party, and professor of mechanical engineering at a technical college, whose chief adviser is columnist and university professor Afshin Ellian. Both are from Iran. Similar committees in England and France, which served as a template for Jami, were founded by Iranians as well.

The opposing opinion is expressed by a different group of Muslims, who think that Jami should tone down his harsh rhetoric. They, too, claim an Iranian background.

The background of these Iranians, most of whom entered Holland as political refugees beginning in the 1980s, explains their assertiveness and visibility in the debate, says sociologist and publicist Shervin Niku’i, herself Iranian by birth. “They hail from the well educated middle class, from the large cities. They are familiar with Western values and culture. They form an elite group.”

“I have yet to come across the first non-ambitious Iranian,” says Farah Karimi, ex-parliamentarian for “Groen Links,” the Dutch Green Party. “This competitive streak has its origins in the way Iranians perceive education. Education is very important. All parents want their kids to study hard; boys and girls. You don’t have to be rich, as long as you are well educated.”

Iranian children are raised on the idea that you can make it yourself in life, says Navid Otaredian, an engineer from Delft who came to Holland 22 years ago “You are not handicapped by anything; you have and are nothing less than anyone else. What you achieve in life is of your own making.”

Well educated Iranians have found their entry into all areas of study and work in Holland, Niku’i says. “They are prominent in the political debate, but there are also Iranians among university professors, as there are engineers, businessmen, and physicians. They compare well with former refugees, often students, from Hungary and what used to be Czechoslovakia. They, too, generally did well. They represented relatively small groups, like the approximately 30,000 Iranians who now live in Holland. Compare that to the Turks (364,000), or the Moroccans (323,000). As Niku’i explains, “Most of the Moroccans and Turks who arrived in Holland in the 1960s were uneducated or poorly educated, and they came to do manual labor. It is hardly surprising that the most prominent participants in the debate have not emerged from their ranks.”

Besides the general educational level, the political context of the country from which they came plays an important role as well. Elian was an active communist before escaping from Iran; ex-parliamentarian Karimi belonged to the armed Mujahedin-e Khalq during the Revolution. Iran has a tradition of intellectual resistance against state power. Iranians living in the diaspora exhibit an acute political awareness.

That, Ghoraishi claims, is true for the generation which lived through the Revolution. But it also applies to their children, who grew up in that political climate. “Not that many people experience a revolution. But if and when you go through one, you learn. Make sure that you are heard. Engage in debate. Your voice counts!”

In Morocco and Turkey there is no political Islam, submits Behnam Ta’ibi, one of those who took the initiative to counter the “Islam-bashing” of Ehsan Jami. “In those countries state and religion are separate; Islam is far less of an issue. In Iran, politics and religion are totally intertwined. Islam is an imposed faith. When Turks or Moroccans living in Holland openly turn away from the faith, they are banned from the family.”

Striking is also the large difference in opinion about how to deal with those who think differently inside the Iranians diaspora, says Goraishi. Although Iranian in Holland are mostly left-leaning, they do not manifest themselves as one group, she insists. Ehsan Jami, his committee and the criticism it has elicited are good examples of that. “Some say, ‘We have experienced the danger of Islam from close up; we should battle this region anywhere in the world.’ And there are those who, affected by the freedom in their new homeland, distance themselves from extreme viewpoints, convinced that those who think differently, including Islamists, should have the opportunity to express themselves.”

Most Iranians in Holland share the existing rage about the Islamic Republic, Ta’ibi thinks. “Therein lie the roots of their commitment,” he argues. “But there is a difference in reaction. Some Iranians struggle against Muslims as if they are still in Iran. Yet, we do not live in Iran; we live in Holland.”

It is not just the presence of Iranians in the Islam debate that is striking; it is also the way of debating. “They never agree with each other,” says Loes Bijnen, until late 2004 attached to the Dutch embassy in Tehran for five years, during which time she worked on human rights. It irks her when nothing is achieved at large human rights conferences. “In no time things fall apart.” And “They talk, and talk and talk. At the end of a sentence they no longer know how they started it.”

Iranian tend toward a theatrical, bombastic way of speaking, using flowery language leavened with citations from the great Persian poets, Bijnen says.

Their debating style is polemical, Ghoraishi observes. “The approach is, ‘I am going to lay out my views,’ not, ‘I am going to meet my opponent somewhere halfway.’ It is very different from the Dutch way, which is consensus-oriented, in search of a middle ground.”

Navid Otaredian has a different view. The engineer from Delft doesn’t find the approach of Ehsan Jami and Afshin Ellian “constructive.” “This is not the style favored by our culture,” he argues. “The essence of existence is trying to enrich your life and that of others. You have to keep trying to understand your opponent, to search for other people’s motives. That’s why it is so odd that they present themselves in such a manner.” Philosophizing is every Iranian’s pastime, Otaredian insists. “We discuss poems at parties. Iranians are not just engaged with daily life, but also with its larger questions and with political problems.”

Professor Rudi Matthee is Distinguished Professor of Middle East History at the University of Delaware, and, most recently, the author of The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian history, 1500-1900 (2005).