This email has been making the rounds and I just received about an hour or so from a friend of mine. Check your inbox, you may well have received it yourself, as emails seem to circulate the now global Iranian community at light speed. The forwarded email in question is rather quaintly entitled Norooz for Reza and Mahmoud. Before I continue I wish to stress that this little essay isn’t intended as a polemic or diatribe against any of the parties involved. I merely desire to say that the email as a sort of cultural artifact, if I may call it that, strikes me as problematic for a number of reasons.

In the first photo we find the Pahlavi women and children unveiled, made-up and for the most part indistinguishable, from many other emancipated women you’re likely to come by in the western world. Reza sports an impeccable suit, crisp tie and is of course clean shaven. The family is happy and all appears well. Let me just unequivocally state that I am not for one moment or in the slightest criticizing or taking issue with any of this, Please make sure you take heed of this qualification before launching into hateful and bilious insults.

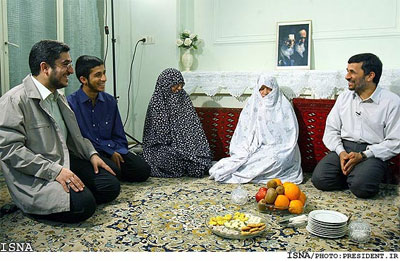

Pasted below the picture of the Pahlavis is Norooz at the Ahamdinejad home. The woman can hardly be espied as they remain ensconced within their all-encompassing chadors. Rather than all the modern trappings of a fine dining table and silverware, in traditional fashion they kneel and squat in a small circle on their no doubt finely woven Persian rug. Ahmadinejad and his two sons all have facial hair which has clearly been left unattended for several days.

Firstly, implicit within the ideological mise-en-scene, made all the more palpable by the juxtaposition of the two photos, is the fairly prevalent attitude amongst the Iranian middle class and some of the diaspora which goes something like this: ‘hey, take a look at these dāhātihā, one of whom is our laughable joke of a president’. The comparison with the model secular family as exemplified by the Pahlavis is surely supposed to elicit such a reaction, or something thereabouts. Many will continue I’m sure: ‘Look what we had, and look what we’re stuck with today!’ Such reactions are certainly on some level understandable and legitimate from the point of view of those espousing them; my only intent here is to try and problematize some of the unfortunate assumptions and preconceptions that underpin such a reaction, how the set up is clearly value-laden and a vehicle for a particular ideological position which has surreptitiously insinuated itself into the background against which we come to read the email.

Prima facie it’s fair to say that in the eyes of the sender and the audience for whom it was intended, the photo of the Pahlavis represents the virtues of ‘progress’ and ‘civilization’ while the photo of the Ahmadinejads is cast in the role of ‘backwardness’ and ‘crudity’. In this patently ideological figuration one fails to see that both at least on the surface of it, appear happy, jovial and content on what is after all a national celebration. Are we really qualified to impugn a family’s apparent happiness, even if it may well be a façade artfully crafted for public consumption?

The problem with a value-laden, ideological construct such as this is that its makers arguably on some level evince either a tad of self-loathing or a pointed denial of the fact that the ‘lifestyle’ of the Ahmadinejads, at least as presented in the photograph, is one which the vast majority of Iranians live and relate to. Though the populist politics of Ahmadinejad are at times highly objectionable and a mere cover for the IRI’s ongoing authoritarian governance, the denial that he has a constituency or that only the ‘clean-shaven’ middle-classes in either Iran or western capitals have a monopoly on Iranian identity, heritage, nationalism etcetera, is hugely short-sighted and terribly arrogant.

Rather than a straightforward religious-secular divide, the case of Ahmadinejad, unlike the ulema who have since the revolution emerged ‘fat cats’ and ‘captains of industry’, poses the more troubling question of class divisions and the considerable cultural, aesthetic and economic differences which separate Tehran’s variegated middle classes and those who continue to eke out their existence in the provinces and the shanty towns which line the outskirts of Iran’s metropolises. I’m not claiming that one group or section of society should take precedence at the expense of the other or that one’s demands is superior and should be implemented, while neglecting other people’s and groups’ claims. To put it somewhat superficially, there’s no reason why greater freedom of expression and association should be incompatible with an alleviation of the endemic poverty and destitution plaguing many families within the provinces as a result of rapid urbanization and urban migration.

Ignoring and systematically undermining the desires and demands of Iran’s middle classes obviously has had devastating repercussions for the country. The corollaries of Iran’s brain drain, the abuse of fundamental human and civil rights, gender discrimination, as well as a host of other debilitating afflictions of this kind, are felt on a daily basis and will continue into the future to severely damage Iran’s economic and social standing in the region and on the international stage. [1]

My main concern here however, is with the implicit repudiation of the Ahmadinejads as dāhātihā. In this instance, I’m not interested in the man and the crimes he may or may have not committed. It’s the snobbery and disdain toward a sizeable section of kind, good-humored and gentle people who make up the overwhelming majority of the Iranian people and who continue to live in similarly humble and unassuming circumstances. Such snobbery, derision, or maybe just benign misunderstanding, acts not only as a gross insult to millions of Iranians, but in my view is a shameful preponderance of the gaping chasm that later became evident between the late Shah’s image of his relationship to the Iranian people and the stark reality of that relationship, which ended in revolt and hatred.

Not only is such disdain problematic but belies the fact that ‘Iran’ has managed to exist in multiple guises and imaginaries for multiple individuals, political and social groups, classes, ethnic and religious groups. Persian ethnocentrism and the exaltation of our Archimedean imperial past has as much claim to speak for ‘Iran’ and ‘Iranians’ as the religious nationalism of individuals such as Ahmadinejad, and vice versa. There are of course many other images, associations and identities with a legitimate claim to define and speak about our heritage and history and whom are rightfully entitled to articulate their vision of Iran as a nation and a people: Jews, urban secularists, Baluchis, religious peasantry, Kurds, Shi’ites, women, Sunnis, secular peasantry, religious bazaaris, Zoroastrians, Azeris, Bahais, Arabs and Armenians etc…

From this it’s clear than no political faction, class, gender, ethnicity etcetera has an unassailable monopoly on ‘Iranian-ness’ and the plethora of meanings that a rich heritage affords. It is exactly because Iranian history is so vast and hotly contested that no single individual or entity can claim to speak for it in its entirety. All of the aforesaid groups and many others have played a part in our national evolution and the development of a multi-faceted, plurivocal and dynamic cultural consciousness. All of which have and continue to contribute in some way or another to the tributary of how we interpret ourselves and the world within we dwell and co-exist.

[1] I am not saying the issues of gender and civil rights are solely the concern of the middle classes; that’s patently untrue. The fact remains however that the prime objective of Iran’s underclass is the betterment of its economic standing and standard of living as opposed to the lofty rhetoric of ‘a dialogue of civilizations’.